Crouched in front of a Xerox machine in an advertising agency above a flower shop on Melrose Avenue, Daniel Ellsberg began the laborious process of photocopying the smuggled documents he hoped would end the Vietnam War.

That same day in October 1969, he had opened the safe in his office at Rand in Santa Monica, where he worked as an analyst, and removed the first batch of top-secret documents. He had walked past the lobby guards with his briefcase, waving casually.

“I assumed that what I was doing violated some law,” Ellsberg wrote in his 2002 book “Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers.”

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, from the momentous to the obscure, delving into the archives and memories of those who were there.

His conscience had been gnawing at him for years. He had been a Marine, a staunch Cold War supporter and a Pentagon consultant who advised the architects of the Vietnam War, accepting the premise that it could thwart a Stalinist dictatorship and promote democracy.

By age 38, he had become disillusioned with what he called a “hopeless and endless” war, built—as he hoped the public would understand through the newspapers—on decades of lies.

These were 47 volumes, comprising 7,000 pages, documenting American military decisions over two decades. They demonstrated that optimistic discourses about the war concealed much more sombre assessments behind the scenes, and that protecting American presidents from the stigma of humiliating defeat was a dominant objective of the continuation of the war.

The documents showed “repetitive patterns of internal pessimism and desperate escalation and public deception in the face of what was, realistically, a hopeless stalemate,” as Ellsberg put it in his book.

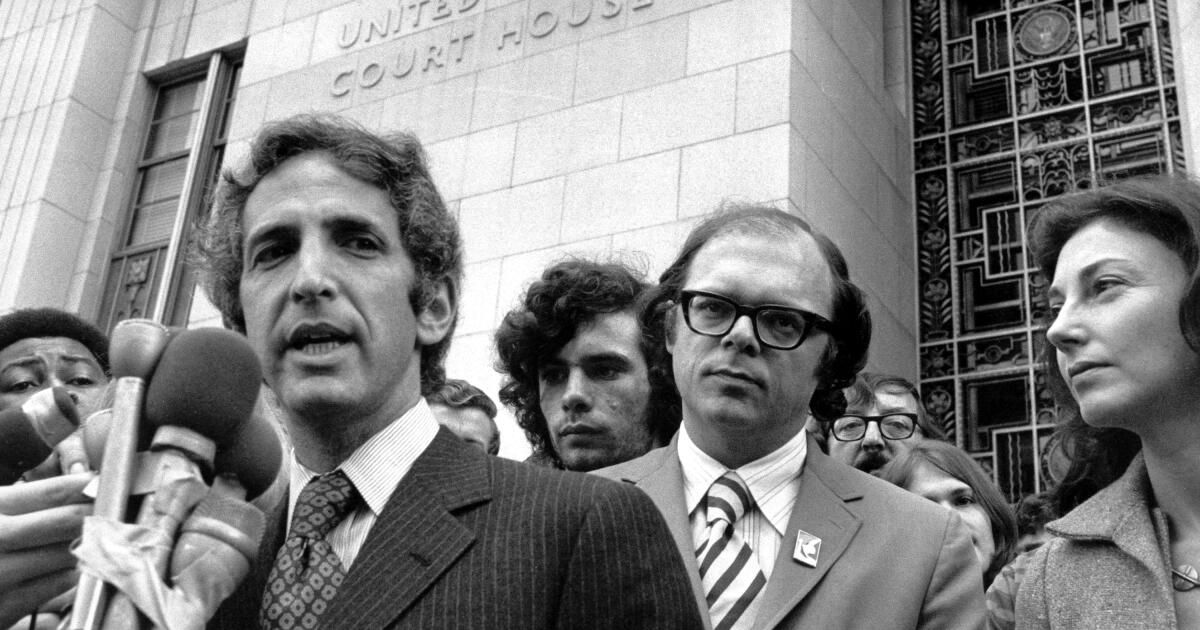

Anthony Russo enters a Los Angeles courtroom, where he admitted that he had “broken the rules” by duplicating top-secret documents. “It was my duty as an American citizen,” he said.

