When Fernando Mendoza won the Heisman Trophy this weekend with another Latino finalist watching in the crowd, the Cuban-American quarterback did more than become the first Indiana Hoosier to win college football's top award, and just the third Latino to do so. He also subtly made a radical statement: Latinos not only belong in this country, they are essential.

At a time when questions swirl around the largest minority group in this country and cast us in a degrading, symbolic light: How could so many of us vote for Trump in 2024? Why don't we assimilate faster? Why does Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh think it's okay for immigration agents to racially profile us? – the fact that two of the best college football players in the country this year were Latino quarterbacks did not attract the headlines they would have garnered a generation ago. This is because we now live in an era where Latinos are part of the sports fabric in the United States like never before.

That's the untold thesis of four great books I read this year. Each one is anchored in Latin pride, but treats its subjects not only as curious and pioneers of the sport, but as great athletes who were and are fundamental not only to their professions and their community, but to society in general.

Shea Serrano writing about anything is like a really big burrito: you know it's going to be great and it exceeds your expectations when you finally bite into it, you swear you're not going to stuff it in one sitting, but you don't regret a thing when you inevitably do. He could write about concrete and this would be true, but fortunately his latest New York Times bestseller (four in total, probably making him the only Mexican-American author with that distinction) is about his favorite sport.

“Expensive Basketball” finds Serrano at his best, a mix of humility, rambling and hilarity (of Rasheed Wallace, the lifelong San Antonio Spurs fan wrote that the star forward “would collect technical fouls with the same enthusiasm and determination with the same enthusiasm and determination with which little children collect Pokémon cards”). The proud Texan's mix of styles (direct essays, lists, repeated phrases or words trotted out like incantations, copious footnotes) ensures that he always keeps the reader guessing.

But his genius lies in noticing things that no one else can notice. Who else would have crowned journeyman power forward Gordon Hayward as the scapegoat in Kobe Bryant's final game, the one in which he scored 60 points and led the Lakers to a thrilling fourth-quarter comeback? Did you link a Carlos Williams poem that a friend mistakenly sent to WNBA Hall of Famer Sue Bird? He reminded us that the hapless Charlotte Hornets, who haven't made the playoffs in nearly a decade, were once considered so great that two of their stars appeared in the original “Space Jam.” “Essential Basketball” is so good that you'll swear you'll just read a couple of Serrano's essays and not regret the afternoon that will go by as quickly as a Nikola Jokic assist.

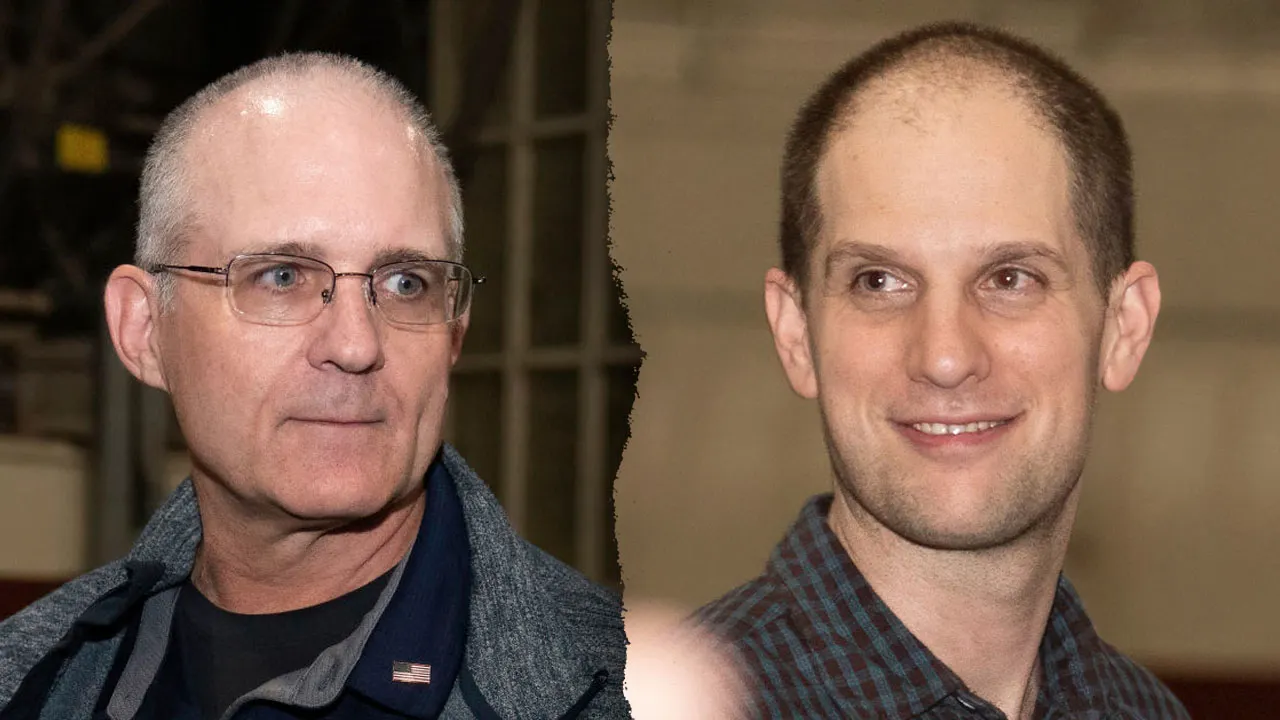

“Mexican-American baseball in the South Bay”

