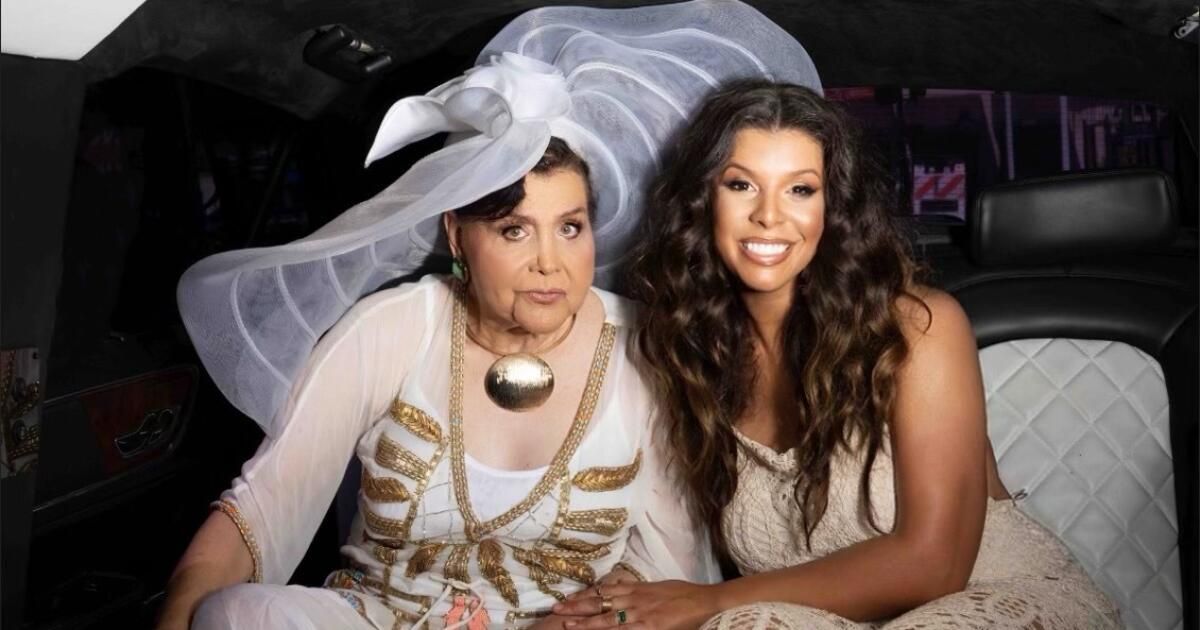

Sir Lady Java, a pioneering transgender artist and activist who boldly defied discriminatory laws and police harassment as a star of the Los Angeles nightclub scene in the 1960s, died Saturday after a stroke, it was confirmed Tuesday. close friends. She was 82 years old.

“It's a big loss for the community,” said actress Hailie Sahar, who is preparing to play Java in a biopic and was one of his primary caregivers for the past two years. “She started an LGBTQ+ movement before there was really an LGBTQ+ community to support her.”

Lady Java, as she was also known, worked as a drag queen, singer, dancer, comedian and “female impersonator” at a time when cross-dressing was prohibited without permission, conquering crowds in predominantly heterosexual clubs and running in circles with Luminaries of Los Angeles as Lena Horne.

Java was a designer and maker of hats, skills she incorporated into her own outfits. She began waiting tables at the Redd Foxx Club on La Cienega Boulevard in West Hollywood, but stood out for her beauty and was invited to the stage, where she had natural talent. He soon began performing regularly and alongside big names like Richard Pryor, friends said.

“Her comedic timing was on point,” said Sahar, also a transgender woman of color known for her portrayal of Lulu Abundance on the award-winning FX series “Pose.”

In 1967, Java joined the American Civil Liberties Union in a lawsuit challenging his arrest by the Los Angeles police for performing in drag without a permit, a violation of what was then known as Rule No. 9. , a local cross-dressing ordinance. He ultimately lost his case before the California Supreme Court, but the ordinance was struck down two years later.

Java's stance predates the uprising over similar anti-LGBTQ+ police harassment at New York's Stonewall Inn by two years, and has never received the same attention. However, it has gained greater attention in recent years as historians and younger queer people have sought to draw more attention to previously overlooked heroes of the queer rights movement, especially transgender people of color like java.

“The important thing about Java,” Sahar said, “is that Java came long before dance halls were created, long before the Stonewall riots in New York, so she was really a pioneer.”

Sahar said he first heard the name Java about 15 years ago, when a man at a rehearsal told him it reminded him of Java. Sahar said she returned home and started Googling Java and “fell extremely in love with its beauty and what it represented.”

He set out to find and learn about Java and finally succeeded. Soon, Java became her “trans mother” and a queer role model, a fellow “light-skinned mixed-race woman” who rose from humble roots to conquer Hollywood—bigotry and discriminatory laws be damned.

She also became a dear friend, Sahar said. “She was the funniest person you would ever meet. She was so witty, so intellectual, so elegant, but don't try her because she will let you know exactly how she feels,” Sahar said, laughing.

Jayce Baron, another of Java's caregivers in her later years, said queer people today “benefit as a community on the backs and shoulders of trans people of color, and they almost never give them credit or what they deserve.” “It belongs to them.”

That should change, he said, because understanding that history will be crucial to continuing the fight for queer rights in the future.

“If Java could do the work it did in the 1960s, we can continue that work today,” he said. “His legacy is not over.”

In fact, Java's legacy is particularly relevant today, queer activists said, as LGBTQ+ rights come under attack, reinforced by President-elect Donald Trump's victory in a campaign focused in part on an anti-transgender agenda.

Trevor Ladner, director of educational programs at One Institute, an LGBTQ+ history and education organization in Los Angeles, said he teaches Javanese history as part of the institute's youth program and learned of her death while researching her history with students during the weekend.

He said California law requires that school-age students be educated about the contributions of queer people and people of color, and Java's “pioneering fight for its labor rights” in the 1960s fits that bill perfectly.

“The importance of their story is underscored by continued legislative attacks on trans autonomy and drag entertainment,” Ladner said, “and the increasing visibility of trans youth in schools.”

Sahar said Java was “baffled” by the rise in anti-transgender sentiment in recent years because she “came from a time when they helped lay the groundwork” to turn the tide toward acceptance and never thought the country would give reverse.

But he also feels good about the biopic of his life, for which Sahar is seeking support with producer Anthony Hemingway.

“She felt that people who saw her life story and understood what it took to get here would have a better understanding of love, acceptance and equality,” Sahar said. It was something they both agreed on.

“Java told me, 'Honey, I did my job in the past. I fought for our rights. You have to decide what you are going to do,'” Sahar said. “And I said, 'Java, that's why we're making your movie.'”

In his own interview about the biopic before his death, Java said he felt it was “necessary to tell” his story, especially today.

“A lot of my brothers and sisters were killed in my time,” he said, “so I don't care who doesn't like it. “I'm going to tell it.”

Times staff writer Grace Toohey contributed to this report.