Most Asian American adults support using the SAT and other standardized tests, along with high school grades, in college admissions decisions, but reject considering race or ethnicity in determining access, according to a new national survey released Wednesday.

Most also think it is unfair for colleges to consider an applicant's athletic ability, family ties, ability to pay full tuition or parents' educational levels when determining who should receive acceptance letters, the survey found.

At the same time, a majority of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders surveyed believe slavery, racism and segregation should be taught in schools and oppose individual school boards restricting classroom discussion about specific issues, as some conservative districts have done.

In general, AAPI adults value higher education not only as a path to economic well-being, but also to teach critical thinking, encourage the free exchange of ideas, and promote equity and inclusion.

The survey conducted by AAPI Data, a UC research firm, and the Associated Press-NORC Public Affairs Research Center interviewed a nationally representative sample of 1,068 AAPI adults ages 18 and older. The survey, conducted April 8-17 in English, Mandarin, Cantonese, Vietnamese and Korean, has a margin of error of 4.7 percentage points.

The survey offers a comprehensive look at attitudes toward education among Asian Americans, who make up a disproportionately large share of students at the University of California and other selective institutions but are often overlooked in political discussions. on equity and diversity.

Several polls have shown that Asian Americans support affirmative action, depending on how the question is asked. A 2022 poll found 69% support when respondents were asked if they favored programs to help blacks, women, and other minorities access higher education. But Asian American plaintiffs who led a landmark lawsuit against Harvard University argued that affirmative action policies that use race as a factor in admissions discriminated against them. Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down such race-conscious practices.

In the new survey, the question about using race in admissions, worded without context about who it would help, garnered little support. When asked if they thought it was “fair, unfair, or neither fair nor unfair for colleges and universities to make decisions about student admissions” based on race and ethnicity, 18% of respondents said it was fair, 53% said it was unfair and 27% said it was fair. % said it was neither.

The AAPI Data/Associated Press-NORC survey is among the first to assess Asian Americans' attitudes about standardized testing and other metrics for college admissions, along with broader questions about the value of education.

“The stereotype of AAPIs might suggest that they care about education only in a limited way, as it relates to economic mobility and hard skills related to job prospects,” said Karthick Ramakrishnan, professor of public policy and political science. from UC Riverside and founder of AAPI. Data. “This study reveals a more nuanced and complete portrait, illustrating that AAPI individuals value education…also to foster critical thinking and nurture a more informed citizenry.”

A large majority (71%) of respondents believe the history of slavery, racism, segregation, and the AAPI community should be taught in public schools. A smaller majority, 53%, favor teaching about sex and sexuality, including 72% of AAPI Democrats and 25% of Republicans.

In general, AAPI adults have similar views as the general American public about the keys to children's success: hard work, time spent with parents, and what schools they attend. However, Asian Americans are much more likely to believe that the neighborhoods they live in are important to educational success: 62%, compared to 49% of all Americans. Ramakrishnan said research has shown that AAPI families are more willing to move to areas with good schools even if it means living in worse housing.

