For decades, a graveyard of corroded barrels has littered the seafloor off the coast of Los Angeles. It was out of sight, out of mind: a not-so-secret secret that haunted the marine environment until a team of researchers found them with an advanced underwater camera.

Speculation abounded about what these mysterious barrels might contain. Surprising amounts of DDT near the barrels pointed to a little-known history of toxic contamination by what was once the nation's largest DDT manufacturer, but federal regulators recently determined that the manufacturer had not bothered with the barrels. (Instead, their acidic waste was dumped directly into the ocean.)

Now, as part of an unprecedented analysis of the legacy of ocean dumping in Southern California, scientists have concluded that the barrels may actually contain low-level radioactive waste. Records show that from the 1940s to the 1960s, it was not uncommon for hospitals, laboratories, and other local industrial operations to dispose of barrels of tritium, carbon-14, and other similar waste into the sea.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

“This is a classic bad versus worse situation. It's bad that we have potentially low-level radioactive waste at the bottom of the sea. “It's worse that we have DDT compounds spread over a wide area of the seafloor in worrying concentrations,” said David Valentine, whose research team at the University of California, Santa Barbara, first discovered the barrels and raised concerns about what might be there. inside. “The question we face now is how bad and how much worse.”

This latest revelation from Valentine's team was published Wednesday in Environmental Science & Technology as part of a larger, long-awaited study that lays the groundwork for understanding how much DDT is spread across the seafloor and how pollution could still be moving at 3,000. feet under water.

David Valentine, whose team at the University of California, Santa Barbara has been investigating the legacy of DDT dumping in the deep ocean, is preparing to collect more sediment samples from the seafloor.

(Austin Straub / For The Times)

Public concern has intensified since The Times reported in 2020 that dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, banned in 1972 following Rachel Carson's “Silent Spring,” continues to insidiously plague the marine environment. Scientists continue to trace significant amounts of this decades-old “forever chemical” throughout the marine food chain, and a recent study linked the presence of this once-popular pesticide to an aggressive cancer in California sea lions. .

Dozens of ecotoxicologists and marine scientists are now trying to fill key data gaps, and the findings so far have been one plot twist after another. A research team led by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego recently set sail to help map and identify as many barrels as possible on the seafloor, only to discover a multitude of discarded military explosives from the era of the Second World War.

And in the process of unearthing old records, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency discovered that from the 1930s to the early 1970s, 13 other areas off the coast of Southern California had also been approved for dumping. military explosives, radioactive waste and various refinery byproducts. including 3 million metric tons of oil waste.

In the study Published this week, Valentine found high concentrations of DDT spread over a wide swath of seafloor larger than the city of San Francisco. His team has been collecting hundreds of sediment samples as part of a large-scale, methodical effort to map the footprint of the spill. and analyze how the chemical might be moving through the water and whether it has broken down. After many trips to the sea, They have yet to find the limit of the landfill, but they concluded that much of the DDT in the deep ocean remains in its most potent form.

More detailed analysis, using carbon dating methods, determined that DDT dumping peaked in the 1950s, when Montrose Chemical Corp. of California was still operating near Torrance during the pesticide's postwar heyday, and before the emergence of formal regulations on ocean dumping.

Clues pointing to radioactive waste emerged in the process of sorting out this DDT story.

Jacob Schmidt, lead author of the study and a doctoral candidate in Valentine's lab, combed through hundreds of pages of old records and located seven lines of evidence indicating that California Salvage, the same company tasked with dumping DDT waste off the coast of the Angels. Angeles, had also dumped low-level radioactive waste into the sea.

The company, now defunct, had received a permit in 1959 to unload radioactive waste in containers about 150 miles offshore, according to the U.S. Federal Register. Although archived notes from the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission say the permit was never activated, other records show that California Salvage advertised its radioactive waste disposal services and received waste in the 1960s from a radioisotope facility in Burbank, as well as barrels of tritium and carbon-14. from a regional Veterans Administration hospital.

