On Tuesday night, Ria Abernathy was driving home from her son's house in Oroville when an ominous scene unfolded before her. A huge plume of neon orange smoke rose on the horizon.

The 55-year-old appliance service manager stopped to take a photo of the Thompson Fire, which would burn more than 3,500 acres of dry grass and brush near the Northern California town the following night and prompt an evacuation order for thousands of residents.

It didn’t seem likely that the flames would reach Abernathy’s home, about 25 minutes away in the Butte County community of Magalia. But the image was eerily similar to what he saw one morning in November 2018, just before he fled his Paradise home amid the Camp Fire. That blaze would kill 85 people and destroy everything Abernathy owned.

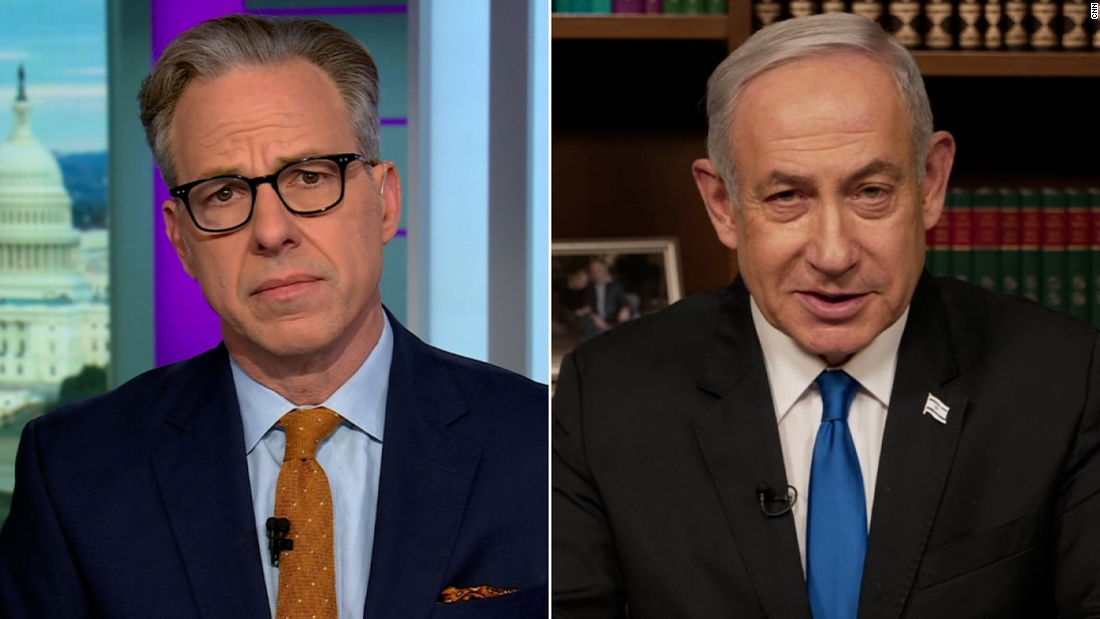

The Thompson Fire creates an eerie scene as it burns near Oroville, California, on Tuesday.

(Ria Abernathy)

“It brings back a lot of bad memories, even a bit of PTSD, no doubt,” he said of the most recent fire.

In recent years, Butte County has been rocked by one disaster after another: the Oroville Dam spillway failure that prompted the evacuation of 180,000 people in 2017; the massive North Complex fire, which killed 16 people in 2020; the even more massive Dixie fire, which burned much of the county in 2021, becoming the first to burn from one side of the Sierra Nevada to the other. But perhaps no event is more deeply embedded in the region’s psyche than the Camp fire, which remains California’s deadliest wildfire to date and left wounds that have been slow to heal.

“I think it’s really important for people to know that with the fire — the original fire — people are still fighting,” Abernathy said. “I lost all my history. A lot of people lost their history, and they’re not going to get it back.”

Abernathy moved to Butte County from Southern California when her oldest son, now 39, was 5. She wanted a better life for her children and was drawn to the mountain views, abundant wildlife and friendly people.

She knew wildfires were a risk, given the recurring droughts, dense forests and winding canyons. A week or two before the Camp Fire, she had been warned that she might have to evacuate because of another fire, so she packed her car and was ready to go. About four days before the Camp Fire, she had unloaded everything, thinking she was safe. By the time the flames approached her door, she was out of time.

“I dropped everything and said, ‘Okay, we’ll be back,’” he said. “We never went back.”

Abernathy, an uninsured renter, first moved to Corning but says she lost her home because of a miscommunication with the Federal Emergency Management Agency. She ended up living in a trailer in a church parking lot for eight months.

He eventually received an $80,000 settlement from Pacific Gas & Electric Co., whose equipment sparked the Camp Fire and which pleaded guilty to 84 counts of involuntary manslaughter in connection with the blaze. But after paying taxes on the settlement and giving a third to his attorney, he didn’t have much left. Even less considering that his PG&E utility bill skyrocketed from $150 a month to $500 a month after the fire, he said.

“I'm pretty much shut out because I can't afford to live here,” she said, adding that her landlord has struggled to maintain homeowner's insurance on the property as insurers raise rates or leave the state altogether.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do because I’m taking care of my mother, who is 84, and my grandson, who is 19. I don’t want to move away from here (this is where all my children grew up), but I can’t afford to be here anymore.”

Abernathy’s son and his wife recently bought a home in Oroville, closer to the Thompson Fire. She is hopeful that they will have an easier time fleeing the Camp Fire than she did, if it comes to that. The town has multiple access points, unlike Paradise, which had few roads out of town.

By Wednesday evening, the couple had not yet been ordered to evacuate, but Abernathy had already told them to pack their bags and put them in the car, just in case.