As night fell in her Glendale apartment, Dara Bruce fed her rats George and Fred, poured herself a glass of water and called a complete stranger to talk about the dangerous virus detected in her blood.

“Is now a good time to talk?” she asked.

Bruce is a volunteer in the long-standing fight against hepatitis C. This stealth killer claims the lives of approximately 14,000 Americans each year, although it can be easily cured with a few months of pills. Many people have no idea they are infected and go years without symptoms before the blood-borne virus ravages the liver.

However, public funding to combat hepatitis C is so scarce that in Los Angeles County (an area more populous than many states) the crucial work of contacting the infected is being done by unpaid emissaries like Bruce through a fledgling initiative called Project Connect.

Project Connect, a partnership between USC and the county public health department, trains volunteers to call people who have tested positive for the virus to make sure they know their results and encourage them to get the medications they need.

Sitting behind her desk filled with anatomy textbooks (the artifacts of the master's degree in integrative anatomical sciences she had just earned at USC), Bruce double-checked that she had the right person before breaking the news. Her reaction made her happy.

“Oh, beautiful!” she exclaimed after the man told her that he had been treated. “I love to hear that.”

It's not something I hear a lot. Among people contacted by Project Connect through mid-January, less than a third had received treatment. This echoes dismal statistics in the United States, where only about a third of people who test positive begin treatment within a year.

Nationwide, the number of new hepatitis C infections reported annually more than doubled between 2014 and 2021, exceeding 5,000. That same year, according to federal data, more than 107,000 long-term infections were discovered.

Some untreated infections may clear up on their own, but many persist, leaving people at risk of getting sick and dying. People with long-term infections can develop cancer or end up with liver scarring so severe that they need an organ transplant.

Experts say the high number of untreated patients is related to obstacles such as doctors unnecessarily referring patients to specialists and insurers making it difficult to obtain the pills, which can cost more than $20,000. Many do not realize they are infected: one in six people contacted by Project Connect volunteers did not know their test results.

The virus has taken an especially heavy toll on people who are often disconnected from health systems, including those who inject drugs or are homeless. And many at-risk people are unaware of the threat, including baby boomers who were infected long before the virus was identified.

Having an effective hepatitis C drug on the market is not enough to solve the problem, said Dr. Jeffrey Klausner, an infectious disease specialist at USC. It has to reach the patients who need it.

“It is necessary for people to be aware of their infection. You need people to be cared for by a treating provider. People need to receive their prescribed medications,” he said.

The problem is that “this is a disease without resources,” said Dr. Prabhu Gounder, medical director of the viral hepatitis unit at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

That's a common complaint across the country. In a national survey by hepatitis organizations, only 3% of local jurisdictions said they could make progress toward hepatitis elimination goals with the current level of federal funding.

“The funding is incredibly dangerous,” said Anne Donnelly, a member of the California Hepatitis Alliance who works with the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

The Biden administration has been pushing for billions of dollars to eradicate hepatitis C, arguing that the investment would pay off in the long term as Medicaid recipients would avoid liver diseases that require expensive care. An analysis published by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that the initiative would save the federal government more than $13 billion over a decade, exceeding its initial costs.

No one in public health is unaware of “what needs to be done to address hepatitis C,” said Sonia Canzater, associate director of the Infectious Diseases Initiative at Georgetown's O'Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law. “The problem has always been obtaining resources and political and social will.”

In Los Angeles, Gounder said budget constraints have made it impossible to implement a broad program for people with hepatitis C.

But “what if we just called them and made sure they were aware of their infection? Provide some education? Gounder wondered. “That alone is not going to solve this epidemic. But we thought it was something we could do with few resources to try to move the needle.”

The result was Project Connect. It started in April, tasking volunteers with reaching out to about 3,000 county residents, and is now adding another 3,000 cases to its lists.

Klausner said the project relies on the part-time efforts of five university employees and six to 12 student volunteers, many of whom need to log hours of field experience to earn graduate degrees in public health.

The public health department taught them the rules about patient privacy along with some basics about the virus and its treatment. USC volunteers now spend at least four hours a week texting people about their test results, based on reports that come to the county after patients test positive.

