It’s not just toxic chemical waste and mysterious barrels littering the seafloor off the coast of Los Angeles. Oceanographers have now discovered what appears to be a huge military weapons dump.

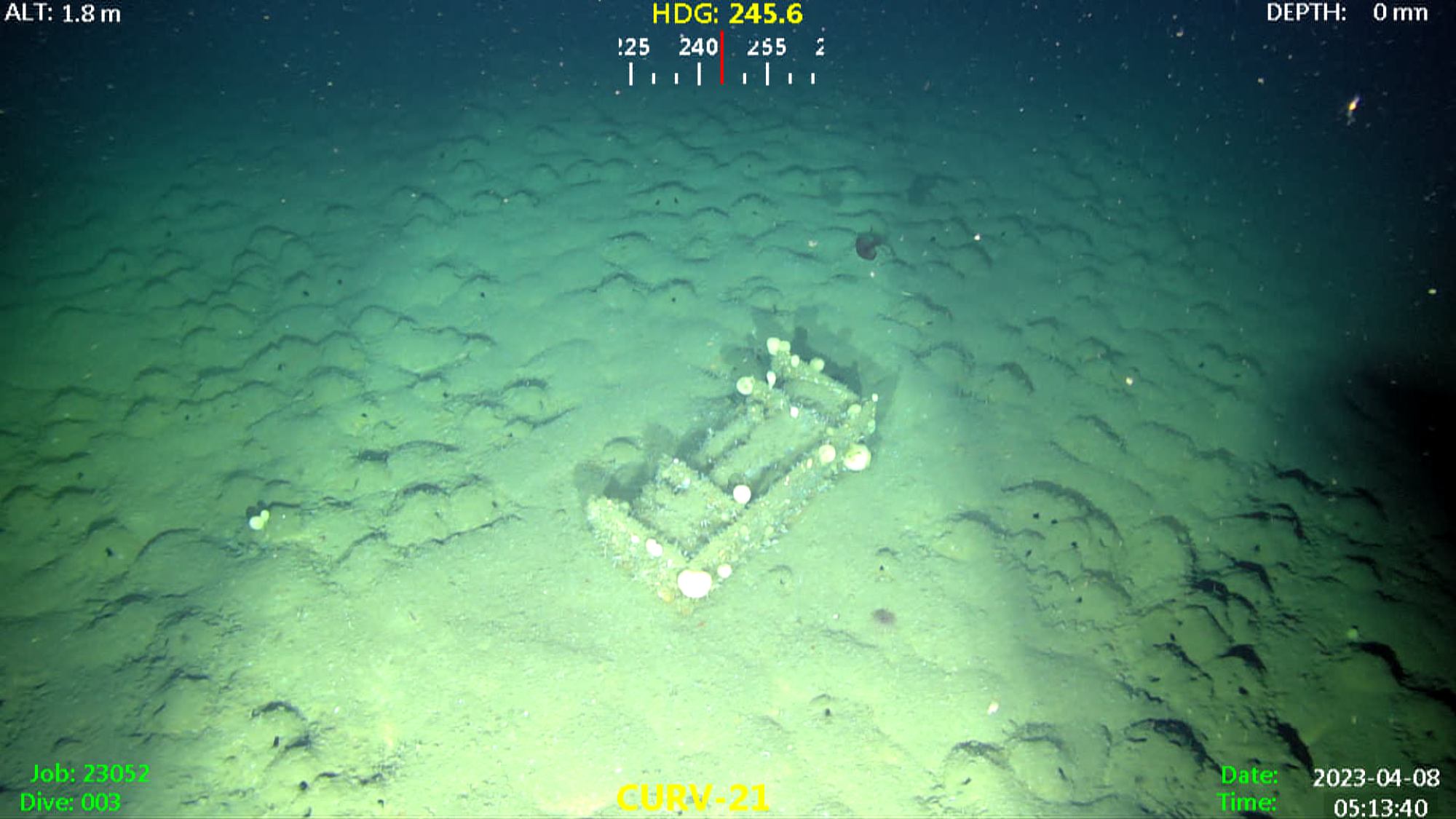

As part of an unprecedented effort to map and better understand the history of ocean dumping in the region, scientists have found a multitude of discarded ammunition boxes, smoke floats and depth charges lurking 3,000 feet underwater . Most appear to be from the Second World War era and it is still unclear what risk they could pose to the environment.

