Los Angeles doesn't have a municipal Hall of Fame honoring illustrious natives and residents. Neither does New York. Nor does Chicago. Nor does any of the larger cities and counties in the United States…

Except Orange County!

Established last year by the Board of Supervisors, the Orange County Hall of Fame seeks to “honor the brilliant minds, influential leaders and remarkable talents who have shaped the cultural, economic and social fabric” of the county.

Each of the five county supervisors nominates five individuals and sends them to an ad hoc committee that makes the final selections. A ceremony for the new class of Hall of Fame inductees will be held in the coming months, and a permanent exhibit may be placed in a county building.

The best halls of fame — whether it’s baseball’s in Cooperstown, the California Museum in Sacramento dedicated to Golden State luminaries or the National Cleveland-Style Polka Hall of Fame (which is actually in Euclid, Ohio) — select people who exemplify the profession, place or era they honor. They don’t just honor pioneers and greats of yesteryear: They elevate the forgotten, address the controversial and display a worldview to present to, well, the world.

The Orange County Hall of Fame is nothing of the sort.

It seems like an absurd stance, not worthy of the sixth most populous county in the country. But then again, I'm giving my beloved homeland too much credit. For decades, those in power have told a very specific narrative about us: triumphalist and trivial, self-congratulatory and maudlin, but staying away from our difficult parts.

The Orange County Hall of Fame continues this sad tradition. So far, it seems like a nod to political favorites, fan posturing and history made through Google and Wikipedia searches.

Seven of the top ten included were artists or athletes, for heaven's sake, while the other three were developers.

The class of 2024 is better than the first, but most of its members aren’t as influential in the broader history of Orange County. Nick Berardino was the longtime head of the Orange County Employees Association, the county’s largest public employee union. Carl Karcher founded Carl’s Jr., the once-good burger chain that last year tore down its longtime headquarters in Anaheim after moving all its operations to Tennessee. Richard Nixon, who was born in Yorba Linda, attended Fullerton High, had his first law firm in La Habra and summered in San Clemente during his presidency, might seem like an obvious choice. But that was the extent of his life in Orange County, and there are far more important Republicans in creating Orange County’s peculiar brand of conservatism.

Wing Lam? His Wahoo's Fish Tacos chain isn't bad and his philanthropy is great, but Glen Bell, the founder of Irvine-based Taco Bell, had far more influence on Mexican food in Orange County and beyond. Michelle Pfeiffer, who grew up in unincorporated Midway City? Great performer, but come on, the choice should have been John Wayne, considered so essential to who we are by an older generation of Orange County residents that our airport is named after him.

Gwen Stefani attends a ceremony to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2023. The Anaheim native was also inducted into the Orange County Hall of Fame last year.

(Chris Pizzello/Invision/AP)

Frankly, the Orange County Hall of Fame shouldn't exist, but since it's probably not going away, it should at least try to do better, and that's not hard.

Take the inaugural class of 2023, for example. Kobe Bryant lived most of his adult life in Newport Coast, but his global fame came when he represented Los Angeles as a player for the Lakers. The late William Lyon was a prominent real estate developer, yes, but far more central to Orange County is his contemporary, Don Bren, whose Irvine County spans the county’s eras from ranch days to planned suburbs. His idea of what Orange County should look like is imitated around the world, for better or worse.

Or consider Greg Louganis, perhaps the greatest Olympic diver of all time, who learned his trade across the county. You know who would be a better choice? His coach, Sammy Lee, a two-time gold medalist and Korean War veteran. Lee made national news in 1954 when he tried to buy a house in Garden Grove but was denied because he was Korean-American. Instead, he settled in Santa Ana and had a decades-long career as a beloved community doctor and also an elite diving coach.

I don’t want to seem like an enemy. As a native who never plans to leave, unlike 2023 Hall of Famers Gwen Stefani and Tiger Woods, I’ve made OC history a central part of my adult life. I’ve written a book on the topic, co-written another, taught a course on OC Latino at Chapman University, and covered it throughout my career as a journalist. I’ve learned that knowing your hometown’s past and the stories of the people who made it possible allows communities to better face their present and future.

