In recent years, the Los Angeles Unified School District, the Los Angeles County Office of Education, and the state of California have reaffirmed their commitment to climate education for all students, from preschool through 12th grade. In October, Governor Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 285, require climate education for all public school students beginning in the 2024-25 school year.

Los Angeles-area public schools are now guided by the most ambitious climate education policies in the country, according to local school administrators and environmental education advocates.

The problem is that there isn't much extra money for all this.

Tired of waiting for politicians to step in with funding, some professors are investing personal time and talent to create their own climate lessons and raise funds for green initiatives on their campuses.

1

2

3

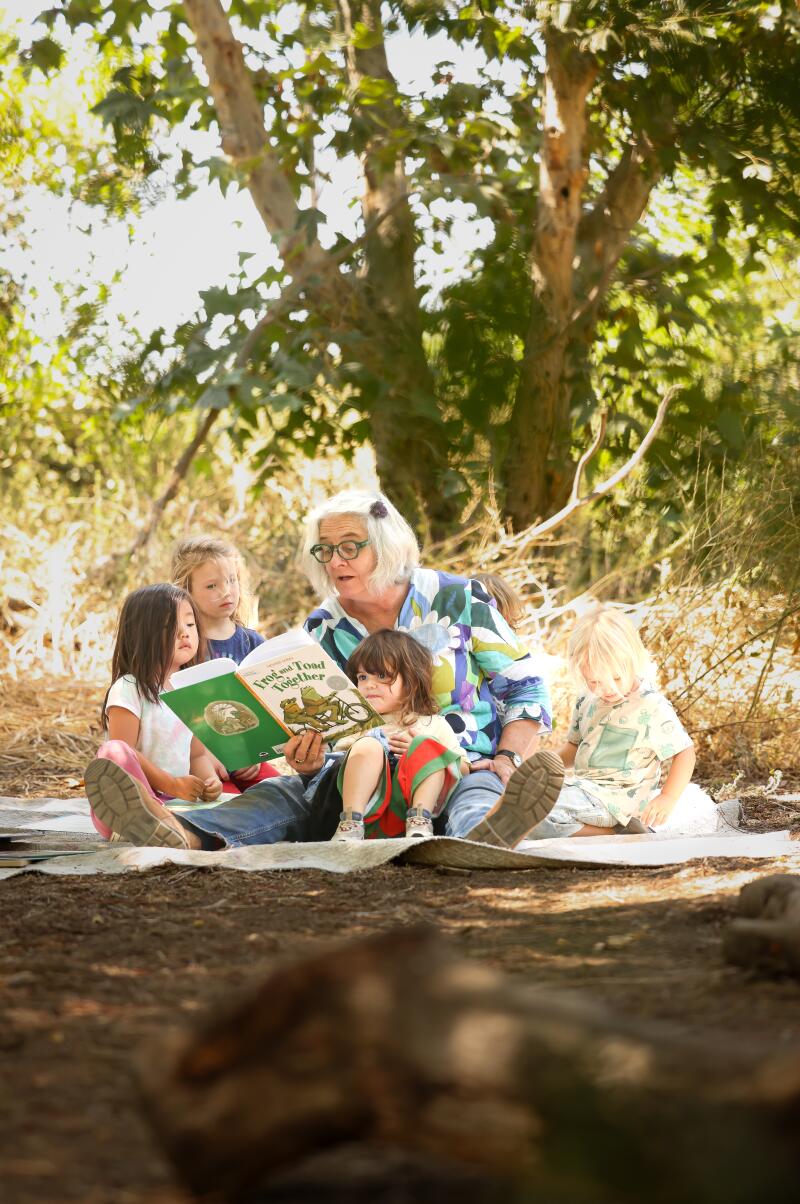

1. Angela Capps leads kindergarten students on a hike at Earthroots Field School in Silverado Canyon. (Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times) 2. Teacher Arturo Romo shows student Jason Aviles, 17, how to harvest basket material in a native habitat area at Sotomayor Arts & Sciences Magnet. (Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times) 3. Fabienne Hadorn, co-founder of Arroyo Nature School, reads to children in South Pasadena. (Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

In the Los Angeles Unified School District, these teachers are often chosen as “climate champions.” Principals at each of the district’s roughly 1,220 schools must choose a teacher who will receive $900 per semester to help other educators on their campus create climate-focused classes.

