In November 2017, days after her daughter Mallory Smith died from a drug-resistant infection at the age of 25, Diane Shader Smith typed a password into Mallory's laptop.

At this point, staying alive is a full-fledged mission, requiring all my energy and hours each day. I need to fight the deadly and resistant chronic bacteria that eat away at my fragile, scarred lungs. Fight the billions of bacteria invading my lungs and eliminate mucus so I don't feel like I'm breathing through a straw with a rock weighing down my chest.

– Mallory Smith, October 16, 2014

Her daughter gave it to her before undergoing double lung transplant surgery, with instructions to share any writing that might help others if she didn't survive.

I had this idea today that I wanted to write before it leaves my mind or I stop feeling inspired or I forget it or something inside me tells me it's not possible. I want to start an online media outlet (podcast? website?) that tells the stories of people who have struggled with something in their life and found hope somewhere.

— Mallory Smith, July 20, 2015

The transplant was successful, but Burkholderia cepacia —an antibiotic-resistant bacterial strain that first colonized his system when he was 12—took hold. After a lifetime with cystic fibrosis and 13 years fighting an invincible infection, Mallory's body couldn't take it anymore.

Cepacia has taken over and it's time to think about a transplant option. I realize that I want to write my story.

— Mallory Smith, July 29, 2016

In the midst of grief and pain, Shader Smith found herself reviewing 2,500 pages of a journal her daughter had kept since high school. It chronicled Mallory's hopes and triumphs as an athletic and enthusiastic student at Beverly Hills High School and Stanford University, and her private despair as bacteria devastated her systems and sapped her considerable strength.

In the years since, the magazine has become a source of comfort for Shader Smith as he traveled the world speaking about the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance. Now it's also the inspiration for two new projects that she hopes will generate greater understanding of the public health crisis that prematurely ended the life of her daughter and could cost millions more.

“Diary of a Dying Girl” draws from Mallory Smith's own writings, chronicling her 13-year battle with an antibiotic-resistant lung infection.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

On Tuesday, Random House published “Diary of a Dying Girl,” a selection of Mallory’s diary entries. On the same day the launch of the World Journal of Antimicrobial Resistancea website that compiles global stories of people fighting pathogens that our current pharmaceutical arsenal cannot defeat.

An estimated 35,000 people die each year in the United States from drug-resistant infections. according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Worldwide, antimicrobial resistance is estimated to directly kill 1.27 million people each year and contribute to the deaths of millions more.

Despite the growing number of victims – and the prospect of a eventual wave in superbug deaths: the development of new antibiotics has stalled.

Shader Smith is well aware of what we stand to lose when medicine can no longer save us.

“I don't want to live in a post-antibiotic world,” Shader Smith said. “Until people understand what's at stake, they won't care. My daughter died because of this. That's why I care deeply.”

Over the past 50 years, opportunistic pathogens have developed defenses faster than humans can develop drugs to combat them.

The misuse of antibiotics has played a major role in this imbalance. Insects that survive exposure to antibiotics pass on their resistant traits, leading to more resistant strains.

As crucial as they are, antibiotics do not have the same financial incentives for their developers as other drugs. They should not be taken long term, as should medications for chronic diseases such as diabetes or high blood pressure. The most potent ones should be used as little as possible to give bacteria less opportunity to develop resistance.

“The public does not understand [the] scope of the problem. “Antimicrobial resistance is truly one of the major public health threats of our time,” he said. Emily Wheeler, director of infectious disease policy at the Biotechnology Innovation Organization. “The antibiotic portfolio today is already inadequate to address the threats we know, without even considering the continued evolution of these insects as the years go by.”

Despite the global nature of the threat, Shader Smith said, the response from public health officials is curiously disjointed.

For one thing, no one can agree on a single name for the problem, he said. Different agencies address the issue with an “alphabet soup” of acronyms: the World Health Organization applications AMR as an abbreviation for antimicrobial resistance, while the CDC prefer ARKANSAS. Medical journals, doctors and the media alternately refer to multidrug resistance (MDR), drug-resistant infections (DRI) and superbugs.

“It doesn't matter what you call it. We just have to all call it the same thing,” said Shader Smith, who works as a publicist and marketing consultant.

Since Mallory's death, Shader Smith has made it her mission to get people and organizations working on antimicrobial resistance to talk to each other. For the Global AMR Diary, he enlisted the help of a dozen agencies working on the issue, including the CDC, the WHO, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (the equivalent of the CDC in the European Union) , the Biotechnology Innovation Organization and others.

Antimicrobial resistance may “seem abstract given the magnitude of the problem,” said John Alter, chief of external affairs at the Antimicrobial Resistance Action Fund, one of the organizations involved in the project. “Knowing that there are millions of families right now going through similar struggles to what Mallory experienced is simply unacceptable,” she said.

“This first-hand experience not only helps others who might be going through something similar, but also reminds those tasked with creating solutions and caring for who they are working for. “It’s not just test tubes or charts,” said Thomas Heymann, executive director of the Sepsis Alliance, another contributor.

The online diary stories are often heartbreaking. A 25-year-old pharmacist from Athens had to stop her cancer treatment when an extremely resistant strain of Klebsiella attacked. A veterinarian in Kenya suffered a permanent disability after contracting resistant bacteria following hip surgery. Around the world, routine outpatient procedures and illnesses have quickly become life-threatening as opportunistic viruses take hold.

