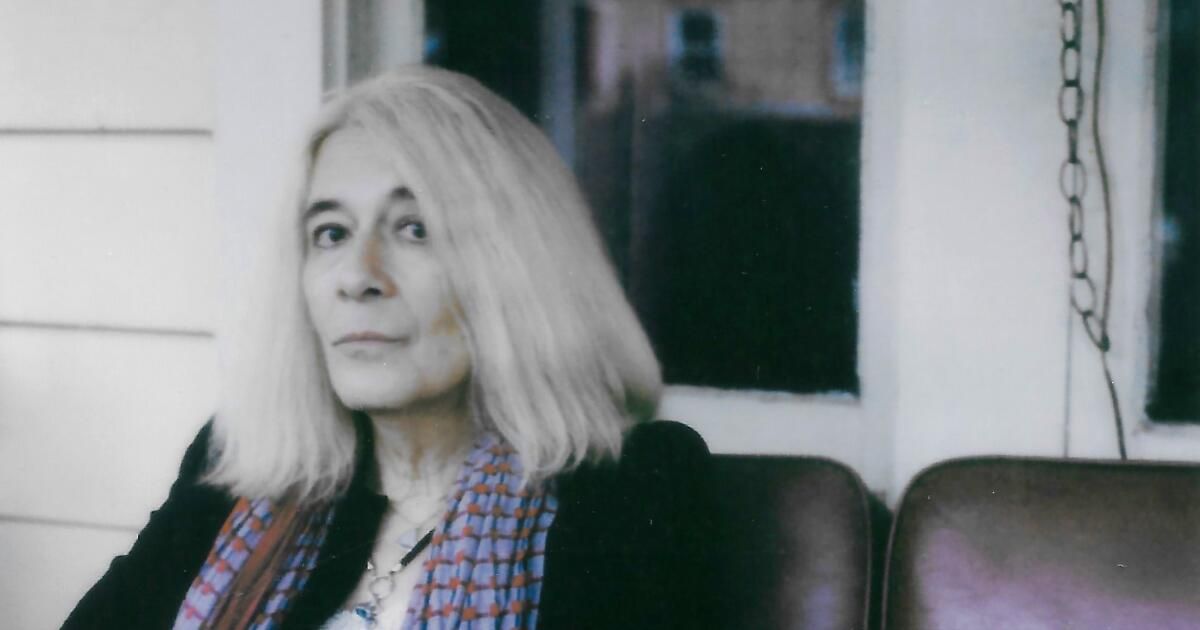

Book Review

I heard her say my name

By Lucy Santé

Penguin Press: 240 pages, $27

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from bookstore.orgwhose fees support independent bookstores.

For 66 years before her decision to transition from male to female, Lucy Sante existed in a “prison of denial,” alternating between vague restlessness and deep discontent. What was the root of this? Nearly four decades of therapy had produced no response. But as she recounts in her fascinating memoir, “I Heard Her Call My Name,” “the transition eliminated my neuroses and left me, in Freud's words, with ordinary human unhappiness.”

Throughout Sante's life, there were flashes of a desire to become a woman, but she had never delved into whether there might be a deeper meaning to these impulses, even as they consumed her. She remembers that when she was 11 she sneakily tried on her underwear and her mother's dress, then her eyes widened and her mouth softened, like she thought a little girl would do. she fantasized about playing a female role in a play or becoming the protégé of a wealthy socialite who would dress her like a doll. These daydreams persisted throughout adolescence and adulthood; but when they surfaced, Sante pushed them down, focusing on manhood, marrying twice, “trying to push any lingering gender issues to the bottom of the stairs, where no one, including me, would ever see them again.”

Then in 2020, Sante tentatively tested a gender-swapping feature on FaceApp to conjure up an idea of what she would look like as a woman. “She was me,” Sante writes. “When I saw her I felt like something liquefied in the center of my body… Finally she had fulfilled my reckoning.”

Soon she was “entering every portrait, snapshot, and ID photo I owned of myself into the magical portal of the genre,” including images of herself as a teenager. “That could have been me,” she remembers thinking. “Fifty years underwater and she would never get them back.” She excitedly shares the news that she is transitioning and explains her “origin story” with her close circle of friends, including his lifelong companion, Mimi. Most supported him, although Mimi concludes that this would mean the end of their romantic relationship. But “the dam had burst. …Now that I have opened Pandora’s box,” Sante writes, “I cannot close it again.”

“I heard her say my name.” It is a memory without a conventional beginning, middle and end. Sante, who studied at a Jesuit school for boys At school in Manhattan before being “sent down,” I learned “how to stand trial and simultaneously serve as prosecutor, defense attorney, judge, jury, bailiff, and a host of witnesses for and against.” He is relentless in his self-interrogation. No period of his life is exempt from the pricks and pricks of it; There are frequent shifts from current reflections to childhood episodes that could unlock an answer to Sante's perpetual question: Who I am? The author's approach is circuitous and there are never definitive answers. Had he been pretending to be a man? Was he too old to embark on this journey? Would she be seen as “pathetic” in a dress and a wig? Or, more pressing: “How is it possible that my 'egg' has 'broken' sixty-odd years after I knew about it?”

There is a brief pause in Sante's ambivalence as she experiences the “pink cloud” that accompanies various phases of her transition: immersing herself in trans literature and art; experiment with makeup and hair; shopping until she drops. She finds joy and liberation in letting go of her past: “It was a process of elimination” during which she “from time to time might feel strange,” but she no longer had “a shred of doubt.” She likes to “watch his masculinity dry” from her.

At times, accompanying Sante through the many U-turns and dead ends he takes the reader to can be exhausting: just as you think he's finding a solution, there's another caveat. However, it is impossible not to be moved and fascinated by Sante's exhilarating yet painful journey. He worries that the literary reputation he has built as Luc Sante, author of eight previous books, professor at Bard College, and longtime contributor to such prestigious publications as the New York Review of Books, will be eradicated by her change of identity. She grieves the loss of her relationship with Mimi, perhaps the love of her life. She worries that they will see her simply as a man in disguise, when what she wants is “to be a woman, not a satire.”

The final pages of “I Heard Her Call My Name” It finds Sante reflecting on the plight of trans people in the world and surprised that she herself finds herself comfortably among them. “I am the person I feared the most in my life,” she observes. “I was broken for a long time, but now, as mafia guys say, I'm back on my feet.”

Leigh Haber is a writer, editor, and editorial strategist. She is a former director of Oprah's Book Club and book editor of O, The Oprah Magazine.