A research expedition led by the University of California, Santa Barbara found old discarded barrels 3,000 feet underwater near Santa Catalina Island.

(David Valentine/ROV Jason)

Given recent revelations that people tasked with disposing of DDT waste sometimes took shortcuts and simply dumped it closer to the port, researchers say they wouldn't be surprised if radioactive waste had also been dumped less than 150 miles away. the coast.

“There are quite a few paper trails,” Valentine said. “It's all circumstantial, but the circumstances seem to point towards this company taking whatever waste people gave them and transporting it out to sea… along with the other liquid waste we know they were dumping at the time.”

Ken Buesseler, a marine radiochemist who was not involved in the study, said that generally speaking, some of the most abundant radioactive isotopes dumped into the ocean at the time, such as tritium, would have largely decayed over the past 1980s. years. But many questions remain about what other potentially more dangerous isotopes might have been dumped.

The sad reality, he noted, is that it wasn't until the 1970s that people started taking radioactive waste to landfills instead of dumping it in the ocean.

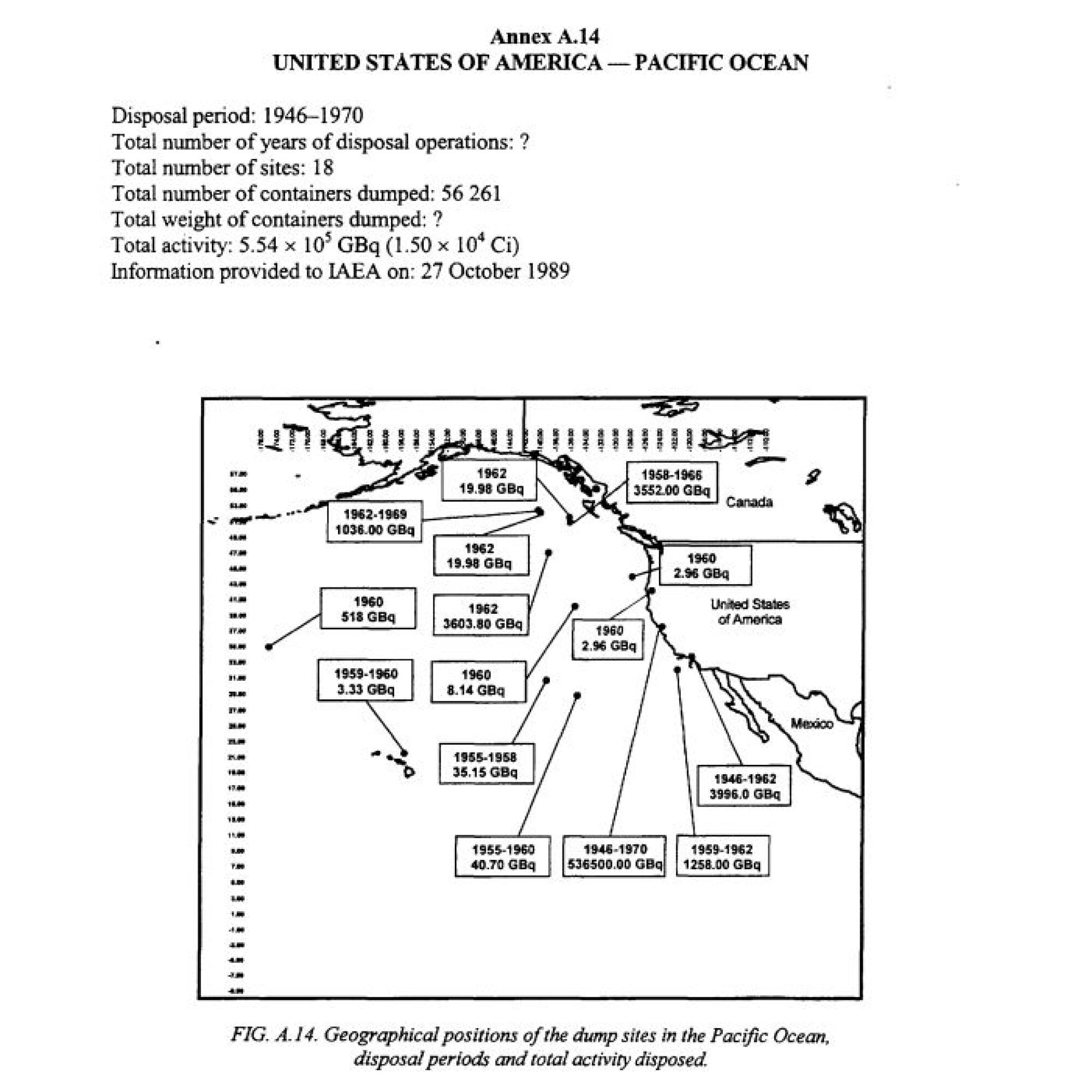

He pulled out an old map published by the International Atomic Energy Agency that showed that between 1946 and 1970, more than 56,000 barrels of radioactive waste had been dumped into the Pacific Ocean on the U.S. side. And around the world, even today, nuclear power plants and decommissioned plants, such as Fukushima, Japan, continue to release low-level radioactive waste into the ocean.

In a 1999 report by the International Atomic Energy Agency titled “Inventory of Radioactive Waste at Sea,” a grainy map shows that at least 56,261 containers of radioactive waste were dumped in the Pacific Ocean between 1946 and 1970.

(International Atomic Energy Agency)

“The problem with the oceans as a dumping solution is that once they're there, you can't go back and get them back,” said Buesseler, senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and director of the Center for Marine and Environmental Radioactivity. “These 56,000 barrels, for example, we will never recover.”

Mark Gold, an environmental scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council who has worked on DDT's toxic legacy for more than 30 years, said it's disturbing to think how big the consequences could be from the dumping in oceans across the country and the world. Scientists have discovered DDT, military explosives, and now radioactive waste off the coast of Los Angeles because they knew how to look. But what about all the other landfills where no one is looking?

