An El Dorado County Superior Court judge on Friday formally exonerated a deceased Oregon woman who had falsely confessed to committing a brutal murder in the Sierra Nevada foothills decades ago, ending the life of her two adult sons who were children when she was imprisoned for a crime she did not commit.

“The public often thinks that a prosecutor’s job is to do nothing but go in and try to lock people up,” said Lisette Suder, an assistant district attorney for El Dorado County. “And that’s really not our job at all. Our job is to seek justice.”

She told the judge: “We are asking the court to legally undo a wrong that has been nearly 40 years in the making.”

Connie Dahl died of a heart attack in March 2014. She was 48 years old.

(Jarred Lange)

Connie Dahl was 19 in 1985 when she and her then-boyfriend, Ricky Davis, returned from a night of partying to find the desecrated body of a house guest in the upstairs bedroom.

Police quickly focused on Davis (and Dahl) as suspects and not witnesses. But they were not charged and went their separate ways.

In 1999, investigators reopened the cold case and relentlessly questioned Dahl. Although Dahl initially maintained her innocence, investigators pressured her to adopt a version of the crime they believed to be true, in which Dahl helped Davis carry out the murder.

El Dorado County Assistant District Attorney Lisette Suder listens to Ricky Davis make a statement in court on Friday.

(José Luis Villegas / For The Times)

Davis was convicted in 2005, largely based on Dahl's false testimony, and sentenced to 16 years to life in prison. He was exonerated in 2020 thanks to DNA tests that proved his innocence. DNA also led police to the real killer, who pleaded guilty to the murder in 2022 and is now in prison. The same evidence showed that Dahl was not involved in the crime, but she had died in 2014 and no one thought to clear her name.

Times reporters informed El Dorado County District Attorney Vern Pierson of the oversight and that Dahl's children had never been informed that she was no longer considered guilty. Pierson was quick to ask the court to vacate the conviction and declare Dahl factually innocent.

On Friday, Pierson was reunited with her two sons, Nick and Jarred Lange, at the El Dorado County Courthouse. Davis joined them.