(Bettmann Archive)

A former Rand colleague, Anthony Russo, had encouraged Ellsberg to leak the documents to the media. Russo's girlfriend ran an advertising agency and offered him the use of her Xerox machine.

Ellsberg made copies after hours, sometimes bringing his 13-year-old son along to help. If the government locked him up, as seemed plausible, he would be unable to support his children. But he considered the stakes “bigger than me, or even my own family.”

Ellsberg turned the documents over to the New York Times, which began publishing them in June 1971. Other newspapers followed suit, much to the fury of the Nixon administration, and the U.S. Supreme Court decision upholding the media's right to publish became a First Amendment landmark. Steven Spielberg made a movie about it.

Less remembered was the criminal trial that followed in Los Angeles.

The panic that gripped the Nixon White House — and its hatred of Ellsberg — was captured on tapes from the Oval Office. The president’s advisers described Ellsberg as a traitor responsible for “an attack on the entire integrity of government” and “a devastating breach of security of the highest magnitude.”

Enraged at seeing Ellsberg portrayed as a national hero, Nixon vowed to destroy him, declaring, “We've got to get this son of a bitch.”

The Justice Department charged Ellsberg under the Espionage Act and he faced a possible sentence of 115 years in prison if convicted of conspiracy, espionage and theft of government property.

When he and co-defendant Russo went on trial in downtown Los Angeles in 1972, the questions were important: Had the revelations endangered national security? Were there circumstances in which the government's zeal for secrecy could be overridden in the public interest?

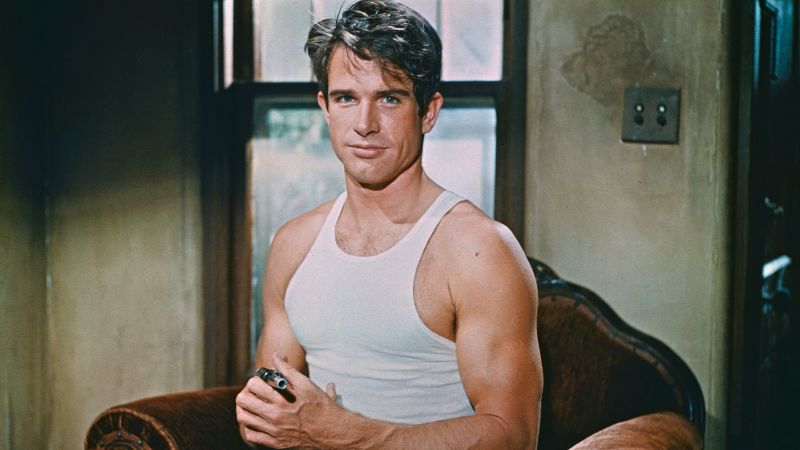

Daniel Ellsberg, a former Defense Department investigator who leaked the Pentagon Papers to the press, testifies before an unofficial House panel investigating the documents' significance in 1971.

(Associated Press)