Mallory was 12 years old when her doctor called her to confirm that her cultures were positive for an extremely resistant strain of cepacia, a form of bacteria found widely in soil and water. The pathogen can be deadly for people with underlying conditions such as cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder that impairs the ability of cells to effectively clear mucus from the lungs and other body systems.

The life expectancy of people with cystic fibrosis has increased since Mallory's diagnosis in 1995, and many of them live to be 40 years old or older. He cepacia He restricted that possibility for her.

“This is all we're going to have,” Mallory wrote in June 2011, at the end of her freshman year at Stanford, “so if you're not actively seeking happiness, then you're crazy. And I don't think I would have this perspective if I didn't have resistant bacteria that would probably kill me.”

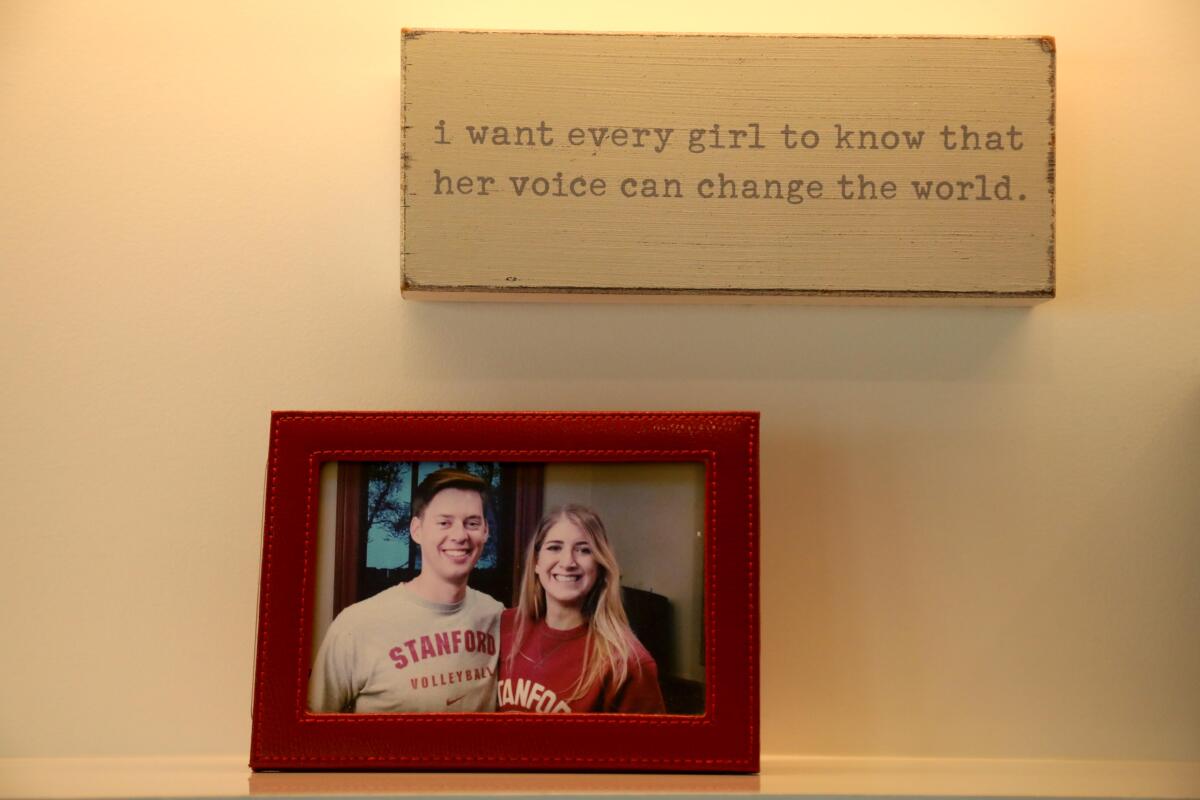

A shrine to Mallory Smith. He battled a drug-resistant bacteria from age 12 to 25, all through high school and then at Stanford. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Mallory's intuition that her journal could be valuable to others was prophetic. “People can easily understand and relate to real experiences,” said Michael Craig, director of the CDC's Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy and Coordination Unit. “The World AMR Journal takes this approach and expands it with a global perspective, increasing the potential to reach more people around the world with these critical messages.”

An earlier version of Mallory's diaries was published in 2019 as “Salt in My Soul: An Unfinished Life.” The new book includes entries that Shader Smith said she was not prepared to deal with immediately after Mallory's death: some that address depression and private despair, relationship concerns and body image issues complicated by chronic illness.

It also includes a coda on phage therapy, a promising advance against antimicrobial resistance.

As cepacia overwhelmed Mallory's system in the weeks after her transplant, her family got an experimental dose of phage therapy. Widely used to treat infections before the advent of antibiotics, phages are viruses that destroy specific bacteria. The treatment came too late to save Mallory's life, Shader Smith writes in a final chapter of the book, but her autopsy revealed that the phages had begun working as intended.

Systems that bring new medications to patients move slowly, Shader Smith said, and “Mallory could have been saved if they had moved faster.” Her mission now is to make sure that happens.

“Mallory died six years ago. “Six years is a long time, day after day,” she stated. “And I've never taken my foot off the pedal.”