California's richest farming family is proposing an expansion of industrial warehouses in Kern County that would fundamentally reshape the economy in the southern San Joaquin Valley.

Aside from Kern, Stewart and Lynda Resnick, the billionaire owners of Wonderful Co., are best known for pomegranates and pistachios. But for more than a decade, they have also owned a master-planned industrial park in the town of Shafter, northwest of Bakersfield, that houses distribution centers for Fortune 500 companies like Target, Amazon and Walmart.

Now, looking to capitalize on the radical shift toward online shopping, the Resnicks want to position Kern County as a new frontier for industrial-scale warehousing that is key to connecting customers with their products. Wonderful is trying to double the size of its industrial park by converting 1,800 acres of its own almond groves into additional warehouse space.

And it is carrying out costly infrastructure projects that company leaders say will mitigate the impacts of that expansion.

Wonderful says its vision for an expanded Wonderful industrial park is starkly different from the thousands of sprawling distribution centers that have gobbled up neighborhoods in California's Inland Empire. The influx of mega warehouses in Riverside and San Bernardino counties has created thousands of jobs, but also relentless truck traffic and poor air quality that have sparked a backlash.

The Wonderful Industrial Park is located next to the railroad tracks on more than 1,600 acres of former farmland, several miles from downtown Shafter. With the exception of a group of houses on the other side of the tracks, the surrounding area is mainly agricultural. Wonderful describes the park as a job creator in a region hit hard by economic changes in agriculture and oil.

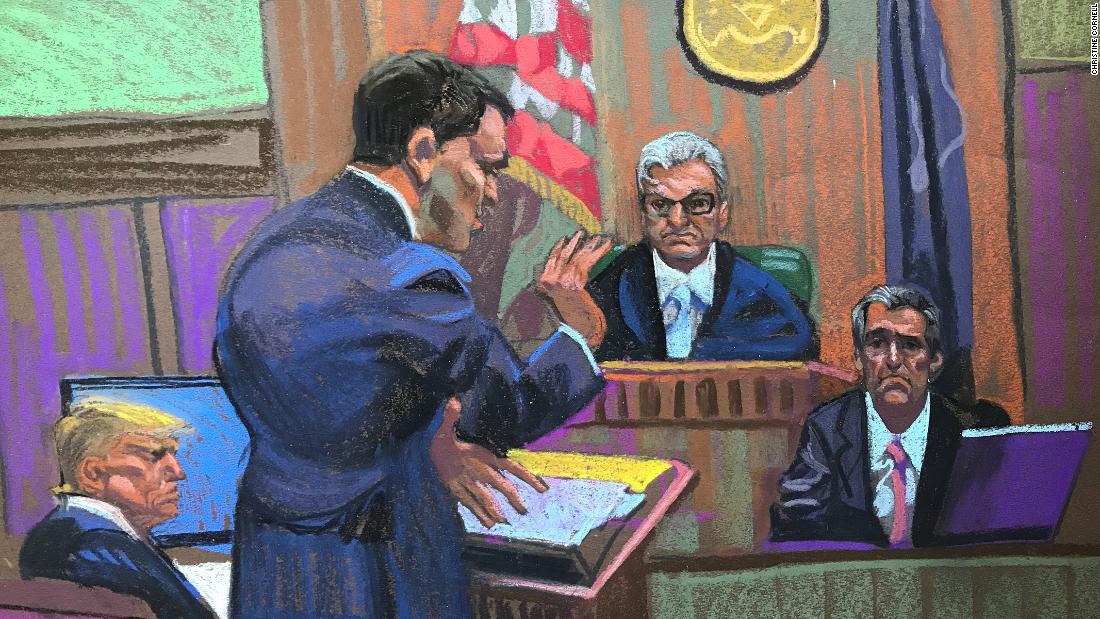

Wonderful Co.'s plans for a mega storage complex near Shafter include a new six-lane highway to ease traffic on State Route 43 (pictured) and other area highways.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The company is working with local officials on plans for a new highway that would move trucks away from downtown Shafter. It also plans to funnel at least $120 million toward an inland rail terminal, which is expected to be completed next spring. The goal is to move more goods from coastal ports by rail to Shafter, reducing traffic on State Route 99, already one of the busiest trucking routes in California.

If all goes as planned, Shafter would go from a small town, with a population of 20,162, to an international trade center; and Kern County, a region that has long valued what is extracted from the earth, would become ground zero for the growing global movement of goods.

Many Shafter residents say the opportunity for stable, relatively well-paying work in areas other than agriculture and oil would be a welcome addition. But some worry that doubling down on an industry that will bring more truck and train travel to one of the country's most polluted corridors can't help but have negative consequences.

“I understand that the company says it will bring jobs; this is true to some extent,” said Gustavo Aguirre, deputy director of the Delano-based Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment. “But it is also true that it will bring impacts to health and the environment that will impact the neighbors who live near the industrial park.”

As John Guinn tells it, the Wonderful Industrial Park was created out of necessity.

Several decades ago, as big-box retailers moved into San Joaquin Valley cities, Main Street's shoe and textile stores struggled to survive. City officials sought to create employment opportunities.

“The world was changing,” said Guinn, who worked as city manager in Shafter for 17 years. “We had to find a way to do something different.”

