After months of hearings, a federal judge ruled last month that the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs discriminates against homeless veterans whose disability compensation makes them ineligible for housing being built on its West Los Angeles campus.

U.S. District Judge David O. Carter previously ruled that the VA has a fiduciary duty to use the 388-acre campus primarily for housing and health care for disabled veterans, calling into question the legality of leases that have given away portions of it for sports facilities, oil drilling and two parking lots.

Neither ruling, however, gave any indication of what remedies, if any, the VA might face. That question will be up for debate in a bench trial that begins Tuesday in downtown federal court, the culmination of more than a decade of legal battles — and a half-century of grievances — over veterans’ land.

In a brief filed last month, attorneys for the veterans asked Carter to issue an order requiring the VA to provide nearly 4,000 units of permanent supportive housing on campus. That would be an increase of 2,740 units to the 1,215 already in planning or construction under the terms of an earlier lawsuit. They are also asking for the construction of 1,000 shelter beds.

They also ask the judge to prohibit the VA from contracting with developers whose funding sources impose restrictive income limits that prevent veterans with disability compensation from receiving compensation. If granted, such an order could have a national impact on VA housing construction that relies on outside developers.

The brief is less specific about leases for sports facilities, oil drilling facilities and parking at UCLA and the nearby Brentwood school. It asks Carter to declare the leases invalid, but does not say whether they should be voided or renegotiated to better serve veterans.

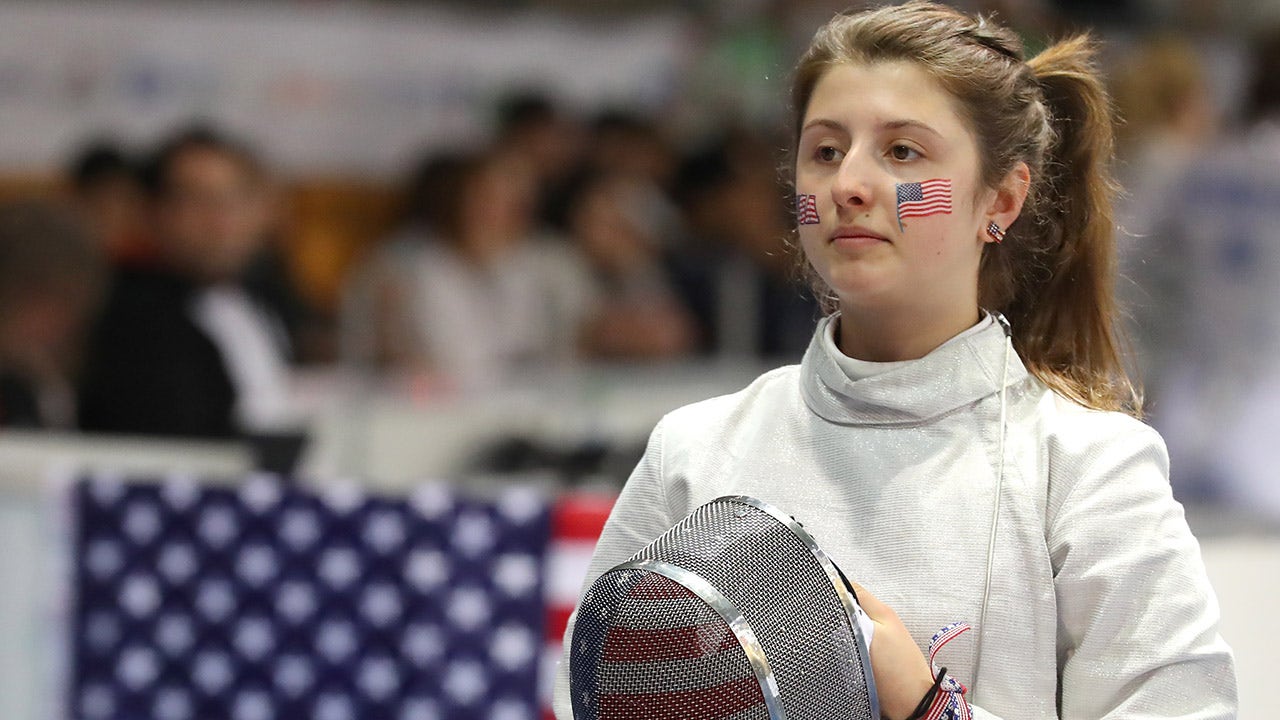

American flags decorate tents at a homeless veterans encampment along San Vicente Boulevard in Brentwood, California, on July 4, 2020.

(Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times)

Justice Department attorneys representing the VA argue in an opposition brief that Carter should not order additional housing or issue an injunction because the requested relief is unnecessary and unfeasible and would place an undue burden on the VA.

The lawsuit, filed last November by 14 veterans and later converted to a class-action suit, repeated an earlier lawsuit challenging leases and asserting an unmet need for permanent housing. In a 2015 settlement, the VA agreed to develop a master plan for the campus. A draft of the master plan, completed in 2016, called for 1,200 units of on-campus housing in new and rehabilitated buildings with a commitment to complete more than 770 units by the end of 2022. Only 54 of those units were completed by the deadline, and only 233 are currently open.

