The American industry has been receiving a lot of practical direction from Democrats and Republicans for quite some time. Every few years, someone looks at the disappointing results of these economic maneuvers and insists that a true “industrial policy” has never been attempted. The truth is that the left's call for a “mission-oriented” state and the right's yearning for a nationalist industrial resurgence may seem different, but they share the same presumption: that their own intentions may finally succeed where decades of intervention have failed.

The latest person to revive this enduring fantasy is Mariana Mazzucato, the Italian-born economist who has made a career of defending an assertive, big-spending state as an engine of innovation. In a new interview with Politico, he laments that President Trump's industrial policy, which includes tariffs and state stakes in private companies, is “an idiosyncratic hodgepodge“, not the “holistic” strategy she favors. Mazzucato wants the United States to have a “smart and capable” state to guide investment with purpose.

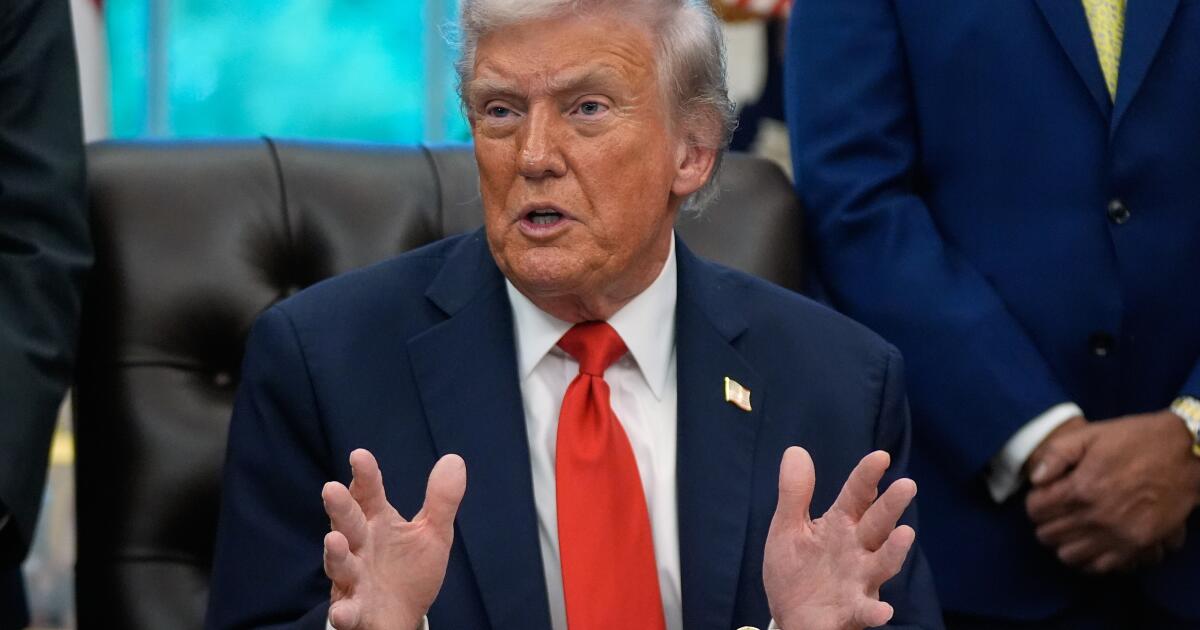

In the days of President Biden's industrial policy, when subsidies, tax credits and loans were flowing, an emerging Republican faction had a similar refrain, claiming that to revive American manufacturing, restore communities and put men back to work, you simply had to get industrial policy right. We now know that this meant increasingly erratic tariffs, price controls, and government takeovers of businesses.

The hope for both sides rests on an important premise: that Washington can direct trillions of dollars toward the right industries, produce a manufacturing boom and perhaps even heal America's social fabric.

The problem is not that industrial policy has been done badly. It's just bad economics.

Dreams of reviving manufacturing jobs face the reality that modern manufacturing is capital-intensive and largely automated. Even if government subsidies or loan guarantees stimulate a factory boom (and history suggests otherwise), they won't bring back 1950s-style armies of industrial workers unless we somehow outlaw productivity. Today's factories are powered by robots and engineers.

Tariffs will not bring about a revival of the manufacturing sector either. Taxing inputs and components only increases costs, weakens American competitiveness, and ultimately punishes the companies that protectionists claim to support. True American industrial strength is based on productivity, innovation, competition, and access to global supply chains, not coddling producers behind walls of higher prices.

Mazzucato and his ideological opposites make the same mistake. They imagine a technocracy free of politics that can “direct” the economy. In the real world, politics always dominates economics. Subsidies and tariffs are never experience-neutral tools; They are invitations to lobby. Every “strategic investment” quickly becomes a political promissory note.

Biden’s programs came loaded with child care mandates, union preferences, and “Buy American” rules. Trump’s industrial interventions are certainly erratic, but the idea that his protectionism would work if it were wrapped in a more “mission-oriented” narrative is even sillier. Industrial policy does not fail because it is chaotic, it fails because it is political, and human politicians are incapable of achieving the precision that markets achieve every day.

After sweeping review of five decades of US industrial policyThe conclusion of economists Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Euijin Jung was unequivocal: subsidies and trade protections for individual businesses have been politically irresistible but economically ruinous. Government protection delays economic adjustments; innovation succeeds. In the rare cases where industrial policy showed positive results, the government simply supported open, competitive research and innovation (programs like DARPA or Operation Warp Speed) rather than protecting companies from competition or subsidizing failing industries.

Without that kind of openness, supposed victories in industrial policy will quietly fix yesterday's technology instead of helping to unlock tomorrow's. France's Minitel, a government-backed precursor to the Internet, seemed like a national triumph in the 1980s. Millions of homes were connected, citizens used it to bank, shop and communicate, and the state could boast digital leadership. However, the system's centralized, permission-based design stifled innovation and prevented France from developing the open, global Internet that would soon transform the world.

The illusion of progress turned out to be technological stagnation: a product that barely evolved over three decades. This is the invisible cost of industrial policy. By isolating favored industries and technologies, it freezes innovation and leaves a nation paying twice: once through taxes and once through lost opportunities.

So yes, real Industrial policy has been tested, in many countries, by governments of all ideologies, under all rhetorical slogans, from “innovation” to “resilience”. It always fails for the same reason: the visible hand of the government is clumsy, interested and easy to buy. If that's what counts as a “smart state,” I'll take the invisible hand of the market any day.

Rugy Veronica He is a senior fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. This article was produced in collaboration with Creators Syndicate.