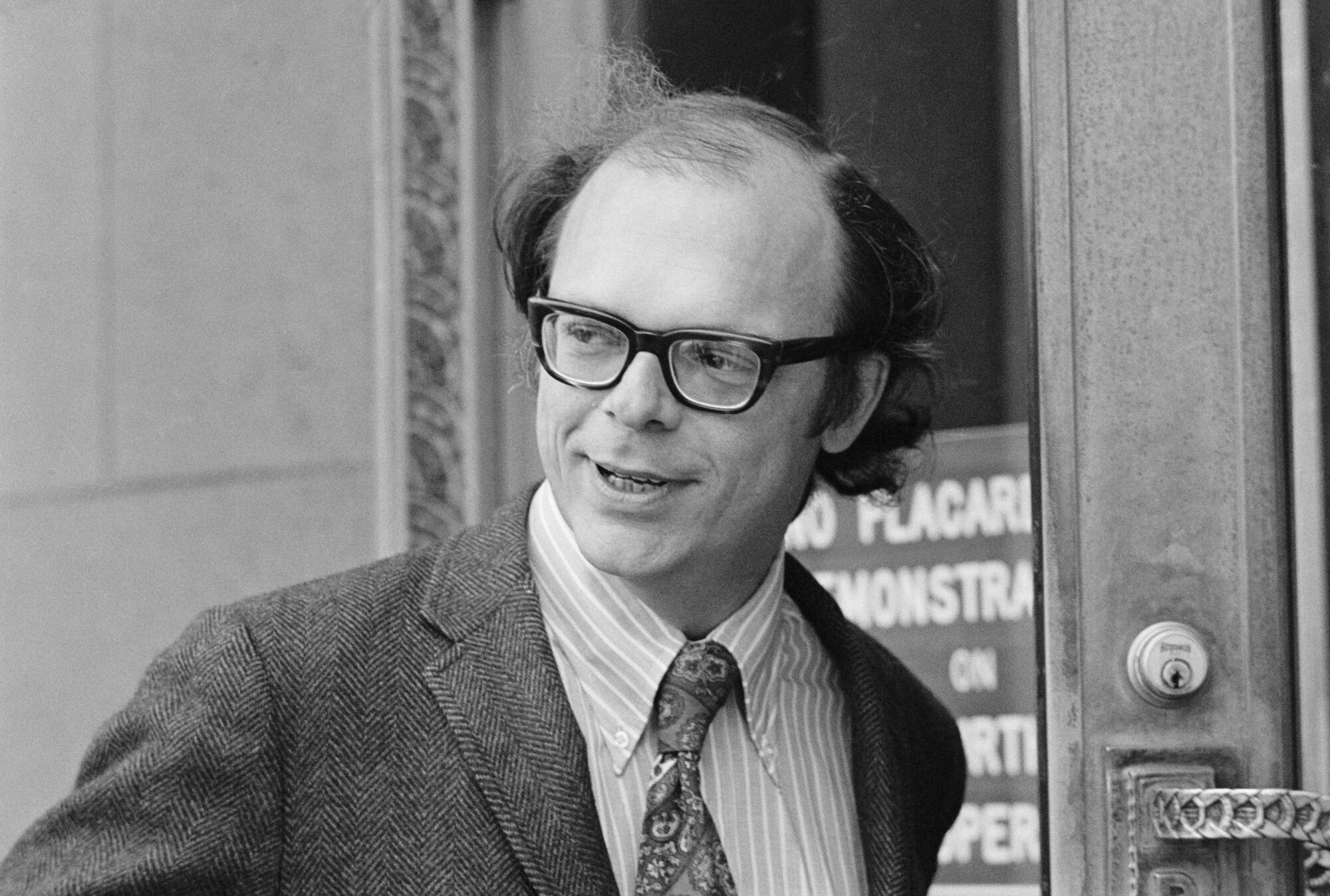

Mark Rosenbaum was a student at Harvard Law School when he took a leave of absence to assist the defense team.

“As far as I understand, this is the first trial in the history of the country that really examined the way the government lied to its people,” Rosenbaum, a longtime public interest lawyer in Los Angeles, recently told the Times. “Most people took what the government said as truth. This trial laid that bare. In 2024, it’s hard to remember how sweeping and revealing it was.”

What was on trial was not just U.S. foreign policy, but “the entire system of document classification,” Rosenbaum said. “We showed that what was classified as secret or top secret was actually an attempt to [suppress] politically embarrassing material.”

The defense team believed that Nixon’s Justice Department wanted the trial to be held on the West Coast in hopes of finding sympathetic jurors from the aerospace industry, which was heavily dependent on the Defense Department. Rosenbaum recalled that the jury consisted of “a lot of retired government employees” who seemed intent on securing a conviction.

“You could feel the bad vibes,” he said.

