Early last month I reread, not for the first time, Lorrie Moore's short story “People Like That Are the Only People Here,” first published in the New Yorker almost 30 years ago. It's about a mother who receives the terrible news that her 1-year-old son has cancer.

One passage seemed to me like a missive from the universe.

The mother, Moore wrote, now lives “by the jokes: Take one day at a time. Adopt a positive attitude. Go for a walk! I wish there were more interesting things that were useful and true, but now it seems like only the boring things are useful and true. One day at a time. AND At least we have our health.. How normal. How obvious. One day at a time: do you need a brain for that?

As it happens, I'm learning that it takes a brain for that.

For the past few years I have been helping to take care of my parents. I thought the experience might teach me something about how to die, but instead it is teaching me how to live.

My parents are in New York, where they have home care. I fly back not infrequently to visit and attend to necessary matters. I accompany them to doctor visits and make sure bills are paid.

If you had told me when I was younger that this would be what I was doing, I would have shook my head.

Back then, I wanted nothing more than distance, an escape from the familiar. She was looking for a way to get around “the nonsense,” looking for anything that couldn't be encompassed in a slogan or a cliché.

However, what I have discovered in caring for my parents is what I have come to imagine as the wisdom of the everyday. What is the right next step, the task that needs to be done? What should I do to keep them healthy and safe?

The truth, of course, is that I have no control over any of this, which is where the bromides come into play. The only option available is to remain flexible and present, to respond to each situation as it occurs. One day at a time.

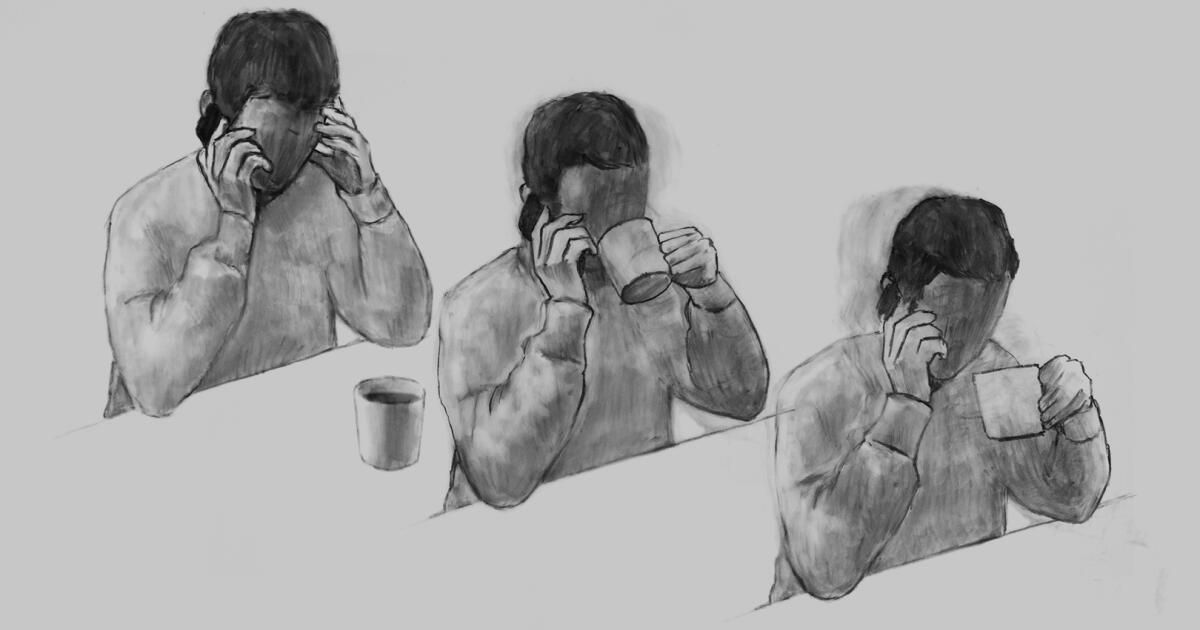

Last week, while having my first cup of coffee in Los Angeles, I received a phone call from New York. My father was dizzy and couldn't stand up. I spoke with a nurse from his primary care provider; she recommended a visit to the emergency room. Thus began a day of unforeseen challenges: finding an ambulance, consulting with her doctors, and organizing overnight care for when she was discharged. There was no other option but to do it.

I have a friend who likes to say that experience is neutral, that what matters is how we react. Over the years, I have approvingly repeated that phrase and others like it: “Be here now.” “It is what it is.” – without even fully acknowledging what they meant. I understood them intellectually but not emotionally; They existed for me as ideas, although not (not yet) as necessary strategies.

Now, like the mother in Moore's story, I have felt honored. Even as part of me continues to resist, I have acceded to the demands of the narrative.

Among the particular consolations of literature is the solidarity it can provide: not that we are not alone, because we are, but that others have experienced similar events. For me, the stature of a piece of writing is measured by what it offers in repeated encounters, how it reflects or amplifies what we are going through.

I have taught several times “People like that are the only people here.” I've written about it and about Moore too. But before I had not paid much attention to that passage because I was not yet ready to see it, to hear it. The central question: how do we learn to stay in the moment, without expectations? – it didn't belong to me.

That's all changed, of course, I appreciate the lesson. In other words, I find comfort in equanimity, regardless of what comes.

For now, my parents are safe at home. As for what happens next, we'll deal with that when it comes. One day at a time. The experience is neutral. Be here now. It is what it is.

Bromides? Yes. How normal. How obvious. And yet, it turns out, that is precisely what is needed.

David L. Ulin is a contributing writer for Opinion.