More than a month after their arrests, a group of Southern California street vendor advocates are still being held without bail as they await trial on charges of conspiracy, assault and other violent crimes.

Defense lawyers for the activists argue that police are singling them out because they have been openly critical of law enforcement. The case illustrates what can happen when enthusiastic protesters take to the streets and their passionate advocacy results in violence.

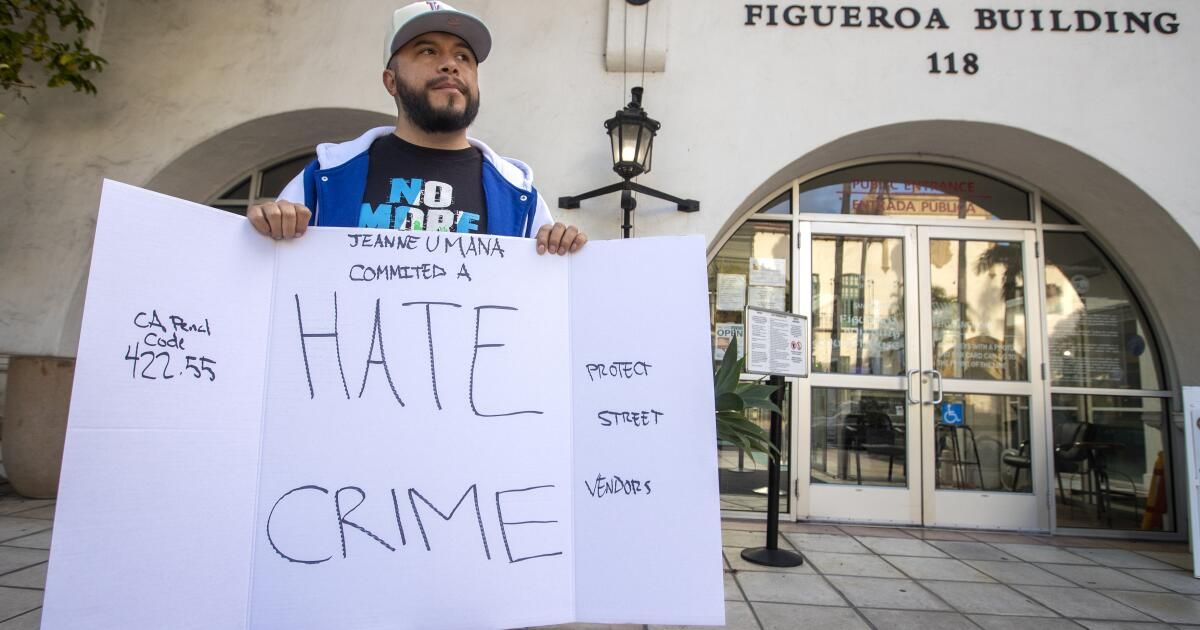

Among the group is Edin Alex Enamorado, 36, who in recent years has organized protests outside the homes and workplaces of people he believes deserve public shaming, either because they were recorded saying something racist or because they were accused of attacking. a traveling salesman.

Enamorado's brand of activism begins when he highlights an issue on Instagram or TikTok and then takes to the streets with a megaphone to ramp up his campaign.

Prosecutors say members of the group, referred to by supporters as the Justice 8, are too big a threat to the community to be released on bail. They were arrested on December 14 after a multi-agency police investigation, and all but one have remained in prison since.

Defense attorneys argue that the San Bernardino County district attorney's office characterized the defendants as accomplices simply for exercising their First Amendment rights and organizing their efforts through social media or text messages.

The conspiracy charge is “whatever the prosecution wants it to be,” defense attorney Dan Chambers said in court. He admonished the prosecution for treating the activists as a “wandering mob.”

The six people arrested along with Enamorado and his partner, Wendy Luján, 40, were David Chávez, 28; Stephanie Amesquita, 33; Gullit Eder Acevedo, 30; Edwin Pena, 26; Fernando López, 44; and Vanessa Carrasco, 40 years old.

The group is accused of intimidating and attacking people in Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties in three separate incidents in September. In each case, authorities allege, activists were organizing a protest when targets or bystanders of the action were threatened or beaten.

American Civil Liberties Union attorney Emerson Sykes is not familiar with the details of the case against the Justice 8, but said arrests after a protest are nothing new and typically serve their own purpose.

“Civil disobedience is a time-honored tradition by which people knowingly and voluntarily break laws, whether they believe they are unjust or to highlight other injustices, and intentionally suffer the consequences of breaking the law to defend their legal points, their moral points and their interests. ethical point,” Sykes said.

But sometimes protests lead to arrests for illegal actions that followed. And who can be held responsible for those illegal acts is a difficult question to untangle, Sykes said.

Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, for example, there was a massive surge in nationwide protests against police violence that then resulted in an aggressive crackdown by law enforcement, Sykes said. Conspiracy, rioting, and other charges were brought against the protesters even though they may not have been involved in the violence or destruction of property that occurred afterwards.