An LAUSD statement reads: “Through school-wide Climate Literacy Champions and all classes, including science, students learn about climate change by addressing real-world issues related to the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals.”

The “champions” meet regularly to support each other, share ideas and work with their principals to encourage other teachers to join the effort. But some of them say it’s an overwhelming responsibility, adding to an already heavy workload and can lead to burnout.

The implementation of the climate literacy policy “has been uneven,” said Lucy Garcia, a former LAUSD teacher who was one of the primary authors of the resolution. “Nothing happened the first year. The second year they only trained 145 champions. We need to get it done faster in the classrooms.” There are currently a total of 314 champions.

Frances Baez, the district’s chief academic officer, said there is “universal support for climate literacy” in LAUSD, adding: “We don’t have the funding to reach the scale that we all want to achieve.”

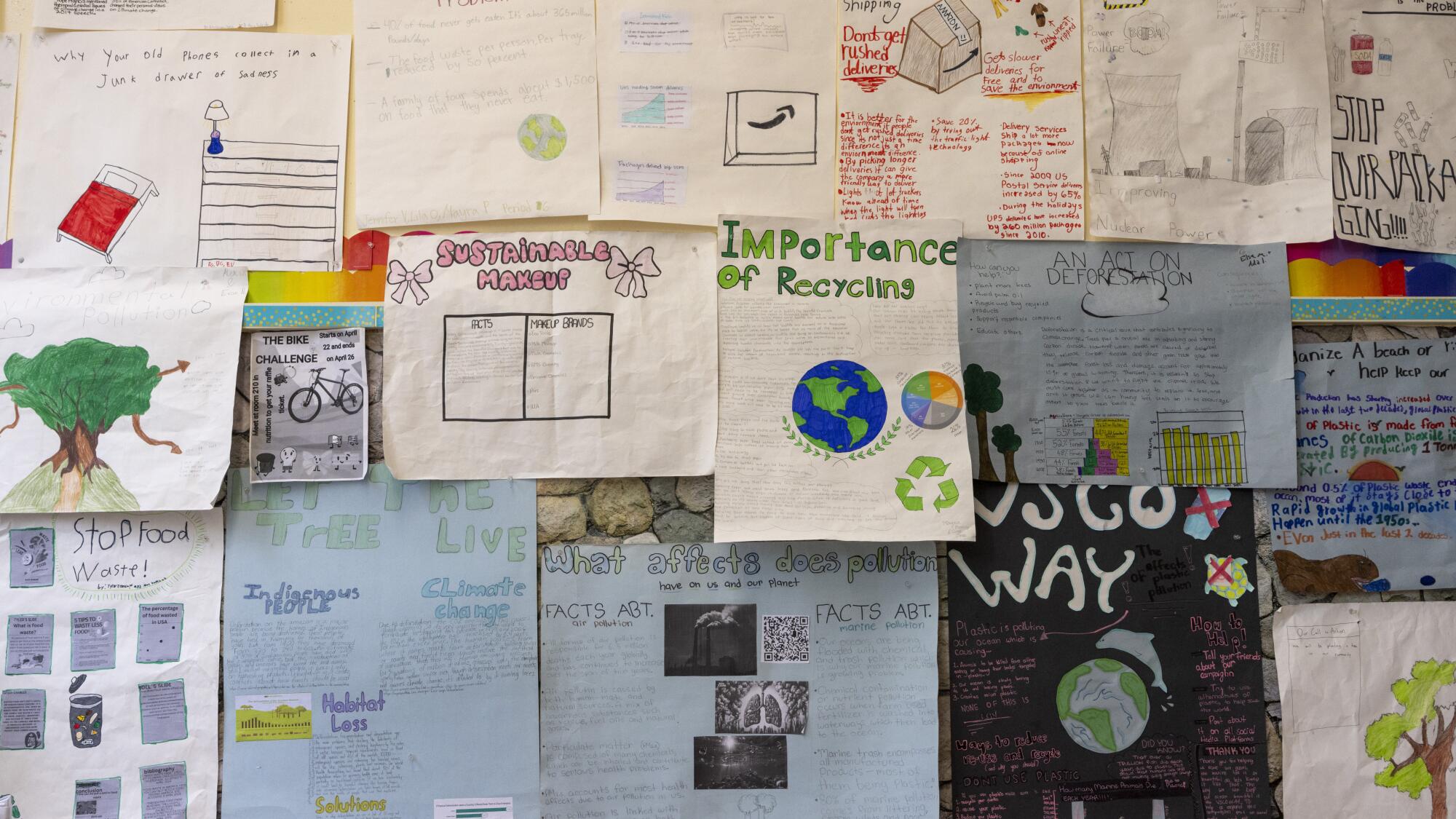

A classroom wall at Mark Twain High School is dominated by environmental concerns.

(Zoe Cranfill/Los Angeles Times)

Baez encourages teachers to seek support from nonprofit education funders. One of her favorites is Esports for goodwhich offers a Minecraft-like video game based on the United Nations’ sustainability goals. Students create virtual solutions to real-world climate problems.

Individual schools have found support for climate programs from private foundations and federal and state grants.

One of the leading non-profit organisations in this field, Ten Strands, is the force behind the California Environmental Literacy Initiative, a centralized effort to pressure state and local education leaders to live up to their commitments.

The network of educators, public school administrators, local and state agencies, and nonprofit partners provide resources, curriculum, and professional support to each other. “Everyone doing this work in the state is singing the same song as one chorus,” said Andra Yeghoian, project director of the initiative and 'Ten strands' Director of Innovation.

“Climate literacy is not taught in isolation, it’s not taught every day or all day long,” Baez said, adding that the goal is to integrate it into all learning. “We’re definitely not where we want to be, but we’re getting there.”

When it comes to green energy technology on campus, the potential for change is much more promising. It's an area with a lot of federal funding available through the Inflation Reduction Act.

Federal rebates can cover 30% to 50% of the cost of solar power, energy storage technology and high-efficiency heat pumps. Grants and further rebates are available for electrifying school bus fleets and installing charging stations.