I’m not the only skeptic about the Orange County Hall of Fame. Supervisor Vicente Sarmiento — who as mayor of Santa Ana urged the city to formally apologize for its role in the 1906 Chinatown fire — didn’t bother to put forward any names last year.

“I thought, ‘Is this something worth our time and attention?’” she told me.

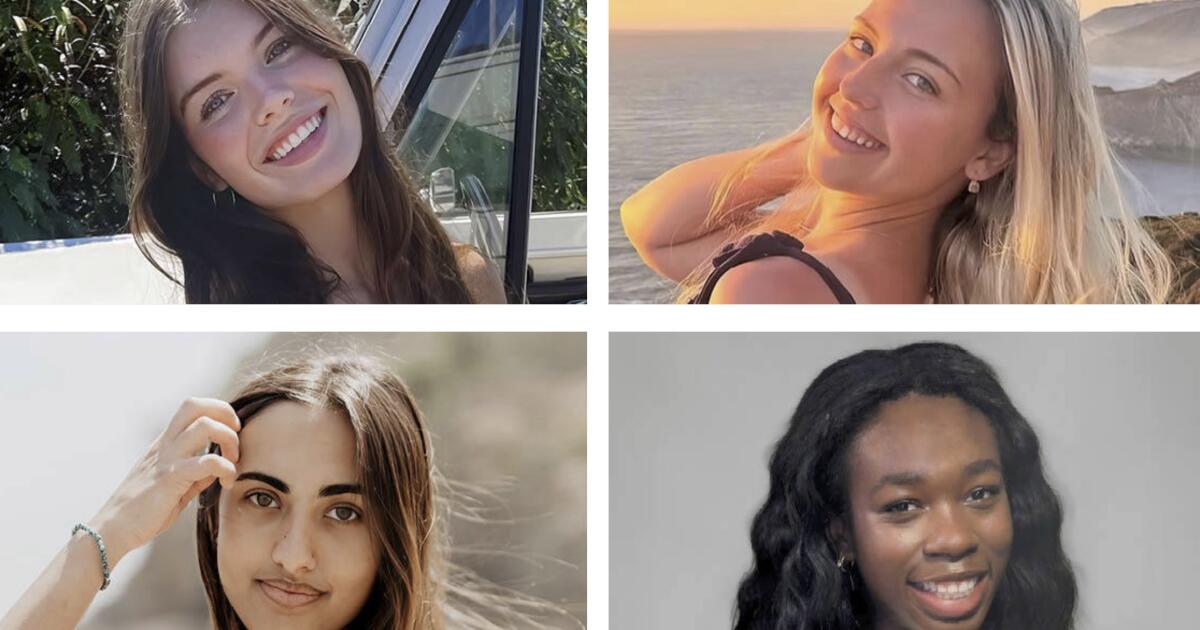

Sylvia Mendez visits with students in 2022 at Mendez Middle School, named after her parents, Felicita and Gonzales Mendez, who were part of a landmark school desegregation case. Sylvia was announced as an inductee into the Orange County Hall of Fame this month.

(Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times)

But the supervisor made nominations for the class of 2024 once he realized most of his colleagues were sticking with it. He decided to choose Orange County residents who offer “a different story from a different perspective.”

“If done right, this could show the evolution of where we came from,” he said.

One of their picks was Sylvia Mendez, who has spent decades publicizing the landmark 1940s school desegregation case that bears her family’s name. The ad hoc committee — comprised this year of Supervisors Don Wagner and Doug Chaffee — accepted Mendez but rejected the four other Latino families who were co-plaintiffs.

The committee also rejected the case of Dorothy Mulkey, a Santa Ana resident who in 1967 won a Supreme Court case over a California proposition that allowed landlords to discriminate against tenants.

“I’m going to run again next year and every year until she wins,” Sarmiento said of Mulkey. “Those are the kind of people I would like to see celebrated and recognized.”