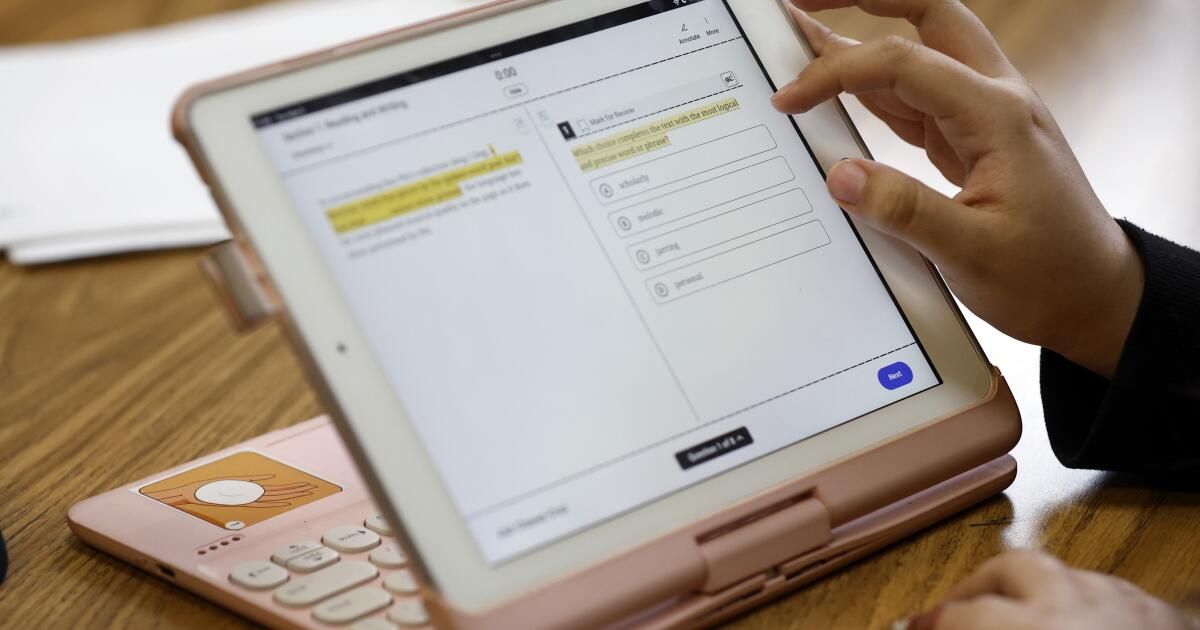

The Asian American support for standardized testing comes as several elite universities have reinstated those admission requirements after suspending them during the pandemic. In recent months, Harvard, Caltech, Yale, Dartmouth and the University of Texas at Austin, among others, have reinstated testing mandates.

Some institutions say their reviews showed that testing requirements increase diversity, benefiting applicants with less access to a rigorous high school curriculum, strong letters of recommendation or impressive extracurricular activities. Others have said it is more difficult to assess an applicant's readiness for college work without standardized testing, especially since many educators have reported significant grade inflation since the pandemic.

The University of California and California State University have eliminated standardized testing requirements for admission.

While some UC leaders have indicated interest in reviewing the impact of that decision on student outcomes, faculty leaders say there may not be much interest in it. The UC Board of Regents rejected the Academic Senate's recommendation to maintain testing requirements and voted to ban them from admissions decisions.

USC continues its test-optional policy (accepting scores from those who wish to submit them but not penalizing those who do not) and is reviewing whether to continue that course.

Frank Xu, a San Diego father of a high school sophomore and MIT student, said he opposed the UC regents' decision to reject testing mandates and believes the preponderance of research shows that Test scores are highly correlated with college success.

“I'm all for research-based decisions, and I felt like at UC it was a completely political decision to ignore the faculty senate,” he said.

But some Asian American students say the tests are an unfair factor in admissions decisions.

At Downtown Magnets High School, students Rida Hossain and Shariqa Sultana said their families couldn't afford to prepare for the exams, with annual incomes of less than $30,000 and relatives in Bangladesh to support.

“Standardized tests do not reflect a student's ability on how they will perform in higher education, because in the classroom, they will be writing a lot of essays, research, collaboration, and projects that wouldn't necessarily be included on a multiple-choice exam,” Shariqa said. “Your actual performance in class and in your extracurricular activities is a better metric than a test that determines your entire future.”

Ramakrishnan said there are several reasons why many Asian Americans support standardized testing. Most are immigrants from China, Korea, India and other countries that use these types of tests for college admissions, he said. They are accustomed to a high-stakes testing system and see it as an equitable way to determine college access, compared to wealth or political connections.

The poll supports that point, showing that 70% of AAPI respondents who are immigrants support testing, compared to 56% of those born in the United States. A plurality of respondents, 45%, said it was fair to consider personal experiences with hardship or adversity.

But 69% of respondents said legacy admissions (preferential treatment for children of alumni) were unfair, while 48% opposed considering an applicant's ability to pay. A majority, 54%, do not believe it is fair to consider whether applicants are the first in their family to attend college.