On August 11, 1965, 60 years ago, I was paralyzed with hundreds of others in the corner several blocks from my house in South watching it what seemed like a horrible page of “Dante's Inferno”.

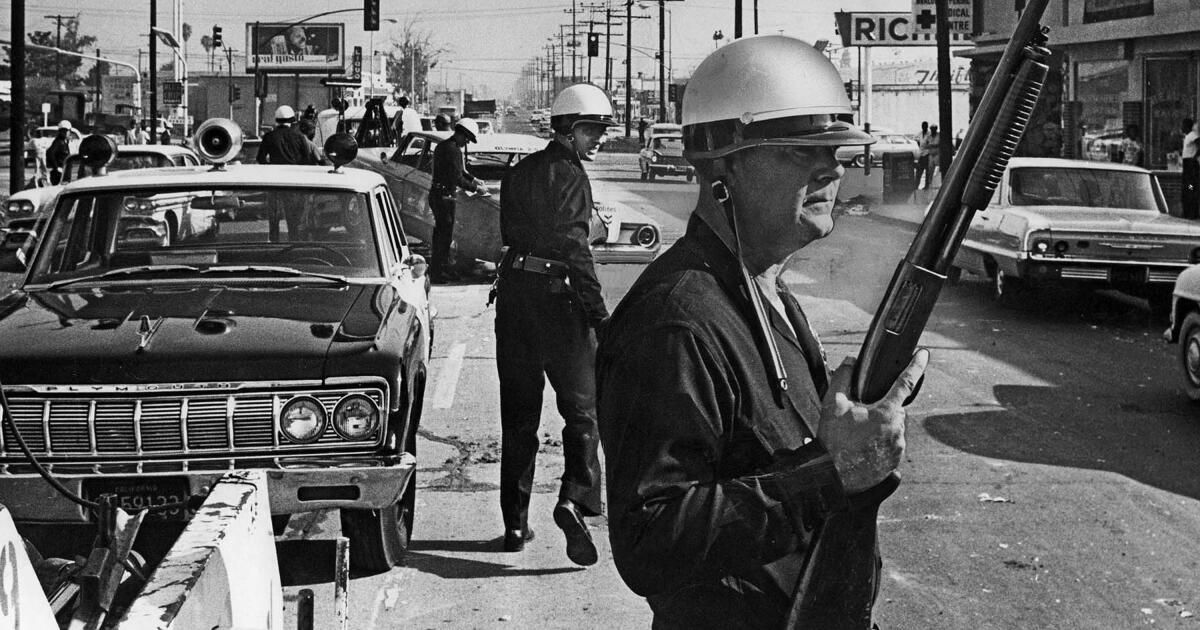

But this was real life. The liquor stores, a laundry and two dry cleaires moved away. There was a rumble in the ear of the screams, curses and teasing of the crowd in the police cars that accelerated with full battle team police, shotguns that leave their cars.

There was an almost carnival air of euphoria between the itinerant crowds such as packages of young people and not so young who threw themselves to the stores snatching and grabbing anything that would not be nailed. His arms covered with liquor bottles and cigarette cartons. I was 18 years old and felt a childish mixture of amazement and fascination to see this.

For a moment there was even the temptation to make my own career in one of the flame stores. But that happened quickly. One of my friends kept repeating with a contorted face of anger: “Maybe now see how rotten they treat us.” At that bitter moment, he said what without innumerable other black people felt when the flames and smoke swirled.

The events of those days and their words remain burned in my memory on the 60th anniversary of the Watts disturbances. I still think of the streets down that the Police and the National Guard embedded us during those infernal days.

They are impossible to forget for another reason. Exactly six decades later, some of those streets seem that time has stopped. They are splashed with the same fast food restaurants, beauty stores, liquor stores and groceries for mom and pop. The main street near the block in which I lived is so careless, full of potholes and garbage in the trash now as always. All houses and stores in the area are hermetically sealed with iron bars, security doors and anti -theft alarms.

When analyzing carefully what has changed in Watts, and all neighborhoods in the United States as Watts, since the disturbances, the image is not flattering. According to Data USA, Watts still has the highest poverty rate in Los Angeles County. Almost a third of households are well below the official poverty level. It has the highest unemployment rate. It is still full of the same shortage of retail stores, medical care services, chronically low educational test scores and high drop -out rates.

The almost frozen conditions in Watts were horribly punctuated in the long battle that residents and defense groups fought last year against city agencies to clean contaminated water that represented huge health and safety risks for thousands. It is a battle that is still getting rid.

Somehow, what I see in Watts is now worse than I remember before the riots. Despite grinding poverty among many in Watts six decades ago, almost all residents had refuge. The view of the people sleeping in the streets, in the bus stops and in the park was practically unimaginable in Watts in 1965. That is not the case today. The lack of housing, as in other parts of southern Los Angeles, is an important problem.

However, this is just a reference point of how little progress has been made since the riots in confronting racial evils and poverty in a watt still unattended.

Many black people in the six decades since the riots have long escaped such neighborhoods. Their lives, like mine, are now lived away from the corner of southern Los Angeles, where I was once in the middle of the flames and chaos. Its flight was possible thanks to the avalanche of civil rights laws and voting rights, state and local bars against discrimination, and the affirmative action programs that for many of them demolished the historical racial barriers of the nation. The Top Black Parade appointed and elected officials, including a former president, the legions of CEOs, athletes and legions of Black Mega Millionaire are evidence of that.

However, that does not alter the harsh reality that a new generation of black people now languishes in corners like the one in August 1965. For them there has been no escape.

But not everything is pessimism. There are defense groups such as Watts Rising that press city officials and the county of greater initiatives and financing programs in each area of life, including housing, jobs and income impulse programs, together with a large investment in better health services.

Another memorable moment for me during those hellish fire days was when Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. arrived at Watts at the height of the disturbances. He was mocked by some black residents when he tried to calm the situation. But King not only delivered a message of peace and non -violence; He also deplored police abuse and poverty in Watts. Sixty years later, it would surely have the same message if it came to the south of Los Angeles or any of the other similar neighborhoods in the United States. Very little has changed. Too much has worsened. What I see in those communities 60 years after Watts disturbances remain a great and worrying proof of that.

The last book by Earl Ofari Hutchinson is “Day 1 The Trump Reign”. Your comments can be found at Thehutchinsonreport.net.