“The more we search, the more we find, and each new piece of information seems to be more terrifying than the last,” said Gold, who called on federal officials to act more boldly on this information. “This has shown how egregious and damaging the dumping has been off our nation's coast, and that we have no idea how big the problem is and how big it is nationally.”

U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Calif.) and Rep. Salud Carbajal (D-Santa Barbara), in a letter signed this week by 22 members of Congress, urged the Biden administration to commit dedicated long-term funding to both studies. and solve the problem. (So far, Congress has appropriated more than $11 million in one-time funding that led to many of these initial scientific findings, and recently an additional $5.2 million in state funding initiated 18 more months of research.)

“While DDT was banned more than 50 years ago, we still have only a murky picture of its potential impacts on human health, national security and ocean ecosystems,” the lawmakers said. “We encourage the administration to think about the next 50 years, creating a long-term national plan within the EPA and [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] to address this toxic legacy off the coasts of our communities.”

As for the EPA, regulators urged the growing research effort to stay focused on the agency's most burning questions: Is this legacy pollution still moving through the ocean in a way that threatens the marine environment or human health? ? And if so, is there a potential path to remedy it?

EPA scientists have also been refining their own sampling plan, working with several government agencies, to understand the many other chemicals that had been dumped into the ocean. The hope, they said, is that all of these research efforts combined will ultimately inform how future investigations of other offshore landfills could be conducted, whether along the Southern California coast or in other parts of the country.

“It is extremely overwhelming. … There's still a lot we don't know,” said John Chesnutt, a Superfund section manager who has been leading EPA's technical team in investigating ocean spills. “Whether it's radioactivity or explosives, there are potentially a wide range of contaminants that are not good for the environment and the food web, if they actually move through it.”

Newsletter

Towards a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and be part of the conversation and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.