But appeal arguments prompted a months-long delay and a new jury was chosen that seemed friendlier to Ellsberg's side.

There was little disagreement about the facts. No one disputed that Ellsberg had taken the documents and photocopied them. But the defense argued that disclosure did not endanger national defense, that the documents related to previous presidential administrations, and that much of the material had been in the public domain anyway, albeit in scattered form. And before releasing the documents to reporters, Ellsberg had unsuccessfully tried to make them public by giving them to members of Congress.

Daniel Ellsberg, the lead defendant in the Pentagon Papers case, addresses a crowd in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1972, after an anti-war parade that ended at the state Capitol.

(Rusty Kennedy/Associated Press)

But Congress was “in the grip of absolute executive control,” defense attorney Charles Nesson told the judge, adding: “There was no choice but the one the defendants chose.”

In a recent interview with The Times, Nesson, now 85, said another defense argument was that Ellsberg had not actually stolen government property. He had photocopied documents and returned the originals. What he had done was release information, but “the government does not own the information.”

In late April 1973, well into the trial, District Judge Matt Byrne handed Ellsberg’s lawyers alarming reports he had received from the Justice Department. The White House-directed team of agents known as “the plumbers” had broken into the Beverly Hills office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in search of incriminating material.

Late one night, Rosenbaum said, he and another young lawyer drove to the small East Los Angeles home of a woman who had cleaned the psychiatrist's office and had seen the burglars. The lawyers had an issue of Time magazine with a picture of G. Gordon Liddy, the Watergate conspirator. The cleaning woman identified him as one of the burglars, Rosenbaum said.

“That started to open things up,” Rosenbaum said.

In another damning revelation for the government, the FBI admitted that it had captured Ellsberg's voice on wiretap recordings years earlier, and that the transcripts had disappeared.

But what ultimately derailed the case were the Nixon administration's unseemly overtures to the judge. The defense team learned that Judge Byrne had visited the president's home in San Clemente midway through the trial and that Nixon had offered him the job of running the FBI.

Nesson said it amounted to Nixon “trying to bribe the judge to somehow get a conviction.” It was “sort of a capstone to the misconduct that Ellsberg was revealing.”

The judge acknowledged the San Clemente meeting but said he turned down the FBI job. Shortly afterward, Nesson said, he received a call saying the judge had been seen in a park with Nixon aide John Ehrlichman.

“I knew he was a killer,” Nesson said. “The judge was finally cornered.”

Defense attorneys debated whether to disclose the information to the judge in court or inform him privately. Nesson opted to call him into his office.

“I have never really regretted the professional courtesy of warning him that he was about to be killed, indeed,” Nesson said.

In May 1973, Byrne declared a mistrial and dismissed all charges against Ellsberg and Russo based on government misconduct, saying, “Strange events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case.”

Daniel Ellsberg smiles with his wife Pat as they leave the Federal Building in Los Angeles on May 11, 1973, shortly after the judge in the Pentagon Papers case dismissed all espionage, theft and conspiracy charges against Ellsberg and his co-defendant, Anthony Russo.

(Associated Press)

Jurors filed into the office the defense attorneys had set up in downtown Los Angeles. It was clear that many had been in favor of acquittal.

The leaked documents and the resulting trial fueled a distrust and cynicism toward the government that only intensified as the Watergate scandal unfolded.

Did Ellsberg's leak help end the war? As Ellsberg argues in his book, the fight against the Watergate scandal prevented Nixon from blocking a congressional resolution to stop the bombings. And Nixon's attempt to cover up criminal activities by White House operatives (such as the burglary of Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office) would greatly influence his fall from grace and resignation.

With stricter laws on disclosing government secrets, Rosenbaum said Ellsberg's defense would have little chance in court today.

“Today, it would be an open-door affair” in favor of the government, Rosenbaum said, since now “the only burden on the government is to prove that the document is classified, and that’s it. 'Was the document classified?' 'Yes.' Done.”