Mike Juma sat at the end of his bed in his ninth-floor one-bedroom apartment in downtown Los Angeles, looking out at the mountains visible from his window.

“I don’t like tall buildings,” he said. “But look at that wonderful view. That’s what they call a million-dollar view.”

A year ago, Juma, 64, found himself in a very different place in his life. He was living in a tent on Skid Row, selling cigarettes to make money and sleeping with a samurai-style sword at his side for protection.

Now, you are in a furnished apartment listening to the soft sound of the air conditioning.

Juma is part of a wave of homeless people who have moved from Skid Row into temporary and permanent housing over the past year. It’s all part of a $280 million county initiative to house more than 2,500 people, boosting health, drug treatment and related services in the 50-block neighborhood that has become synonymous with poverty and homelessness.

Mike Juma shows off his kitchen at the Weingart Tower in downtown Los Angeles, where he moved in early August.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

The initiative, called the Skid Row Action Plan, is also an effort to counter the systemic racism that has driven people to Skid Row, where disproportionate numbers of Black people fill sidewalks and encampments, by trying to transform the neighborhood into a thriving community.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district includes Skid Row, initiated the project, which got underway a year ago after months of planning and organizing. So far, the county has moved nearly 1,000 homeless people into permanent housing and nearly 2,000 into interim housing, such as shelters and transitional housing, according to data recently released by the county’s Housing for Health program, which is leading the project.

At the time of the project’s launch, 4,402 people were experiencing homelessness on Skid Row, with more than half living in tents or makeshift shelters, according to the 2022 Los Angeles Metropolitan Area Homeless Census. Today, the population is 3,791, a decrease of nearly 14%.

“We’re very focused on this,” said Elizabeth Boyce, deputy director of Housing for Health. “We’re sticking to the core components of solving homelessness and the things we know we can do.”

The progress comes at a time when counties and cities are facing pressure from Governor Gavin Newsom to clear homeless camps following a Supreme Court ruling that such cities can enforce laws restricting homeless encampments on sidewalks and other public property. Adding to the pressure is the upcoming 2028 Olympics.

Solis praised the agency and its partners for the quick response.

“With a goal of permanently housing 2,500 people in three years, one year after the program was initiated, we have achieved more than a third of the goal,” Solis said in an email. “The crisis we have on Skid Row has been brewing for years and we must all work together to address it by focusing on prevention, early intervention and access to evidence-based treatment services.”

Government officials have long sought to address the homeless problem in Skid Row. In the early 1970s, for example, developers wanted to demolish much of the area, while others advocated preserving the neighborhood’s low-income housing and services as a way to keep people on Skid Row — what became known as the “containment plan.”