“We started finding the same objects by the dozens, if not hundreds, consistently… In fact, it took us a few days to really understand what we were seeing on the seafloor,” said Eric Terrill, who co-led the deep-sea study. of the ocean with Sophia Merrifield of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego. “Who knew that right in our backyard, the more you look, the more you find.”

Scripps researchers were able to group most of the military debris they found underwater into four general categories: ammunition boxes, smoke floats, and two types of World War II depth charges.

(UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Among the documented munitions were Hedgehog and Mark 9 depth charges, explosives typically dropped from warships to attack submarines. Investigators also identified Mark 1 smoke floats: chemical smoke munitions that ships launched to mark locations or conceal their movements.

These findings, made public on Friday, build on an impressive 2021 underwater sonar study that identified tens of thousands of barrel-shaped objects between Los Angeles and Catalina Island. Merrifield and Terrill’s research team, assisted by an unusual partnership with the U.S. Navy’s Overseer of Salvage, set sail again last year, this time with even more advanced sonar technology, as well as a deep-sea high-definition that sought to visually identify as many objects as possible.

Disposing of military waste at sea was not uncommon in decades past, but this once-forgotten history of ocean dumping continues to haunt our environment today. (In fact, a World War II practice bomb washed ashore last week in Santa Cruz County after a particularly high tide.)

The U.S. Navy has confirmed that what the Scripps team discovered “is likely the result of World War II-era munitions disposal practices,” noting in a statement that “the munitions disposal at sea at this location was approved at that time to ensure safe disposal when the warships returned to the American port.” Officials are now reviewing Scripps’ latest findings and “determining the best path forward to ensure the risk to human health and the environment is appropriately managed.”

catch up with more coverage

Public interest in the legacy of ocean dumping in Southern California has intensified since the Los Angeles Times reported that up to half a million barrels of acidic DDT waste had disappeared into the ocean’s depths, according to old shipping records and a report from UC Santa. Barbara’s study that provided the first real insight into how the Los Angeles coastline became an industrial dump.

Since then, dozens of marine scientists and ecotoxicologists have met periodically to discuss data gaps in our understanding of DDT, a pesticide (banned in 1972) that was largely manufactured in Los Angeles and was so powerful it poisoned birds and fish. . Congress, at the urging of U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Calif.) and the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), allocated more than $11 million to work on the issue, with Gov. Gavin Newsom also pushing even more research with an additional $5.6 million.

In another recent plot twist, an exhaustive historical investigation by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency concluded that pesticide waste was not actually contained in barrels, but rather the chemicals were dumped directly into the ocean from huge tanker barges. In the process of unearthing old records, the EPA also discovered that from the 1930s to the early 1970s, 13 other areas off the coast of Southern California had also been approved for the dumping of military explosives, radioactive waste and various refinery byproducts, including 3 million metric tons of waste oil.

“When the UC Santa Barbara team first discovered deep-sea spilling in more detail, the response was, ‘Oh my God, this is the tip of the iceberg.’ And now we are seeing how big this iceberg is; We don’t even know how big it is yet,” said Mark Gold, an environmental scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council who has worked on the DDT problem since the 1990s.

“What’s scary, as if we needed it to be scarier, is that we now have over 100 square miles of contamination from this landfill, with high concentrations of DDT at depths that no one has ever looked at before, and now we’re seeing all the others too. things that were thrown,” he said. “And it’s just what we see, from a large munitions standpoint, as opposed to: How do we know there weren’t other chemicals that were dropped by the Department of Defense?”

David Valentine, the University of California, Santa Barbara scientist whose marine research team first found dozens of eerie-looking barrels, also emphasized that less visible pollution is more of a concern. The legacy of DDT pollution still haunts sea lions and dolphins in mysterious ways, and other researchers have traced high concentrations of this everlasting chemical up the marine food chain to critically endangered condors.

