More than 250 black sailors, punished for refusing to return to dangerous jobs after a powerful munitions explosion in Chicago Harbor killed 320 sailors in 1944, were fully exonerated by the Navy on Wednesday.

The exoneration came on the 80th anniversary of the tragic explosion during World War II, and followed decades of petitions and requests from family members, advocates and historians who argued that the 258 sailors who refused to return to work were subjected to racism and were unfairly persecuted and court-martialed in the segregated Navy.

The explosion was the “deadliest disaster on the U.S. home front during World War II.”

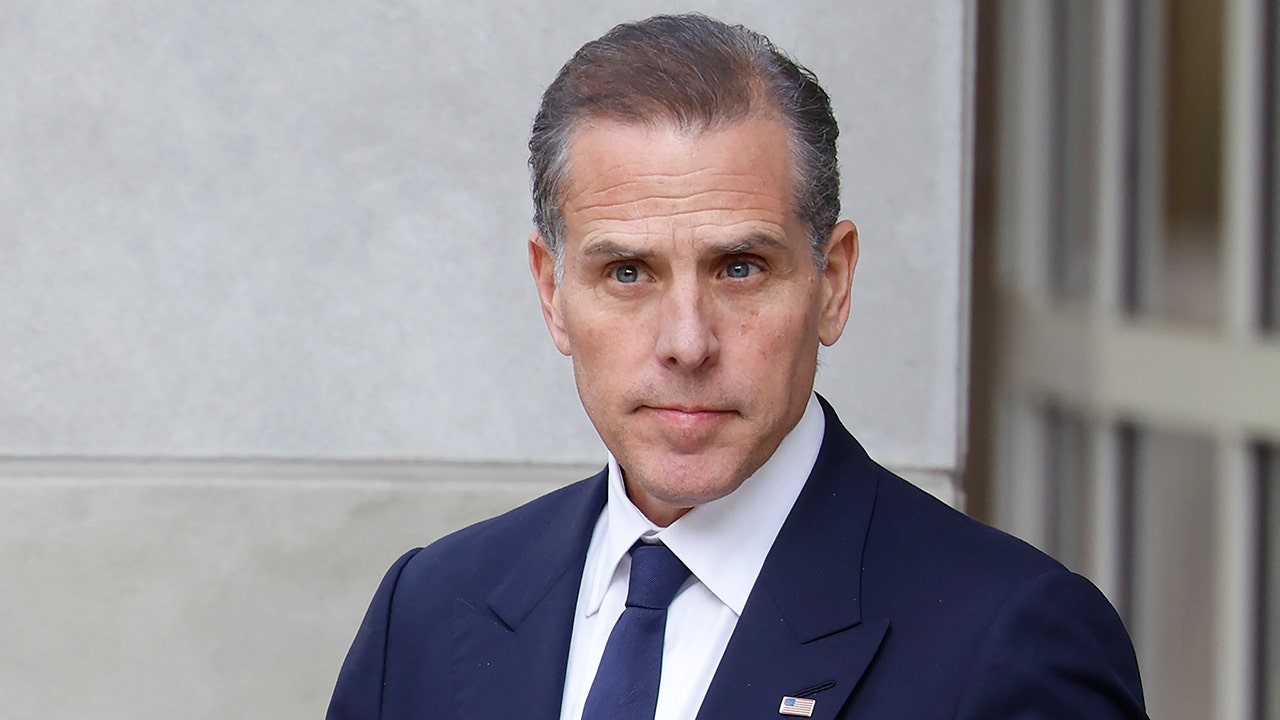

In a statement, President Biden said the decision “rights a historic wrong.”

“Today’s announcement marks the end of a long and arduous journey for these Black sailors and their families, who fought for a nation that denied them equal justice under the law,” Biden said in the statement.

While the white supervising officers were given hardship leave after the explosion, the surviving black sailors were ordered back to work loading ammunition onto ships and cleaning up the carnage left by the blast.

At the time, the U.S. military was segregated and most of the sailors who loaded and unloaded ships in Chicago harbor were black. Of the 320 dead, 202 were African-American, according to the National Park Service, which oversees the memorial at the site of the explosion.

In an interview with the Associated Press, Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro called it “a horrible situation for the black sailors who remained.”

Located on Suisun Bay, the Port Chicago naval barracks began planning just after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, according to naval historians.

