When Danielle Ipiña-Vigil, a member of the Yurok tribe, disappeared in San Francisco last summer, her family requested that state police issue a Plume Alert, an emergency notification intended to help authorities locate missing indigenous people in California.

But the request was denied, making Ipiña-Vigil one of three known cases of Native people living in California who went missing in the last year and for whom a Feather Alert application was dismissed. Since the system began a year ago, authorities have issued only two of the five requested Plume Alerts, according to the California Highway Patrol.

A CHP official said local officers denied the requests because they did not meet criteria, which include that the person went missing under suspicious circumstances and that officials believe they are in danger.

But the denials have fueled concern in native communities that the system meant to help locate missing indigenous people is not working as expected.

“We have had two successful Feather Alerts and numerous negative ones,” Taralyn Ipiña said while talking about her sister Danielle, who disappeared in June, during a somber news conference Wednesday. She was later found and details about her case are limited. “Being denied a Pen Alert based on opinions contradicts the very basis of [this] legislation.”

Now Sacramento policymakers are reevaluating how well the law is working. More than a dozen California tribal members gathered at the Capitol last week demanding information about three missing persons alerts that were denied. They also call for eliminating a statute that requires local law enforcement to act as a buffer between tribes and the CHP and instead opening the door for state and tribal police to work together.

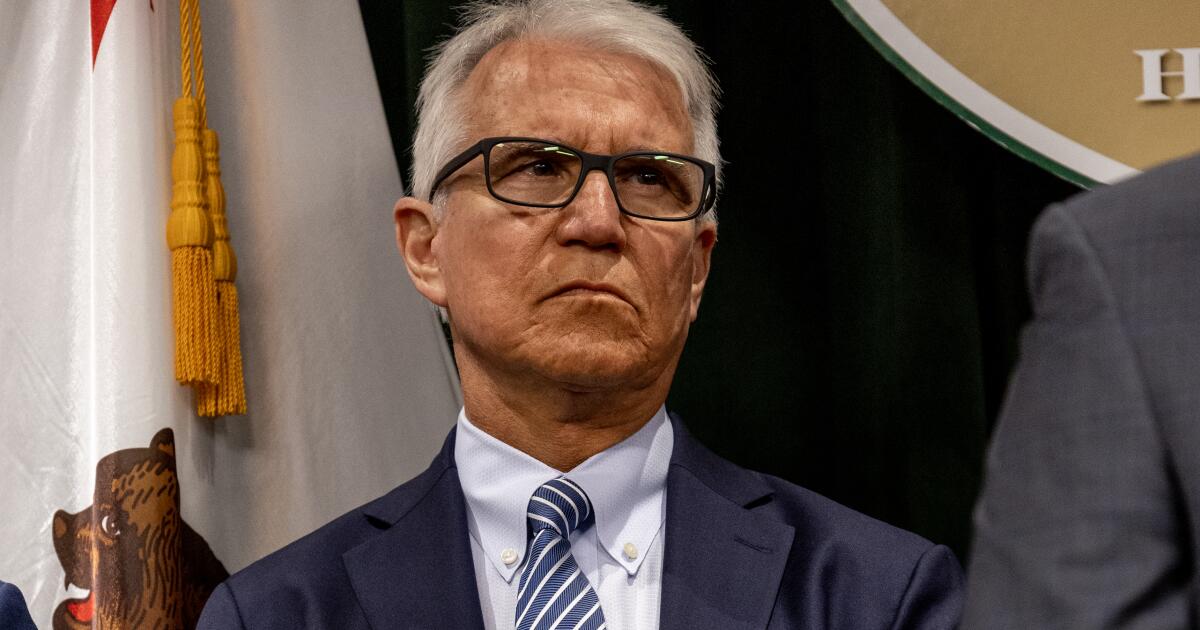

“The alert must be issued by CHP as structured. But the middleman is the local law enforcement agency that the request comes to,” said CHP Commissioner Sean Duryee, who testified at the hearing. “Some are doing really well. What has been expressed to us is that sometimes that intermediary creates problems for tribal communities.”