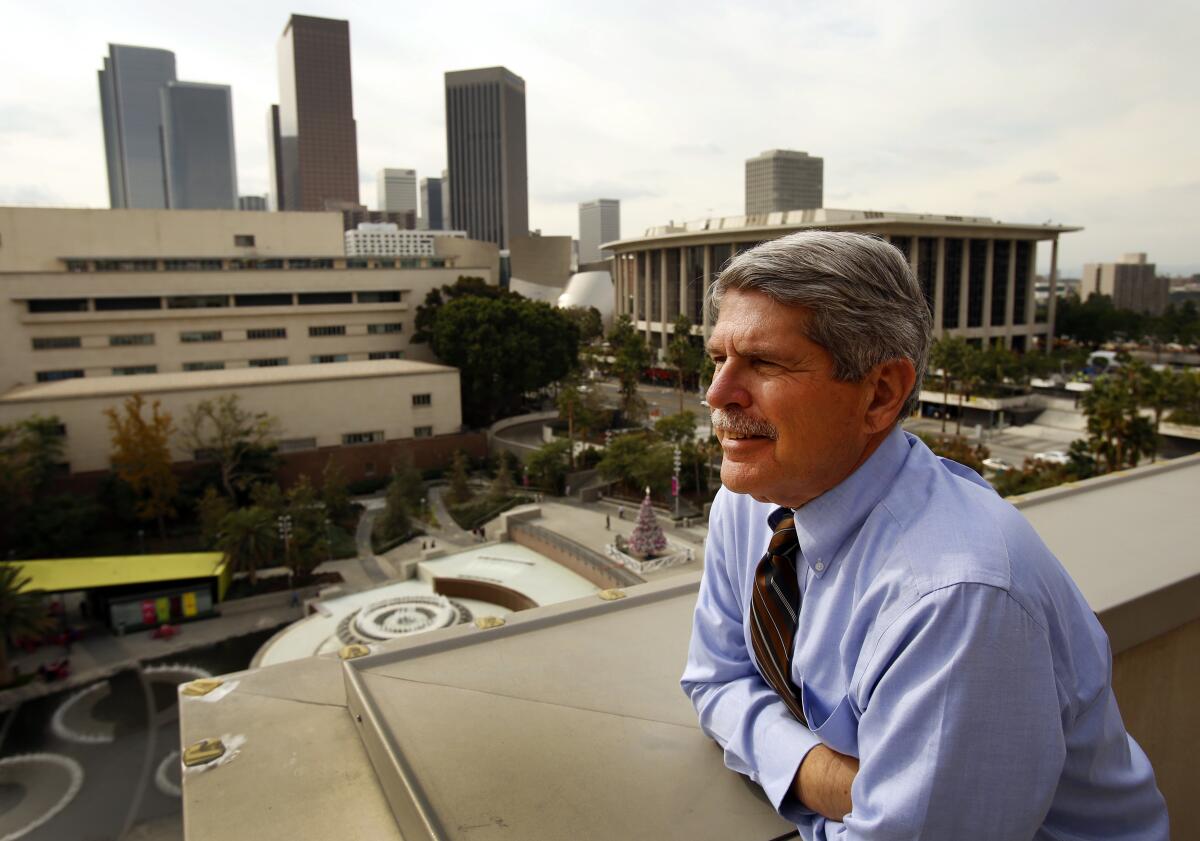

Zev Yaroslavsky in downtown Los Angeles in 2014. As a county supervisor, Yaroslavsky launched Project 50 to help people who were chronically homeless.

(Al Seib/Los Angeles Times)

In 2007, then supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky launched Project 50a pilot program aimed at housing 50 of Skid Row's most chronically homeless people through a housing-first approach. He attempted to scale it up, but was unsuccessful. failed.

Boyce said what makes the Skid Row Action Plan unique is that it was designed to address the neighborhood’s complex needs with the help of Skid Row residents, service providers and other stakeholders. It also leverages resources the county is already using to address the homelessness crisis in the region.

“We were really thinking from the beginning,” she said, “how do we create thoughtful, compelling change… not by changing the people who live there but by changing the support that people receive.

“You have to get some early wins and show that you are talking business.”

In June 2023, the project received a major financial boost when Housing for Health and its partners, the City of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, received a $60 million state grant to finance the project until 2026.

Boyce said the funding was crucial to the project's initial success. It helped create 350 new interim housing units and 750 new permanent units, and increased and improved outreach services.

The funds have also helped establish a “safe landing” in the lobby of the Cecil Hotel; people can come in at any time of day or night to receive health services and housing. The money also created a program to specifically help Skid Row providers access interim housing for clients as quickly as possible.

County officials say their work is far from over. They plan to create resident advisory councils that will oversee key areas of the Skid Row Action Plan. Additionally, they hope to build a Harm Reduction Health Center to provide drug testing and detox beds and provide referrals to rehabilitation centers, among other services. There are also plans to establish a safe site zone — a large outdoor park on Skid Row where people can visit and interact with various agencies to access government benefits and programs.

Juma looks out at the view from his room on the ninth floor of the Weingart Tower 1.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Last week, on the ninth floor of the Weingart Tower, Juma lit a cigarette.

“It's like getting used to the smell of a new car,” he said of his new home, his voice hoarse. “It's different.”

Juma's tower is located on Skid Row and includes 228 studios and 47 one-bedroom apartments. At least 40 units are reserved for veterans. Juma served in the Navy.

It is unclear how Juma ended up on the streets. He said he previously had a business transporting fish around the country. He had financial and tax problems and eventually lost the business and everything that came with having a stable job.

Drinking was part of the story, though he says it was not a factor.

When he became homeless, he said he returned to an area he knew. He set up a tent near 6th Street and Towne Avenue, not far from the seafood businesses.

He said he grew accustomed to living outdoors, even though it was sometimes tough. At night, he rarely slept amidst the screaming, loud music and fights. Plus, there was the early morning traffic of commercial trucks.

“You hear everything,” he said. “You’re like a blind man, you hear footsteps, you can’t sleep.”

Last year, he said he was ready to get off the streets after injuring a man during a fight. Standing over the bleeding man, he said, he knew he was done.

“I almost killed him,” he said. “I’ve had many fights; sometimes you come out on top, but you never really win.”

He then contacted social workers at Housing for Health, who quickly found him a temporary place to stay. He then applied for supported housing and waited several months. A week ago, he was told an apartment was available for him.

Mike Juma, who served in the Marines, has a new place to call home on Skid Row.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

He said he had spent the three days since he moved into his new apartment sleeping. Behind him on the bed was a brown pillow with the inscription: “God has not forgotten me.”

Juma said the apartment came with a new refrigerator, a stove, a television and, thankfully, a bathroom. He said the kitchen cabinets were filled with dishes, pots and cooking utensils.

But the window is the most symbolic element of his new home. As he considers the possibilities that await him, he can glimpse his past life. High above his room, he says, he can make out the street where he lived in a tent.

Sometimes, he says, he looks down and thinks, “Things worked out okay in the end.”