(Gustavo Arellano/Los Angeles Times)

I recommended “Mexican-American Baseball in the South Bay” on my regular blog. column three years ago, so why am I publishing its second edition? For one thing, the audacity of its existence: How can anyone justify turning a 450-page book about a little-known section of Southern California into an 800-page one? But in a time when telling your story because no one else will or will do a terrible job is more important than ever, the contributors to this tome demonstrate just how true that is.

“Mexican-American Baseball in the South Bay” is part of a long-running series on the history of Mexican-American baseball in the Latino communities of Southern California. The brilliance of this one is that it boldly asserts the history and stories of a community that is too often overlooked in Southern California Latino literature in favor of the eastern and Santa Ana sides of the region.

As series editor Richard A. Santillán noted, the reaction to South Bay's original book was so overwhelmingly positive that he and other members of the Latino History Baseball Project decided to expand it. Well-written essays introduce each chapter; Long captions for family and team photos function as yearbook entries. Especially valuable are the newspaper clippings from La Opinión that showed the vitality of the inhabitants of Southern California who never made it to the pages of the English-language press.

Perhaps only people with ties to the South Bay will read this book cover to cover, and that's understandable. But it's also a challenge for all other Latino communities: If people from Wilmington to Hermosa Beach to Compton can cover their sports history so thoroughly, why can't the rest of us?

(University of Colorado Press)

One of the most surprising books I read this year was “The Sanchez Family: Mexican-American High School and Collegiate Wrestlers in Cheyenne, Wyoming,” by Jorge Iber, a short read that addresses two topics rarely written about: Mexican-American freestyle wrestlers and Mexican-Americans in the Equality State. Despite its novelty, it is the most imperfect of my four recommendations. Since it is ostensibly an academic book, Iber loads the pages with quotes and references to other scholars to the point that it sometimes feels like a bibliography and one wonders why the author doesn't focus more on his own work. And in one chapter, Iber refers to his own work in the first person: teacherYou're great but you're not Rickey Henderson.

“The Sánchez Family” overcomes these limitations thanks to the strength of its protagonist, whose protagonists descend from ancestors born in Guanajuato who arrived in Wyoming a century ago and established a multigenerational wrestling dynasty worthy of the much more famous Guerrero clan. Iber documents how the success of several Sánchez men on the wrestling mat led to success in civic life and urges other scholars to examine how prep sports have long served as a springboard for Latinos to enter mainstream society, because nothing creates acceptance like winning.

“In our family we have educators, engineers and other professions,” Iber quotes Gil Sánchez Sr., a member of the first generation of fighters. “All because a 15-year-old boy [him]…he decided to become a fighter.”

Have you heard that boxing is a dying sport? The editors of “Rings of Dissent: Boxing and Performances of Rebellion” won't have it. Rudy Mondragón, Gaye Theresa Johnson and David J. Leonard not only refuse to accept that idea, but also describe these criticisms as “rooted in a racist and classist mythology.”

(University of Illinois Press)

They then go on to offer an electric and eclectic collection of essays on the sweet science that showcases the sport as a metaphor for the struggles and triumphs of those who have practiced it for more than 150 years in the United States. As expected, California Latinos get a leading role. Cal State Channel Islands professor José M. Alamillo investigates the case of two Mexican boxers who were denied entry to the United States during the 1930s due to the racism of the time, unearthing a letter to the Department of Labor that reads like a Stephen Miller rant: “California right now has a surplus of cheap boxers from Mexico, and something must be done to prevent the entry of others.”

Roberto José Andrade Franco retells the saga of Oscar De La Hoya versus Julio César Chávez, moving less towards the former's side and pointing out the assimilationist façade of the Golden Boy. Mondragón talks about the political activism of Central Valley light welterweight José Carlos Ramírez both inside and outside the ring. Despite the enthusiasm and love that each of the contributors to “Rings of Dissent” have in their essays, they do not romanticize it. No one is more clear about its beauty and sadness than Mondragón's fellow Latino students at Loyola Marymount. teacherPriscila Leiva. Examines the role of boxing gyms in Los Angeles, focusing on three: Broadway Boxing Gym and City of Angels Boxing in South Los Angeles, and the since-closed Barrio Boxing in El Sereno.

“Efforts to imagine a different future for oneself, for one's community, and for the city do not guarantee unequivocal success,” he writes. “Rather, like the sport of boxing, dissent requires fighting.”

If those aren't the wisest words for Latinos to adopt for the coming year, I'm not sure what are.