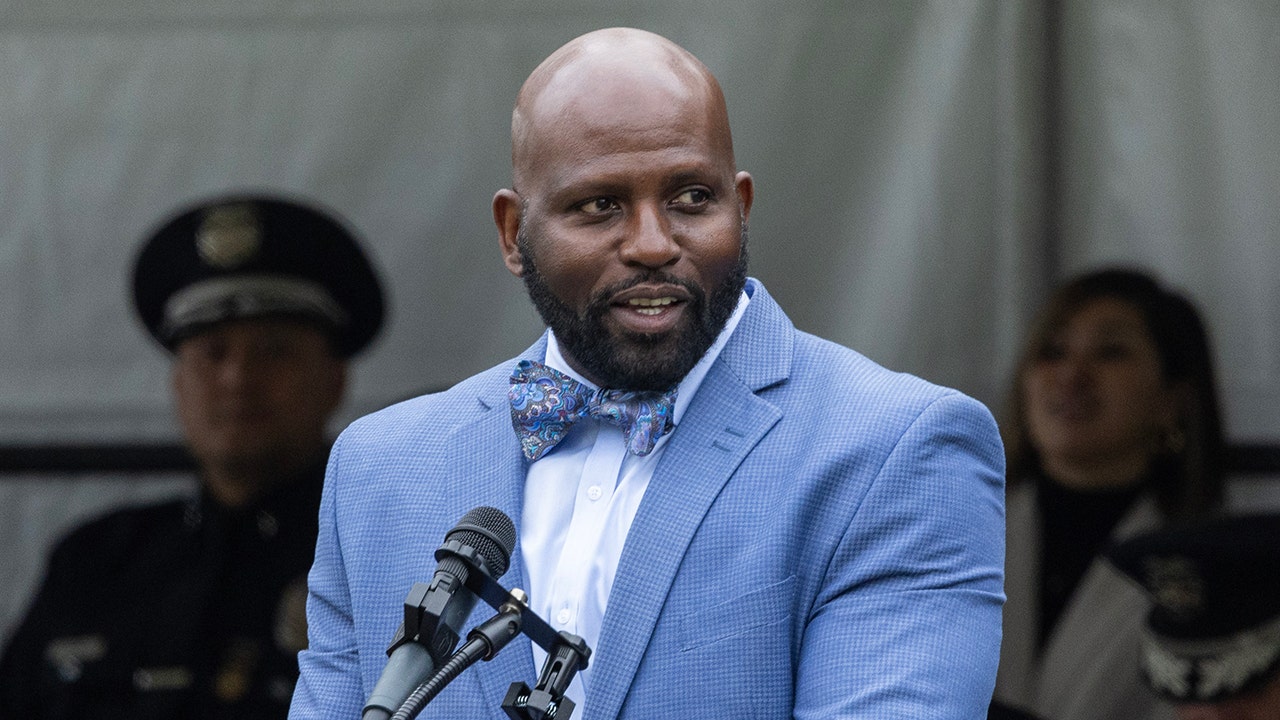

The Feather Alert, enacted in 2022, was designed to be similar to the Amber Alert, which since its creation in 1996 has located more than 1,100 missing children nationwide. Assemblyman James Ramos (D-Highland), who was California's first Native American elected to the Legislature, argued that the state needed a separate system for missing indigenous peoples because of high rates of violence and kidnappings in tribal communities. It is one of seven categories of missing persons alerts in California.

New data shows that the CHP approved all six of the Amber Alert requests it received the same year it rejected three of the Feather Alert requests.

Leaders and members of tribes from across the state, including the Yurok and Me-wuk, arrived early at the Capitol calling for clarity on those requirements and for missing person reports to be addressed urgently.

“We can't get caught in the middle of the California Highway Patrol and the tribe,” said Chairman Joe James of the Yurok Tribe, which lives near the lower Klamath River. “Why were they denied?”

There are 151 active cases of missing American Indian/Alaskan Natives in California. At least one of the denied Feather Alerts came from Humboldt County, which currently has the highest number of cases.

Duryee did not go into detail during the hearing about the denied cases, citing privacy laws, but said the officer who responded to the requests “did not feel the criteria were met.”

Tribal members said these denials recall historical trauma tied to decades of unreported missing and murdered persons cases — the reason Feather Alert was created in the first place.

“There are many factors that determine whether they are missing,” Duryee said. “Just because someone doesn't qualify for Feather Alert doesn't mean we wash our hands of it.”

Duryee said law enforcement agencies still have the power to do “traditional police work,” such as using license plate recognition or cell phone data. “Just because an alert isn't issued doesn't mean authorities aren't working on it,” he said.

During the emotional hours-long hearing before the Assembly Select Committee on Native American AffairsIndigenous people expressed distrust in the state system for reporting crimes and missing persons.

Merri López-Keifer, director of Native Affairs at the California Department of Justice, testified that her team is reevaluating data on crimes against tribal members, citing possible “misidentification” of race and “underreporting.” She said missing persons reports allow only one racial category to be selected, which does not take into account the “vast landscape and regional variations” across the state.

“This approach may miss potential cases involving multiracial people,” López-Keifer said. “It is especially relevant in the context of American Indians/Alaska Natives, who are often racially misclassified as white, Hispanic, or Asian.”

“We don't necessarily know the number, it's the truth,” he said.

Tribal communities are calling for amendments to the law, including allowing tribal law enforcement to issue Plume Alerts. Ramos said he plans to propose legislation in the coming weeks.

“Today's hearing was intended to bring ideas to light,” he told The Times. “And now we will get to work.”