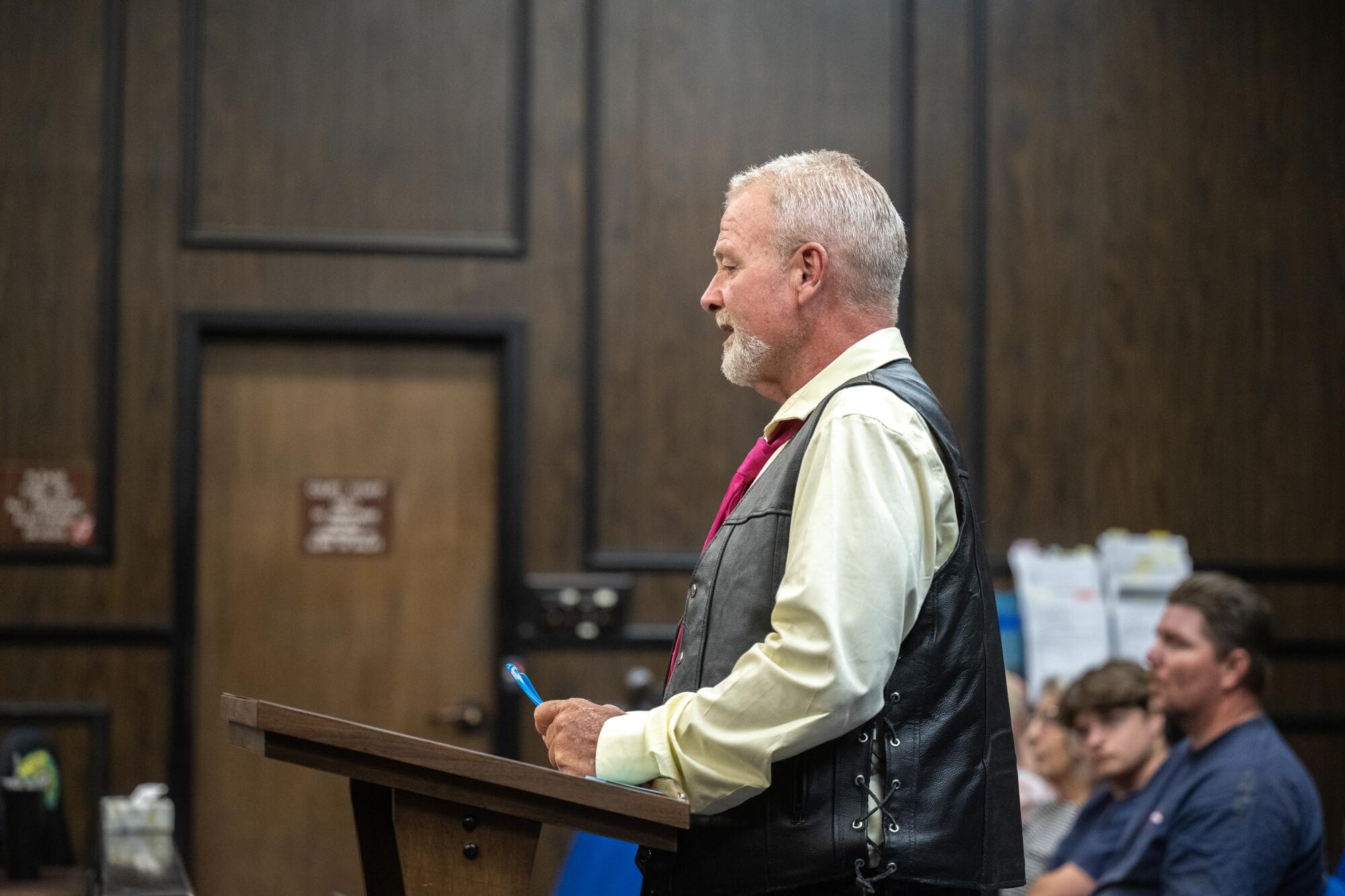

Standing outside the courtroom before the hearing, Jarred and Nick met Davis for the first time. A colorful character who wore a bright pink tie and a leather biker vest and showed up on a red Harley-Davidson, he was just the kind of man their mother would fall in love with, they agreed.

Ricky Davis, left, speaks with the El Dorado County District. Lawyer. Vern Pierson in court on Friday.

(Jose Luis Villegas / For The Times)

“I'm sorry for what happened to you,” Jarred told Davis.

“Look, I was never really angry,” Davis told the brothers. “It was a very life-changing time for your mother.”

Davis, who has spent years reviewing Dahl's interrogation transcripts, trying to understand why he would implicate them both in a crime they had nothing to do with, added: “I think she was indoctrinated.”

“Yeah, and she started questioning herself,” Jarred said.

Davis would later tell the judge: “I want to see her vindicated. She was as innocent as I was. She was wrongfully convicted in a different way.”

These men arrived almost immediately at the courthouse on Friday morning, passing one by one through the metal detector, even the prosecutor was forced to remove his belt by an officer who did not recognize him. They greeted each other awkwardly as they put their seat belts back on, then walked up the wide staircase to wait outside Judge Larry E. Hayes' courtroom.

Ricky Davis heads to court on Friday.

(José Luis Villegas / For The Times)

Then they filed in: The Lange brothers, who flew in from Oregon, took seats in the front row; Davis sat behind them. Other lawyers and relatives of those charged in court on unrelated matters looked on in surprise.