In another example, a Louisiana court ruled that a Baton Rouge police officer hit by a rock during a Black Lives Matter protest march in 2016 could sue its leader, DeRay Mckesson, a prominent civil rights activist. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a lower court's ruling and concluded that the officer's lawsuit does not violate the First Amendment and Mckesson could be liable for damages; The ACLU has appealed the ruling to the Supreme Court.

“We believe this is a horrible line of argument that would have a devastating and chilling effect on protesters,” Sykes said.

Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law, is not familiar with the evidence against Enamorado, but says there is no First Amendment protection “for engaging in an assault.”

“That's not a First Amendment issue,” said Chemerinsky, who joined a legal brief to overturn the lower court's ruling in the Mckesson case.

Advocating the use of force or violence does not eliminate someone's right to free speech, but there has to be some proven specific intent, Chemerinsky added.

Like Mckesson, Enamorado often called on his hundreds of thousands of followers on social media to join the protests, reaching people who would otherwise not hear about violence against street vendors or excessive use of force by the police.

“Social media provides an additional form of civic engagement,” said Chris Zepeda-Millán, chair of Labor Studies at UCLA. “Some people may not feel comfortable in crowds, but we have to ask ourselves: does that mean they should not participate in public dialogue and politics at all?”

Enamorado's brand of activism manages to bridge the gap between people who only engage in activism through social media and those who want to be physically on the streets, Zepeda-Millán said, but it's unclear whether one leads to the other.

Hundreds of supporters packed into the courthouse in Victorville, about 75 miles east of Los Angeles, in late December to hear the case against the eight activists. Many wore T-shirts that said “Free the Justice 8” and “Stand Up Fight Back.”

“I admire Alex because he is the type of person who raises funds for people who don't always have a voice. He can give them hope,” said Alfonso Grijalva, who drove several hours from Stockton and slept on a couch the night before to attend one of the hearings. Many of Enamorado's followers refer to him by his middle name.

After several hours of discussion between defense lawyers and the prosecution, seven of the eight activists were denied bail.

“That's not the Alex I know,” Grijalva said, unfazed by the prosecution's framing of Enamorado as a threat. “A lot of things about helping people are coming out. “That's what Alex is all about.”

San Bernardino County Superior Court Judge Melissa Rodriguez granted bail to Acevedo, 30, who was present at a protest in Victorville and was charged with assault. That charge was later reduced to a misdemeanor.

She ordered him not to contact any of the co-defendants in the case while he was out on bail and banned him from using social media.

Nicholas Rosenberg, Enamorado's attorney, said his client would agree to similar stipulations if the court allowed him to post bail and await trial under house arrest.

“We have activists jailed without bail,” Rosenberg said. “It is common for a court to order house arrest, but not a social media block.”

Authorities say the charges against the eight stem from three incidents that involved much more than activism:

- After sharing a video of a security guard attacking a group of street vendors, Enamorado and other activists confronted the guard on September 3 while he was sitting in his car and then again when he approached the group as they protested outside a supermarket in Pomona where he worked. . Prosecutors allege that some of those same activists later beat the guard inside the market and sprayed him with pepper spray.

- On Sept. 24, Enamorado and other protesters blocked the entrance to a San Bernardino County sheriff's station in Victorville, prosecutors allege, and at least one off-duty sheriff's deputy felt threatened when the group approached his vehicle. civil. The group's protest focused on an officer accused of body-slamming a 16-year-old girl at a high school football game.

- Two other men who were simply too close to protesters were also attacked, prosecutors allege. One was at a Pomona police station on Sept. 3 and the other confronted protesters as they walked in front of his wife's car near a car wash in Victorville on Sept. 24.

- In 2017, Los Angeles authorities identified Enamorado as the subject of a sexual assault investigation, according to a redacted document provided to The Times under a California Public Records Act request. But the victim refused to cooperate or press charges, so the matter was dropped.

Years before the court hearing, Enamorado knocked on doors to register voters in predominantly Latino neighborhoods in Los Angeles and Orange counties.

In 2016, Enamorado registered voters for the League of Latino Voters under the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project.

Coachella City Councilwoman Neftalia Galarza, Enamorado's former supervisor on the voter registration project, remembers that canvassers were paid by the hour and not by signature. But Enamorado always returned with droves of newly registered voters.

“Anyone who has done this type of campaign work knows it is not easy. You go to a stranger's house and ask for personal information,” Galarza said.

Over the years, he watched as Enamorado's brand of civic engagement blossomed into activism. Galarza believes that Enamorado is being an example by law enforcement who want to hold him responsible for his years as an activist.

“It should be worrying to all of us what is happening to Alex,” Galarza said.

Enamorado and the other activists will appear in court on Friday for another bail hearing.