On this July 4, with federal troops even in the field in Los Angeles, our own US revolution offers a surprising lesson about the dangers of military overreach in domestic affairs. In particular, the political and military leaders of the nation should consider the British errors of the 1770s while weighing the possibility of militarizing the US streets, now and in the future.

The Tax of the Law on Stamp of the Parliament of the mid -1760s lit the Anglo -American conflict. However, as historians are widely agreeing, martial law in Boston was increasing under different legislation, the coercive acts of 1774, which transformed US resistance into a large -scale revolution.

Let's start by remembering what had happened four years before during the protests of Townshend's duties, a series of taxes that Parliament added to everyday goods, including tea, exported to the colonies. The British ministry responded to the riots parking approximately 2,000 red coats in Boston.

On the night of March 5, 1770, in an accidental bloodbath he left for the fighter of soldiers with snowballs, the British opened fire against a multitude of unarmed civilians outside the customs, killing five and hurting others.

“Let me observe“, Sam Adams soon wrote about Boston's massacre,” how fatal the effects are, the danger of the one I mentioned a long time to publish a permanent army among free people. “

The problem worsened after the Boston Tea Party. The piracy of 342 tea boxes owned by EAST India Co. at the end of 1773 was, of course, criminal activity. As such, he justified the complete application of the colonial and municipal law against criminals.

However, instead of leaving justice to the locals, Parliament approved the four draconian bills known as coercive acts. To enforce them, in a fatal progression, King Jorge III's ministers sent a military governor and occupied the army to Boston, in effect imposing martial law throughout the colony for the illegal actions of a few.

Each of the coercive acts hit the heart of the Massachusetts autogobnose. The Boston port law closed all the trade through the port of Boston and its surrounding river routes, while the Massachusetts government law dissolved the assembly of the colony, the courts and meetings of the city. The remaining two acts allowed the judgments to be relocated abroad and forced residents to house British troops at the discretion of the governor.

Together, coercive acts constituted an assault unprecedented to the rights and freedoms of the US people. The settlers denounced them as “barbarian“Diabolic” and “tyrannical”: the work of a “despotic power.”

What followed is familiar to many Americans. Massachusetts, under martial law, summoned the other colonies to a continental congress in Philadelphia. In reaction, the king and the Parliament declared that the colonies were in a state of rebellion, ordering thousands of additional red coats through the Atlantic to crush the dissent and make arrests.

A conflict that the British thought they could solve with boots on the ground only intensified. On April 19, 1775, in another tragedy of involuntary butcher shop, this time caused by a lost bullet, the king's troops fired eight colonials in Lexington Green, turning the protest into the civil war.

Fifteen months later, as a remedy of the last resort, the colonies declared independence, highlighting the regime of the Martial Law of Great Britain as the first cause of the violation. The statement barely accuses King Jorge “abolish our most valuable laws“” Suspend our own legislatures “and”[keeping] Among us, in peace times, permanent armies, without the consent of our legislatures. “

History does not deliver road maps, but abounds in examples of military overreach that cause unpredictable violence. In the case of the American revolution, we are reminded that deploying an army in the streets where citizens of one live and work causes tension, fear and anger, and sometimes by the twin forces of accidents and climbing, bloodshed and lasting civil discord.

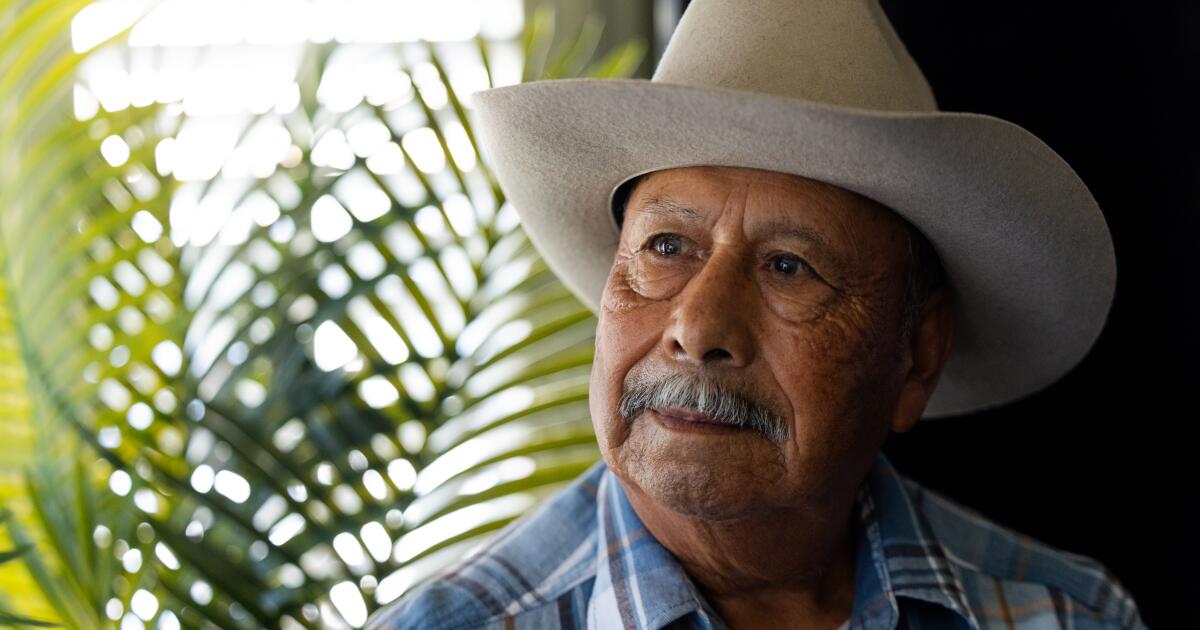

Eli Merritt is a political historian at the University of Vanderbilt. He writes Subsistence bulletin Commonwealth American and is the author of “disunity between us: the dangerous policy of the American revolution.”