“We can’t lose sight of the 500-pound gorilla down there, which is the enormous amounts of chemical waste that was dumped and scattered all over the place,” said Valentine, who noted that the contents of the barrels his team discovered remains a mystery.

“Now that we know that the military had their thing and that chemical spills were being dumped in large quantities, it really begs the question: So what else might have required being contained in these barrels?” he said.

Valentine, who has also been working with several scientists to understand how DDT might be being remobilized from the seafloor, added that Scripps’ latest high-resolution images are critical to helping the entire research community understand what the seafloor is really like. .

In fact, the deepest parts of the seafloor between Los Angeles and Catalina Island have never before been mapped in this way. Locating specific objects in such a wide swath of seafloor has been compared to searching for the smallest needles in the largest haystack.

On the most recent expedition, a team of nine Scripps researchers and 10 Navy Salvage Supervisor specialists scanned the seafloor for more than 300 hours, capturing as many images as possible with high-resolution technology not normally available for the scientists.

Patterns began to emerge. Object after object came into view, and scientists found themselves processing and interpreting an overwhelming amount of data in real time.

Terrill, an oceanographer who also specializes in exploring the deep sea for downed military aircraft as co-founder of the nonprofit Project Recover, turned to an underwater archaeologist on his team to help him identify the ancient military remains. .

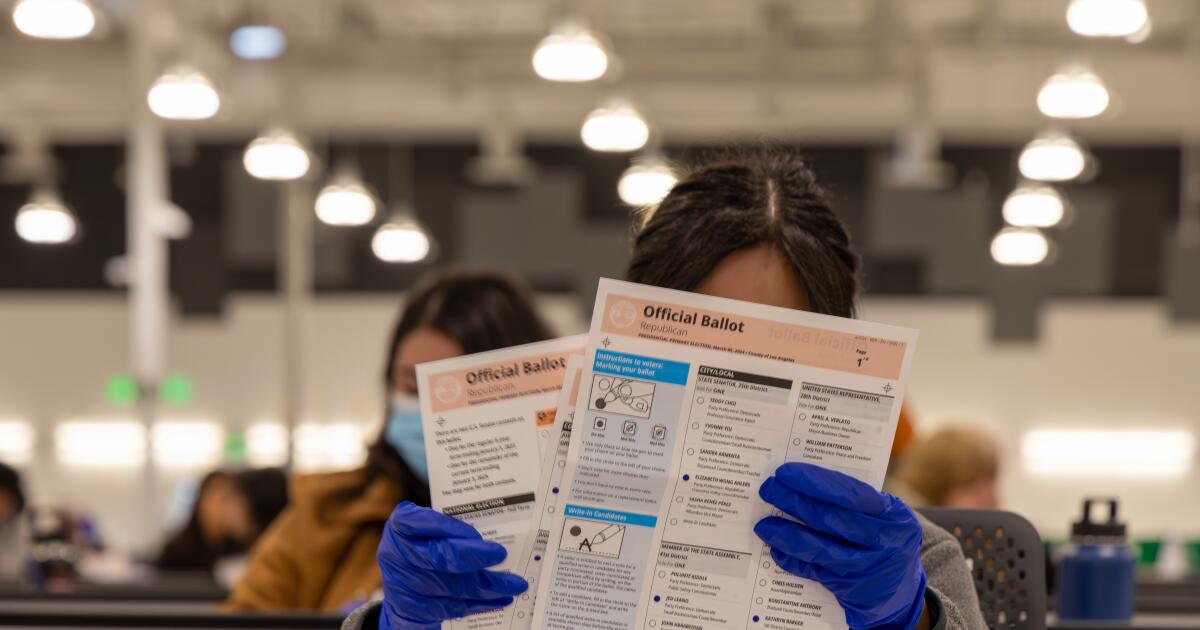

Using an advanced deep-sea camera, Scripps researchers found numerous World War II-era ammunition boxes on the seafloor off the coast of Los Angeles.

(UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

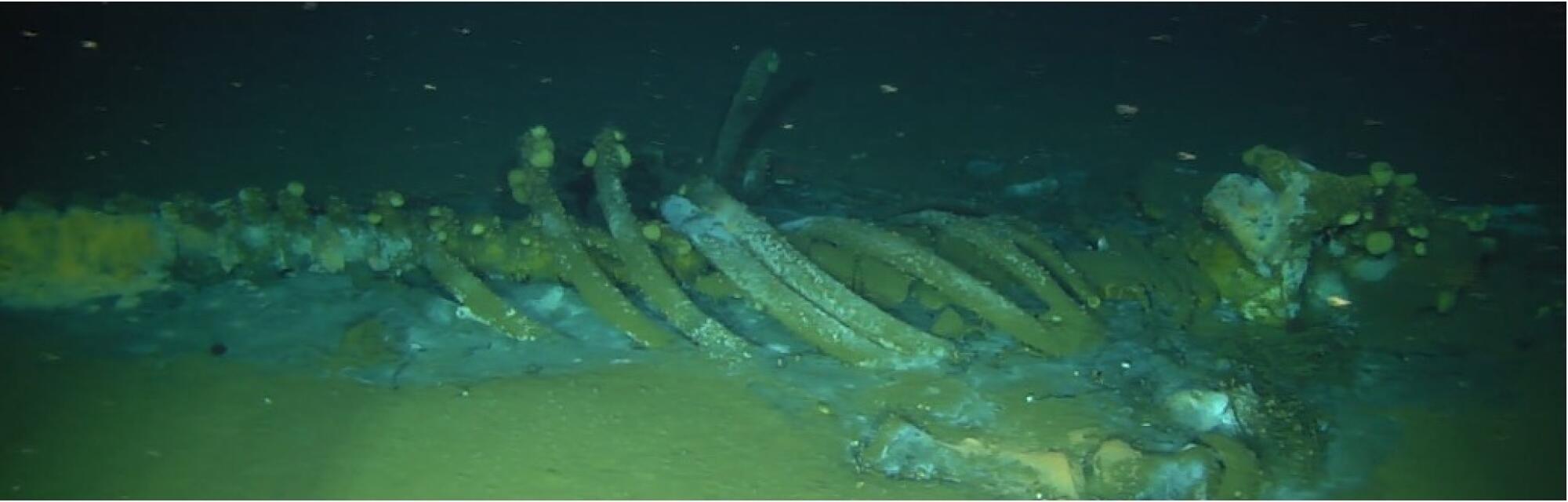

Another surprise for researchers was the discovery of dozens of whale skeletons and carcasses, known as whale falls. Advanced sonar readings potentially identified more than 60 whale falls, and researchers were able to visually confirm seven with their camera system.

Craig Smith, a professor emeritus of oceanography at the University of Hawaii who has dedicated much of his life to studying whale falls, said this finding is particularly groundbreaking in his field. Worldwide, only about 50 natural whale falls have been identified, so locating 60 more just off the coast of Los Angeles essentially doubles the number of known whale falls.

Many questions remain about why there appears to be such a high concentration of slowly decomposing dead whales off the coast of Southern California. Smith and his colleagues are eager to study this further.

In a recent underwater study, researchers also found numerous sunken whale carcasses, known as whale falls.

(UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

“When we do calculations at the population level, we estimate that there may be on the order of 600,000 or more whale falls in the global ocean. But they fall more or less at random, so they’re hard to find,” said Smith, who noted that whale falls make for fascinating but elusive ecosystems for deep-sea creatures.

Merrifield, the physical oceanographer who co-led the Scripps expedition, noted that there is still an immense amount of new data to refine and analyze. His team was able to capture high-resolution images of different textures of the seafloor, for example, as well as mounds that could indicate small burrowing animals that could remove any chemicals half-buried in the sediment.

“New technologies are really changing the way we look at the seafloor, and there are interdisciplinary problems, from microbiology and remediation, to chemistry, geology, physical oceanography and transportation, that require bringing together all kinds of specialists,” he said. “I hope the takeaway here is that maybe we didn’t find what we thought we were going to find, but we found a lot of really important objects and ideas that will hopefully lead to really good scientific results for the community.”