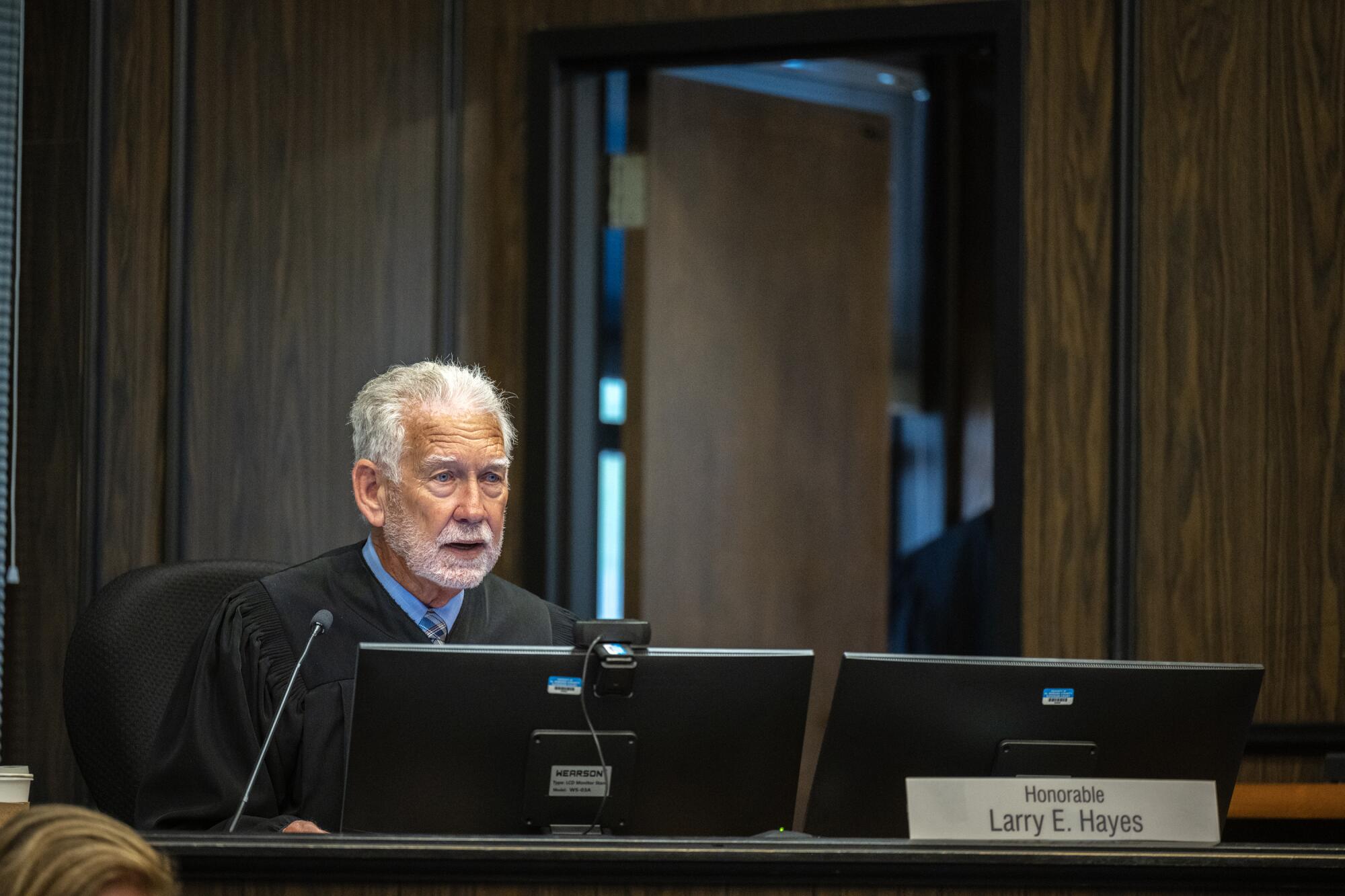

“My deepest condolences to the family and the people who have been traumatized by this whole situation,” the judge said. “But I hope they leave the courtroom with justice done in the right way.”

The Lange brothers remained impassive. Nick, the father of 1-year-old twins, hesitated when the judge asked them if they wanted to talk.

Finally, he stood up: “I wish I could be here for this. She has been gone for over 10 years and in the 20 years I was with her she was not well most of the time. I wish she could be here and had received the help she deserved.”

Judge Larry E. Hayes presided over the hearing that exonerated Connie Dahl.

(Jose Luis Villegas / For The Times)

Previously, Jarred and Nick described how their mother's arrest ruined their lives.

They were moved from one relative to another with little stability or understanding of why their mother was gone. When she was finally released in 2006 and allowed to return to Oregon on parole, her background made it nearly impossible to find work or housing. For a time, they were homeless and lived in a tent.

After the hearing, the Lange brothers said they felt a sense of closure. It wasn’t until they met with a Times reporter in April 2023 that they learned the full story of what had happened to her, Nick said. Since then, he added, he’s been thinking about everything his mother went through and how the wrongful conviction affected them all.

“Who knows what life could have been like, but it could have been better in almost every way,” Jarred said.

Pierson, the district attorney, apologized.

“We cannot take back or turn back the time she spent in custody here … and the negative consequences that this had on her life and yours,” Pierson told the Lange brothers in court. “But we can take responsibility and try to do better in the future.”

Ricky Davis approaches the lectern to speak in court as Connie Dahl's sons Nick Lange, left, and Jarred Lange, right, sit with Julie Ehrlich, a victim witness advocate, at the El Dorado County Courthouse.

(José Luis Villegas / For The Times)

Pierson also promised that nothing like this would happen again. This case convinced him that the methods authorities use to interrogate suspects are outdated and can lead to false confessions and wrongful convictions.

Since exonerating Davis, he has been on a quest to change the way detectives are trained, so that California and the country move toward what he describes as evidence-based tactics that seek truth and facts over facts. confessions. In 2021, he supported legislation that would have banned the type of interrogations Dahl endured. But that bill was vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, who cited the high price of retraining detectives across the state.

Pierson, working with the Innocence Project, succeeded with a second law that prohibited lying to suspects under 18 years of age. That law went into effect this year.

The district attorney has also declined to prosecute any cases in his jurisdiction in which confessions were obtained using this technique, and organizes training in science-based methods for investigators across the state.

“My goal has always been to change the way we train officers to conduct interviews and interrogations,” he said.

The Lange brothers emerged from the dark courtroom Friday morning into the bright Northern California sunshine. They were struck by how pleasant Placerville seemed, the charm of a gold rush town on a summer day.

“She always told us that at some point we were going to be the only thing each of us would have,” said Nick Lange, right with his brother. “She was right”.

(Isaac Wasserman / For The Times)

Once, her mother had walked this stretch of shops and bars on Main Street in search of fun: a carefree young woman who didn't understand how precarious her freedom was until she lost it.

They wished they could be there under different circumstances and that she could be there too. Exoneration was important and even healing, but it was not justice.

“It's good that this has come to an end,” Jarred said. “It was a long time coming.”