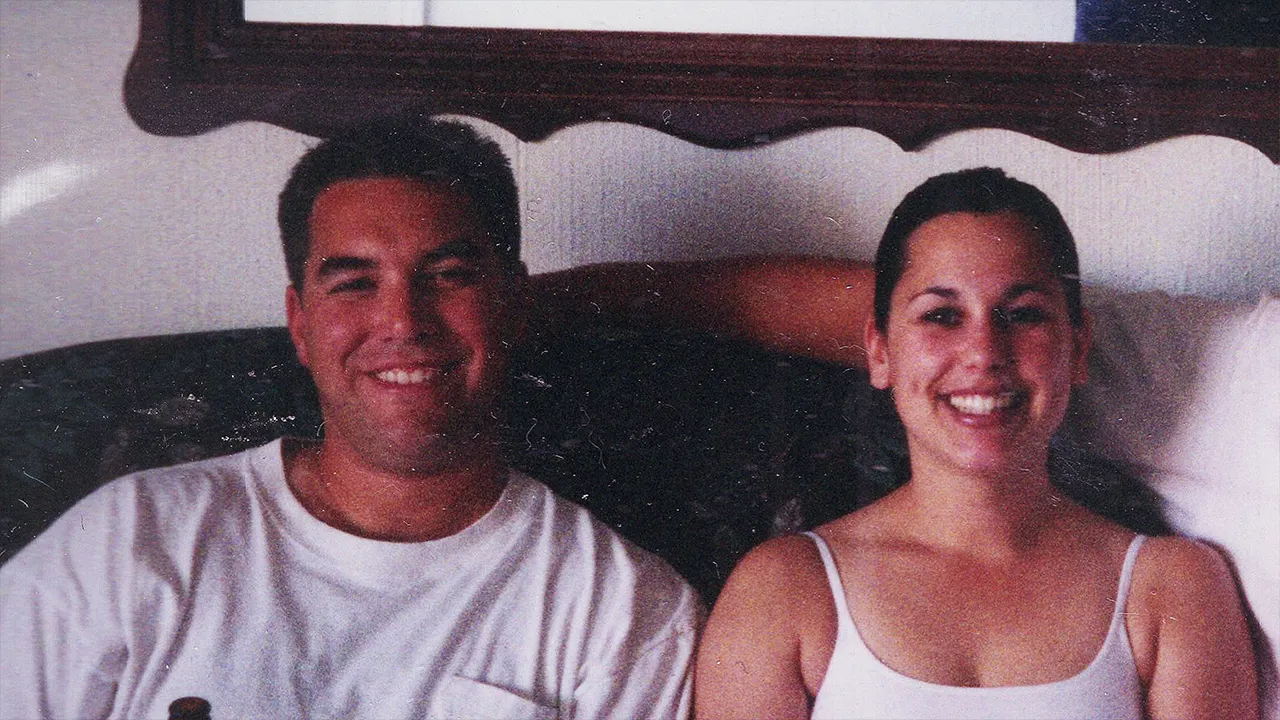

Learning the toll of the virus “excited me,” said Bruce, a 36-year-old former aerial arts artist.

Dara Bruce poses for a portrait in her home office in Glendale on January 11, 2024.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

Her interactions with hepatitis C patients left her surprised by “how prevalent it seemed to be among people from all walks of life,” but also by the huge disparities in what had happened to people after learning of their infections. “There were very different stories.”

Some people told him they wanted treatment but had no way to go to the doctor or couldn't take time off work. There were also patients who did not feel the urgency to receive the pills, since it can take years for serious health problems to develop.

To them, “it just didn't seem like something they should be dealing with right now,” Bruce said.

More than 70% of patients on volunteer lists cannot be reached, often because the phone numbers in their records were incorrect. The team does not have the resources to track people in government databases or on the streets, as public health departments do with other diseases.

The Los Angeles County Public Health Department is not spending its own money on Project Connect, relying entirely on USC volunteers and some support from county employees. Hiring a small team to tackle that work would cost about $250,000, Gounder estimated; It is not a huge sum but “it is not feasible with the budget we have.”

Its viral hepatitis team receives about $1.2 million in grants from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the California Department of Public Health, but that must cover the costs of hepatitis A and B, as well as the C.

By comparison, the county receives approximately $97 million in state and federal grants to address HIV. Gounder said funding for hepatitis C has been so scarce that she cannot determine the exact number of cases in the county, but statewide estimates suggest it rivals or exceeds the number of HIV cases.

Both diseases can be fatal and put other people at risk of infection if left untreated. But the push to bring antiretroviral treatment to HIV patients was fueled by “an incredibly active community” that included wealthy people, said Dana Goldman, dean of the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy.

The same kind of mobilization hasn't happened with hepatitis C patients, he said, but “that doesn't mean they're any less deserving.”

Relying on volunteers has its limits: Among other things, work can be interrupted during university holidays or exam periods, Klausener said. And phone calls only go so far: Among the untreated patients Project Connect was able to follow up after three months, only 20% had received the pills.

Klausner believes the county has a responsibility to fund paid staff. And he wants outreach teams to be able to schedule people for treatment and help them with transportation vouchers, child care or other help — the “link to care” he says has been missing.

But Bruce said even a phone call can be meaningful to those on the other end of the line. “It's about listening to people and their stories,” she said.

At his Glendale apartment, Bruce asked if the man on the phone had time to ask a few more questions. The answers would help officials get a clearer picture of who is receiving treatment and who is not.

“I'm glad you're a treatment success story,” he told her before wishing her goodnight.

Bruce called the next number, but they hung up on him. He called again and left a message with his phone number.