Students plant green onions, basil and kale in the garden at 24th Street Elementary School in Los Angeles.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

“The new federal money to improve the climate resilience of our schools is real and meaningful,” said Jonathan Klein, co-founder and CEO of UndauntedK12, a national advocate for sustainable and healthy schools.

LAUSD’s Chief Eco-Sustainability Officer Christos Chrysiliou is in charge of leveraging these dollars to meet the district’s commitment to shift to 100% clean electricity by 2030 and clean energy across all sectors, including transportation, by 2040.

One sign that Los Angeles should benefit from this program was Chrysiliou’s appearance on stage at the White House conference last spring, touting President Biden’s investments in sustainable schools.

Two more potential new sources of money to improve climate education and school infrastructure (gardens, outdoor learning spaces and other facility improvements) will be on the November ballot in California.

Proposition 2 would authorize the state to borrow $10 billion to build and modernize school facilities, and Proposition 4 would authorize the state to borrow $10 billion for climate programs, including clean water, wildfire, forest and sea level rise projects.

The proposals are real progress, said Mikaela Randolph, who heads the Southern California Leadership Institute of the non-profit organization America's Green SchoolyardsThe goal is to expand tree canopies to cover at least 30 percent of all school campuses in the country, enough to reduce campus temperatures, according to the group's research.

“Funding to advance this work is an opportunity to rethink our schools,” Randolph said, allowing for outdoor learning while protecting students from the effects of climate change.

Children learn about the environment at a camp run by Earthroots Field School in Silverado Canyon. Many educators enjoy teaching their environmental classes outdoors.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times)

Chrysiliou said she can't wait to receive the funding and is moving forward to develop a “roadmap” for climate literacy education and engagement, construction, operations and maintenance that embraces social equity and inclusion.

“Outdoor learning is extremely important,” she said. “Research shows that students can learn a lot from nature. We are looking to develop spaces that are more engaging and exciting for our students.”

“Our students are very interested in climate change. Our cities have been transformed into urban environments of asphalt and concrete. Our students don’t want that in their schools. They are eager to learn about agriculture, about plants, to experience nature at school,” she said.

Our challenge in the face of climate change

Creating your own resume

California wants its students to receive climate education. Meet some of the teachers, schools and nonprofits that are making it possible.