The new lawsuit, filed by Public Counsel, Inner City Law Center and law firms Brown Goldstein & Levy LLP and Robins Kaplan LLP, alleges that the VA has breached the settlement agreement.

The plaintiff's lead attorney, Mark Rosenbaum of Public Counsel, said at a hearing last year that the new case was necessary because he had erred in failing to require court oversight of the 2015 settlement.

“The phrase ‘homeless veteran’ should be an American oxymoron,” the complaint states. “But here’s the cruel truth: The federal government consistently refuses to keep its word and take meaningful action to end the abomination of homeless veterans.”

The housing controversy dates back to the Vietnam War era.

The West Los Angeles campus, formally called the Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, was established as a home for Civil War veterans on land donated in 1888 by Sen. John P. Jones and his business partner, socialite and businesswoman Arcadia Bandini Stearns of Baker, a scion of a land-owning family dating back to the mission era. After World War I, the campus “gradually evolved from institutional housing to medical care that enabled veterans to reintegrate into civilian society,” according to a history on the VA’s website.

By the early 20th century, as many as 4,000 veterans lived on the property, but the campus's transformation into a medical center continued after World War II, as advances in battlefield medical care resulted in higher survival rates for more severe injuries. By 1962, the West LA VA Medical Center was the largest in the country, with more than 6,000 patients and 4,500 employees.

But by the late 1960s, residential use declined. Then, following the 1971 Sylmar earthquake, the Wadsworth Hospital building was deemed seismically unstable and demolished. To make room for a temporary hospital during its rebuilding, the remaining 1,000 or so residents of the Old Soldiers Home were abruptly evacuated. Only about half moved to other VA facilities, and after the new hospital opened, the old buildings were allowed to deteriorate.

Carter ruled in December that the 1888 deed for 300 acres dedicated to “the establishment, construction and permanent maintenance of a branch of said National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers” created a charitable trust and that Congress, in adopting the West Los Angeles Lease Act of 2016, assumed enforceable fiduciary duties to use the land for the benefit of veterans.

In May, Carter certified the case as a class action representing all homeless veterans with severe mental illness or traumatic brain injuries residing in Los Angeles County and a subclass of all class members whose income (including veterans' disability benefits) exceeds 50% of the area median income.

Last month, Carter issued a partial summary judgment in favor of the veterans, finding that the VA discriminates against veterans whose disability compensation makes them ineligible for housing built by developers whose funding sources come with income limits.

“He who gave the most cannot receive the least,” he wrote.

In his pre-trial brief, Rosenbaum argued that the lack of adequate housing at the VA forces veterans with severe mental illness or traumatic brain injuries into institutionalization.

“Homeless veterans with severe mental illness and traumatic brain injuries who lack permanent supportive housing experience an institutional circuit of temporary housing, emergency departments, psychiatric facilities, and jails to receive health care services, including mental health care services,” he wrote.

To support their demand for more housing, the plaintiffs intend to present testimony from three prominent Los Angeles residents. Real estate developer and former police commissioner Steve Soboroff will testify that he has identified space on campus for an additional 4,000 units. Jonathan Sherin, former director of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, and Benjamin Henwood, director of the Center for Research on Housing, Health and Homelessness Equity at USC’s Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, will testify about the mental health impacts of homelessness.

The government’s opposition brief argued that the 2022 update to the master plan envisions a “caring and integrated community” with services, amenities, and recreational, cultural and open spaces.

The plaintiffs' lawsuit would impose an undue burden, the government argued, by requiring the VA to construct approximately 40 buildings, obtain new environmental reporting authorizations for historic preservation and extend public services to new areas of the campus.

She cited several improvements the VA has made to its services and changes to income requirements that make 97 percent of homeless veterans eligible for federal housing vouchers.

He also argued that housing a majority of veterans with severe mental illness or traumatic brain injuries on campus “would segregate them from the broader community and likely result in their stigmatization based on their disabilities.”

Carter has yet to rule on the validity of the leases, which set aside a limited time for veterans to use the sports facilities and generate revenue from oil and parking operations for VA operations.

Rosenbaum cited a 2021 report from the VA Office of the Inspector General that found that seven of the VA’s land use leases, including those for Brentwood School and oil and parking lot operators, were not in compliance with the West Los Angeles Lease Act and that seven and a half years after the previous agreement, no supportive housing had yet been completed.

Attorneys representing Bridgeland Resources LLC intervened in the case, filing a brief arguing that the 2017 lease under which the company uses a portion of VA property to drill in a West Los Angeles oil field complies with the West Los Angeles Lease Act because it provides a 2.5 percent royalty to the Los Angeles Chapter of the Disabled American Veterans “solely for the purpose of providing transportation to veterans on and around the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System campus.” If that lease were invalidated, they said, prior leases would go into effect, allowing Bridgeland to expand its operation.

Rosenbaum said those prior leases would also be invalid.

Neither UCLA nor the Brentwood School have sent lawyers into the courtroom or attempted to intervene. Spokespeople for UCLA and the Brentwood School declined to comment.

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this article.