So Shafter rezoned a portion of land between Highway 99 and Interstate 5, along the BNSF rail line, and that became the industrial park. The first tenant was Target, which built a roughly 2 million-square-foot warehouse in 2003.

In 2011, the Resnicks' real estate division purchased the development. Guinn retired from the city in 2014 and joined Wonderful as executive vice president and chief operating officer of the real estate team. It's a role, he said, that will allow him to bring to light his broader vision for Shafter.

Today, the Wonderful Industrial Park typically builds and leases million-square-foot warehouses. Just over half of the 1,625 acres already zoned for industrial buildings has been developed.

It has proven to be a profitable way to diversify for Wonderful, which also owns Fiji Water and Justin Vineyards, at a time when almond prices are falling and water supplies are limited.

According to Wonderful, the industrial park has generated around 10,000 jobs, including warehouse employees, truck drivers and shipping logistics services. With the planned expansion, company leaders said, the complex could eventually generate 50,000 jobs.

Warehouses are becoming increasingly mechanized, which means more robotics and less need for staff. “Warehouses create and destroy jobs,” says Ellen Reese of UC Riverside.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Marco Avendaño, 27, has been working for almost a year as a forklift operator for CJ Logistics in the industrial park. Avendaño, who did not go to college, said he learned new skills and is now interested in taking a management position in the company.

“Even though it started as a job for me, it made me get into a professional mindset,” he said.

His schedule (9:30 p.m. to 6 a.m.) works well for him and his fiancée, a librarian, who are raising three children. During his night shifts, he said, “we still strengthen that bond with our family.”

Avendaño previously held two other jobs in the industrial park: at a manufacturing plant that closed and as a contractor at a Walmart warehouse. At his current job, he said he has received several raises and earns $22.69 an hour, “more than I've ever made an hour.”

As the park expands, the number of jobs created with each warehouse is likely to decrease. Warehouses are becoming increasingly mechanized, which means more robotics and less need for staff. Technological advances could hinder Wonderful's job projections.

“Warehouses create and destroy jobs,” said Ellen Reese, co-director of the Inland Empire Community and Labor Center at UC Riverside. She noted that automation is reducing the number of warehouse employees, but it doesn't necessarily make jobs safer.

“A lot of research actually suggests that more automated warehouses have higher injury rates than less automated warehouses,” he said.

Guinn acknowledged that more efficient warehouses will require less labor. But the remaining jobs, she said, will be more technically skilled and require higher wages.

Inside the Walmart warehouse, for example, an automated system builds pallets tailored to the needs of individual stores more quickly and accurately than a team of humans. The facility employs only 400 people on all shifts, many of whom are highly trained equipment operators and skilled at troubleshooting technical problems. The average salary ranges between $28 and $29 per hour.

“I don't think it's a bad thing if we can do twice as much with half the labor,” Guinn said. “What I think is bad is having a lot of people who don't have jobs or who have jobs that aren't very good.”

Wonderful says it is helping ease the transition with an on-site career center that trains workers for the most skilled jobs.

Two men participate in an apprenticeship program at the Wonderful Career Center in Shafter, using virtual reality headsets that simulate forklift operations.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

One morning in March, Luis Chapa wore virtual reality glasses inside a classroom at the career center and simulated driving a forklift while standing. He is training as a maintenance technician and gaining work experience and college credits through a free, year-long program.

Before enrolling in the apprenticeship program, Chapa, 37, worked for two and a half years in the Bakersfield oil industry. The work of a demolition crew was grueling and dirty, and Chapa, a father of two, said his pay stagnated at $26 an hour.

He decided to make a career change and is confident that the training will lead to a higher-paying position at Wonderful or another company in the industrial park.

“My conclusion in the oil fields would pretty much be my starting point for where I'm headed,” Chapa said.

In addition to their farming empire, Stewart and Lynda Resnick are known for their philanthropy, which includes major donations to climate research, as well as money for scholarships and wellness centers in the valley towns where many of their workers live. So Wonderful is keenly aware of the optics as the company positions the park to have a much larger footprint.

Guinn and others argue that, with proper planning, expansion need not mirror trade-offs in the Inland Empire.

The company plans to build the Wonderful Pacific Terminal in the industrial park, so that trains can transport cargo from California ports directly to the facilities. Once built, Guinn estimates that 20% of imported containers could arrive by rail, and that each train would replace the equivalent of 240 trucks.

The Wonderful Company, co-owned by billionaires Stewart and Lynda Resnick, says the expansion of its industrial park in Shafter will create new jobs in a region shaken by economic shifts in oil and agriculture.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Wonderful is also touting plans for a six-lane highway, the Central Valley Green Pass, which would act as a relief valve for Highway 99.

Both projects are still in the planning phase and need multiple approvals.

As another carrot, Wonderful agreed to create a fund for the local park district if Shafter officials approve the company's rezoning request. Tenants of the new warehouses would pay 2 cents per square foot per month (or $240,000 a year for a million-square-foot warehouse) to a fund dedicated to improving sports programs, arts and crafts, and community events.

Aguirre, of the Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment, is helping negotiate a broader community benefits agreement aimed at ensuring that people living in and around Shafter get more than jobs from the agreement.

“The neighbors recognize that [this project] They could generate jobs, but they have a price,” Aguirre said. “Because of this, they say, 'What are you going to do for our community?'”