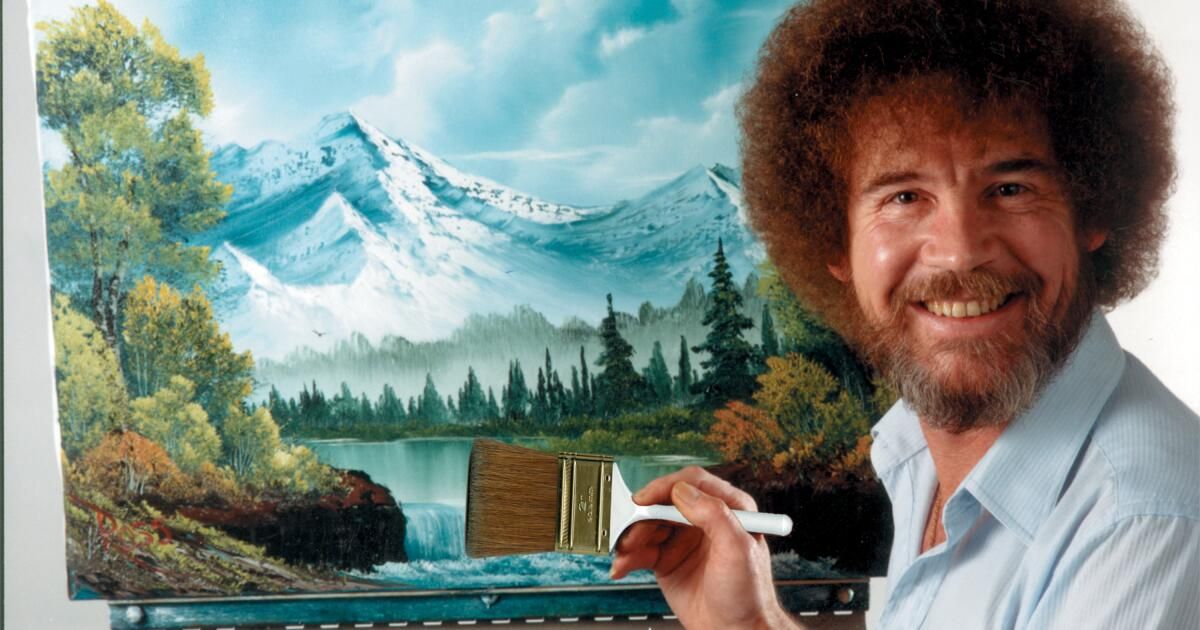

The indomitably indulgent painter Bob Ross, who assured us that mistakes are simply “happy accidents,” didn't usually talk about politics. But it's worth remembering when he turned to the experts to draw a wandering evergreen: “That's a crooked tree,” he joked. “We'll send it to Washington.”

The Crooked Trees of DC took the unusual step this summer of recouping funds they had already approved for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which closed its doors on September 30, putting public radio and television stations across the country in dire straits. The works of the late Bob Ross, a former Air Force drill sergeant who continues to delight PBS viewers around the world with “The pleasure of painting” Now it will go to auction to benefit public media. The first three of 30 paintings Bids will be presented in Los Angeles on Tuesday.

It's a brilliant and generous move by Bob Ross Inc., and one that shouldn't have to happen. While Bob Ross' legacy will live on with or without CPB, the loss of public media is hitting small towns, rural areas, and indigenous peoples across the United States the hardest. These are the Americans for whom public media is a utility, serving as a vital source of information, emergency alerts, cultural programming and community identity.

It is up to all of us to save public media as a free, essential news service. We have the opportunity to reshape public media, improve its business with a sustainable model and ensure that this resource can continue to operate and serve the public. After more than a decade supporting public media, our family foundation is doing more during difficult times. We're asking other philanthropically-minded foundations, families and individuals, and anyone who grew up painting happy or even crooked little trees with Bob Ross, to join us.

Much has changed in the media landscape over the past 60 years, but the need for public media remains the same. The 1967 report that laid the foundation for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting put it simply: Public media “must consist in their very essence of vigorous and independent local stations, adequate in number and well equipped. They must reach all parts of the country. They must individually respond to the needs of local communities and collectively be strong enough to meet the needs of a national audience. Each must be a product of local initiative and local support.”

In a rare result in reporting, all of this actually happened. The network of public radio and television stations – created thanks to the philanthropically funded report, a forward-thinking bipartisan Congress and private sector support – has the power to reach more than 95% of Americans, using less than 0.01% of the federal budget, or less than $2 a year per household. Most stations relied on federal funding for small portions of their budgets, typically only 10% to 15%.

For that small sum, the stations offered free educational programming (from “Sesame Street” to “NOVA”) along with local journalism; weather and agricultural news; coverage of events, sports and culture; candidate debates; and outlines of figures throughout the ballots. These stations decrease polarization and drive volunteerism and voter participation in whatever county they are in, red or blue. Nine out of 10 rural public stations provide original local and on-the-ground reporting.

Public radio provides emergency information, including evacuation alerts, when extreme weather cuts off power or broadband, which is already spotty and expensive in many rural areas. Original reporting on issues like water access in West Virginia's Appalachian towns and invasive species gaining ground on Kansas farms wouldn't be heard without public radio, particularly given the precipitous decline of local journalism in recent decades. And indigenous communities would not have access to news in their native languages.

It's no surprise that public media remains one of the most trusted sources of news anywhere, even among conservative listeners and viewers, despite what national politicians may claim. Independent studies have found no evidence of consistent bias in public media reporting. And while individual stories may appear biased to listeners and viewers, public media investigates and addresses allegations of bias. If that work needs to be strengthened, that's fine, but in the meantime Congress has thrown the baby out with the bathwater.

Before the federal government waived its funding for public media, both public radio and television were already working to strengthen the essential local services they provide — efforts we can all support right now. Our foundation was an early funder of NPR's Collaborative Journalism Network five years ago to expand the capacity of smaller local stations through regional collectives that can conduct joint investigations, increase coverage of underserved communities, share news equipment, make local stories available to national audiences, and seek technological and other efficiencies.

The result has been expanded news coverage throughout the Midwest, Appalachia and the Mid-South, the Mountain West, the Gulf states, New England and California, on issues ranging from state-level politics to mental health care in nursing homes to the unaffordable costs of public services.

Indeed, public media has already responded strongly to the collapse of federal funding with renewed donation campaigns across various funding sources (the auction of Bob Ross paintings is expected to raise about $1 million) and commitments to rely more on shared services. If more of us pitch in, perhaps public media will not only save itself, but show us how to sustain sustainable local news and, with it, the connection, community and identity that are essential threads in the fabric of our country.

Wendy Schmidt is co-founder and president of the Schmidt Family Foundation. She and her husband, Eric, are long-time supporters of NPR.