Before the explosion, sailors had warned of poor conditions in the port.

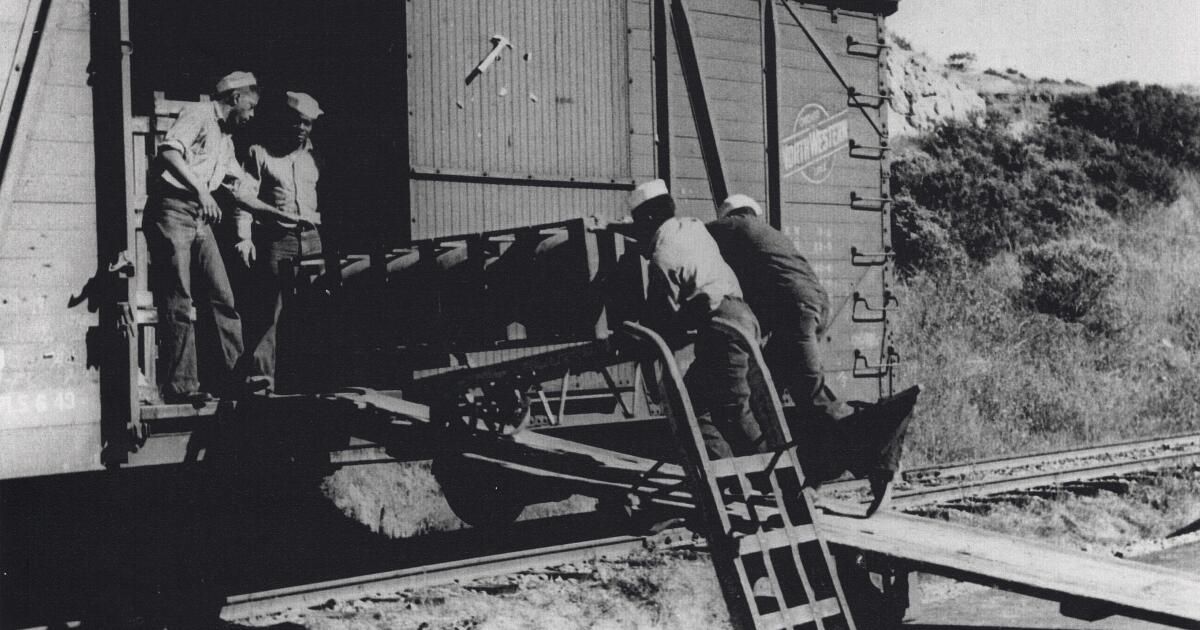

Naval historians noted that sailors assigned to the grueling job of loading ships with munitions for the war were poorly trained, faced dangerous working conditions, low morale, and mounting quotas that demanded around-the-clock work.

Then, shortly after 10 p.m. on July 17, 1944, there was a massive munitions explosion while the SS Quinault Victory and SS EA Bryan were docked at the wharf.

The cause of the explosion was never determined.

Less than a month later, black sailors were ordered back to work without proper training or protective equipment.

The 258 men who refused to return were confined for three days on a barge.

The sailors were tried and convicted in a military court, given bad conduct discharges and fined three months' pay. Fifty of the men were identified by the Navy as leaders and were charged with conspiring to commit mutiny. They were found guilty, sentenced to 15 years in prison and dishonorably discharged.

The treatment of black sailors at the time and in the decades following the deadly explosion highlighted the racist treatment of black members of the military.

Naval historians noted, for example, that one investigation into the explosion focused on the challenges faced by mostly black workers on the ground, and attributed the lack of training to racist tropes against black sailors.

“The report raised no questions about the leadership responsibilities of white officers,” according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

During the military trial, then-NAACP Chief Warrant Officer Thurgood Marshall held open-air press conferences, where he spoke out against discriminatory actions.

Marshall, before he became one of the best-known Supreme Court justices in history, wrote that “justice can be done in this case only by a complete reversal of the findings.”

The NAACP continued to call for the sailors' exoneration for decades, even sending a resolution to the Secretary of the Navy in 2023 calling for the sailors' exoneration.

On Wednesday, Del Toro told the Washington Post that the decision was made after a Navy investigation found legal errors committed in the 1944 courts-martial.

The ruling exonerating the sailors, he told the Post, “clears their names, restores their honor and recognizes the courage they displayed in the face of immense danger.”