Editor’s note: This CNN Travel series is, or was, sponsored by the country it highlights. CNN retains full editorial control over the subject matter, reporting and frequency of sponsored articles and videos, in accordance with our policy.

cnn

—

In one of the most rapidly developing countries in the world, there is a monument carved from sandstone, surrounded by date plantations and dusty two-lane roads.

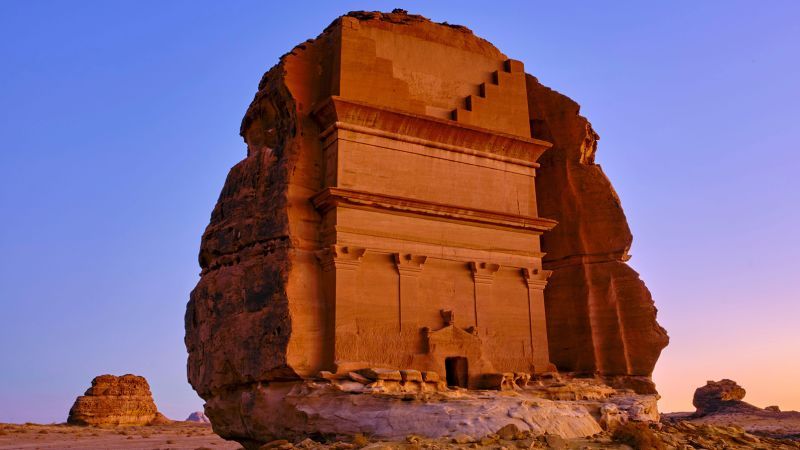

This is Hegra.

Also known as al-Hijr or Mada’in Saleh, Hegra is the crown jewel of Saudi Arabia’s archaeological attractions and was the country’s first site inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Built between the 1st century BC. C. and the 1st century AD. C., this ancient city includes an impressive necropolis, with tombs carved from sandstone set against the wide desert landscape of northwestern Saudi Arabia.

Petra, Jordan’s famous site, was the capital of the Nabataean people, while Hegra was the kingdom’s southern outpost until it was abandoned in the 12th century.

But while Petra is one of the seven wonders of the modern world and welcomed more than a million visitors a year before the pandemic, Hegra has only been accessible to most international visitors since 2019, when Saudi Arabia began broadcasting tourist visas.

Although Hegra still does not have the same widespread recognition, that is changing thanks to AlUla, the nearby oasis city that has become an arts, cultural and tourist center and now has a small but well-connected airport, with regular flights from Jeddah. , Riyadh and Dubai.

Out of the shadows of history

The Nabataeans are believed to have traded aromatic products, such as incense and spices, many of which were used in religious rituals.

Two of them were frankincense and myrrh, which many Westerners will recognize as gifts given to the baby Jesus in the Christian Bible.

But most of their culture has been lost to history. Now, increased investment in archeology by the Saudi government means more and more information is coming out of Hegra and other Nabataean sites.

“We’ve all heard of the Assyrians, we’ve all heard of the Mesopotamians,” says Wayne Bowen, a history professor at the University of Central Florida. “But (the Nabataeans) faced the Romans, they faced the Hellenistic Greeks, they had this incredible cistern system in the desert and they controlled the trade routes. “I think they just become absorbed in the story of the growth of the Roman Empire.”

Although the Nabataeans did not leave much historical documentation, one of the achievements of their culture continues to play a very important role in the region: the Nabataean alphabet laid the foundation for modern Arabic.

Recently, some historians literally put a face to the Nabataeans.

In early 2023, they revealed “Hinat,” the reconstructed face of a Nabataean woman whose remains were found in the desert. Now travelers can see it at the Hegra visitor center.

On the sandy ground

Upon arrival at the visitor center, guests are greeted with dates and cups of Saudi coffee, which is brewed very lightly and often mixed with cardamom. It is poured into a traditional silver urn with a curved spout.

From there, they can hop into a vintage, mid-century-style Land Rover (with or without a roof, depending on the weather) with a guide and head out to explore.

Like many places in this sun-drenched part of the world, AlUla and the surrounding region are best visited early in the morning or in the evening. This is even more true in Hegra, which has no trees or structures to block the scorching midday sun.

The Nabataeans were a nomadic people, so not much remains of their daily life. However, what remains are their incredible final resting places.

In total, there are around 115 known and numbered tombs.

The most famous of these is Qasr al-Farid (Arabic for “the lonely castle”), which stands proud and alone, its 72-foot structure dramatically contrasted with an expanse of sand. The contrast makes it a great backdrop for photographs, especially just before sunset when the pinkish-orange light highlights the desert tones.

One tomb at a time is open to visitors who want to take a look inside. These open graves are rotated so that no one gets too much foot traffic.

However, they are much more complex and interesting on the outside.

The area around door frames may show the names of people buried there. Details of the design give clues to where residents may have traveled from. Images of phoenixes, eagles, and snakes imply familiarity with cultures as far away as Greece and Egypt.

Broaden your search

Many visitors combine their trip to Hegra with visits to the smaller nearby historical sites of Dadan and Jabal Ikmah.

In the Jabal Ikmah Valley, which the Saudis call an “open-air library,” you can see a series of inscriptions carved in Aramaic, Dadanitic, Tammudic, Minaic and Nabataean, all of which provide glimpses of information about the rich history of this region. Translations are shown in Arabic, English, and sometimes French, as French monks were the first visitors to the area.

Dadan, meanwhile, was once home to an important pre-Islamic trading city, where spice sellers mingled with religious pilgrims.

Its most notable site is the “Tombs of the Lions,” a group of mausoleums decorated, as its name suggests, with carvings of lions.

It is easy to visit these three sites in a single day. The easiest way to book is through the website of the area’s official government tourism body, Experience AlUla. Travelers in a hurry can book a two-hour tour, but there are also day or afternoon options.

Don’t miss the covered outdoor station near the Hegra visitor center, where you can practice using a small chisel to carve your name or initials into pieces of stone.

The amount of effort involved will make you truly appreciate how much work the Nabataeans put into creating these masterpieces. Also available for sale are miniature versions of Hegra’s most magnificent structures, made by the women who run this workshop.

Currently, Petra is focused on preservation and combating overtourism, giving Hegra the opportunity to grow and attract more visitors.

According to David Graf, professor emeritus of Middle Eastern history at the University of Miami, many of the archaeologists who previously led the excavations at Petra are moving to Saudi Arabia, which likely means there will be new discoveries in the coming years.

It also means that more people around the world will learn about the Nabataeans and their contributions to history.

“The Nabataeans were a very cosmopolitan and sophisticated culture, and I’ve been trying to emphasize that,” says Graf, who continues to publish articles and give talks in his retirement.

“We didn’t know much about the Nabataeans. I’ve been on a mission to see that we know more about them. “That we do not see them as backward and primitive people, but as truly committed, involved and dynamic people who interacted with Rome, the Greek world and other cultures.”