History may not be repeated perfectly, but often rhyme. Two protectionist episodes, the infamous Smoot-Hawley Law of 1930 and the Trump era of today, offer a surprising example. Both came out of economic nostalgia and fear of change. Both were politically attractive. And both were expensive and backward mistakes that undermine the economies that were destined to protect.

Smoot-Hawley was conceived in a concern of the United States for economic transformation. In the 1920s, while the economy was booming, farmers were in crisis. After a postwar boom, crop prices collapsed and the rural debt shot. About a room From the workforce it still worked in agriculture, below half of a few decades before. Many Americans yearned for an earlier era when agriculture was dominant and prosperous.

Foreign competition was the scapegoat. Politicians seized this frustration. The promising protection of cheap imports was an easy way to gain votes. The result was a rate that increased duties in more than 20,000 goods by an average of approximately 20%.

Smoot-Hawley's intention was to reduce imports and increase national prices, especially for farmers. But the plan failed quickly. The US business partners retaliated such as Canada, Mexico, Cuba, Great Britain, France and others imposed their own tariffs. Exports collapsed, imports became more expensive and global economic conditions deteriorated.

The moment could not have been worse. The great depression had begun and the stock market, which had been slowly recovering from the 1929 accident, fell again when the bill became law. Instead of stabilizing, the United States sank more in depression. Far from rescuing American farmers, tariffs deepened their crisis. Between 1929 and 1934, global trade collapsed at 65%.

Today, Smoot-Hawley is widely considered as a catastrophic error.

Now fast towards the new wave of protectionist nostalgia, this time with the aim of restoring manufacturing. The Trump campaign in 2016 promised to relive the loss era of factory work and industrial force. And like the Republicans of the 1920s blaming foreign crops for the collapse of agriculture, Trump blamed imported manufactured goods.

It does not matter that the United States has long changed services based on services or that manufacturing represented only 10% of jobs for 2016. The emotional attraction of “making the United States again” was based on a mid -class wandering of nostalgia for the age of smokes and assembly lines, and a broad and homogeneous middle class, before globalization and automation transformed the economy.

When Trump assumed the position again in January, he inherited a robust economy that had improved even more after his choice, based on the anticipation of investors of pro growth policies. Instead, the administration turned to economic nationalism and shot the economy on the foot.

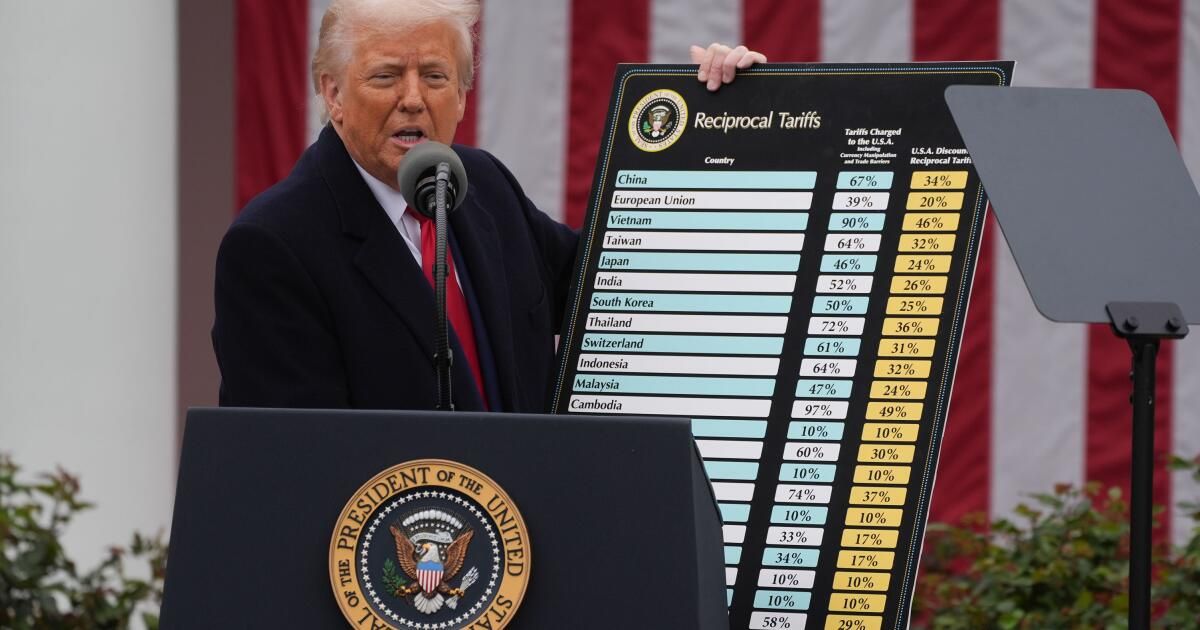

The culmination occurred on April 2, when Trump announced radical tariffs of the “day of release” of 10% in all additional imports and tariffs directed and directed against homologists such as China, Japan, Vietnam and the European Union. He launched it as a patriotic effort to restore sovereignty and reconstruction of the industry.

As we know, the consequences were immediate. The markets collapsed and the commercial partners threatened with reprisals, and some even took measures. Economists warned about the increase in costs, damaged supply chains and diplomatic tensions. Australia, among others, condemned the measure as economically hostile. The small businesses sued the administration, arguing that the tariffs exceeded the presidential authority and inflicted serious damage.

And just when Smoot-Hawley hurt the farmers, he was destined to help, Trump's tariffs are harming manufacturers. Far from delivering industrial renewal, they have led to layoffs in manufacturing plants.

In the end, despite its populist packaging, the day of liberation marked a dramatic escalation of failed protectionist thinking. He also revived the nationalist rhetoric in the style of the 1930s.

The two errors have one more thing in common: chrononism. According The economic historian Douglas A. Irwin, Smoot-Hawley was not mainly ideology. It was the policy of the interest group: an ad hoc struggle promoted by constituent demands, sector lobbying and legislative negotiation.

In the same way, Trump's tariffs have revived the lobbying for the exemptions of rates we saw in their first term. Apple has a exemption For the iPhone and now, understandably, everyone else wants one. Like the Lincicomo Scott of the Cato Institute commented In X, “the chrononism buffet line is now open.” Dominic Pino from National Review calculated This tariff lobbying has increased by 277%.

The lesson is clear: economic nostalgia is a bad guide for solid politics. Smoot-Hawley and Trump tariffs represent attempts to recreate a romantic past, one of small farms or bustling factories, instead of embracing the reality of a changing world. But economies are dynamic. Trying to freeze them instead with commercial barriers does not stop change; It simply makes the transition more difficult, more expensive and more painful.

History judged Smoot-Hawley hard. The final verdict on Trump's rates is not yet written, but the first signals are familiar. If we want prosperity, we must look forward, not backwards. The future belongs to those who embrace creative change and destruction, not those who resist.

Veronique de Rugy He is a senior research member at the Mercatus Center of the George Mason University. This article was produced in collaboration with the creators Syndicate.