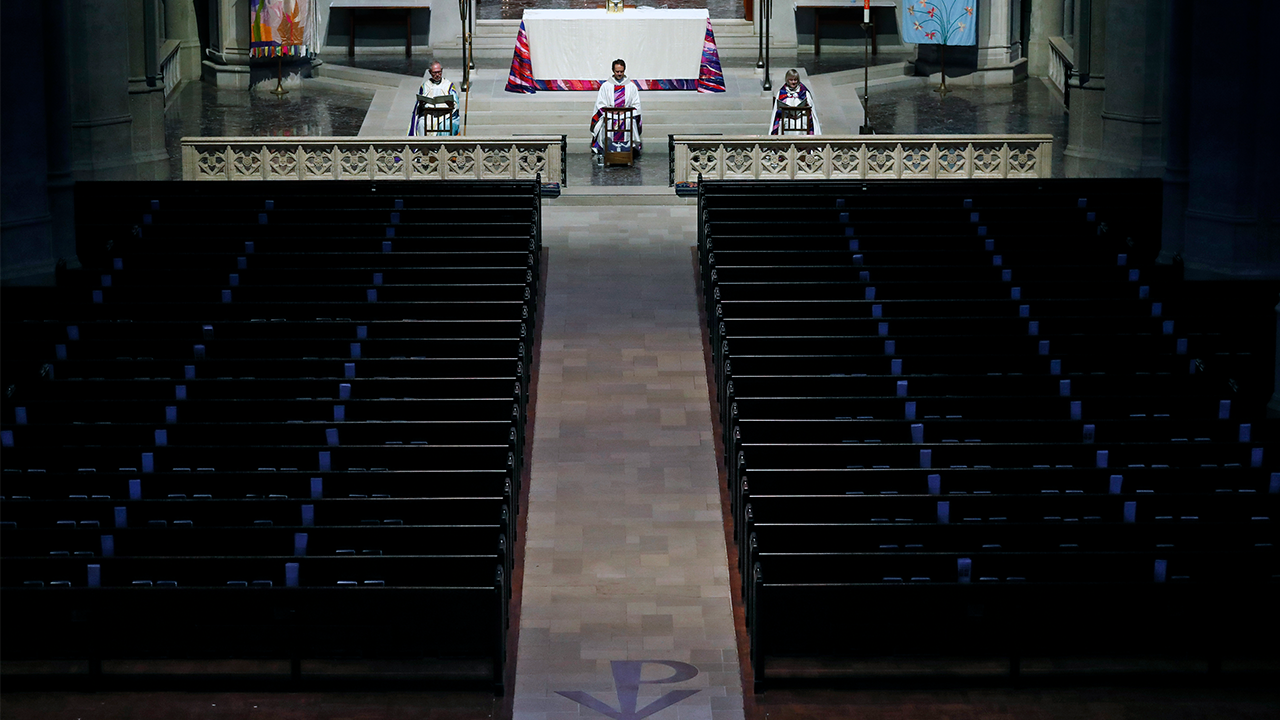

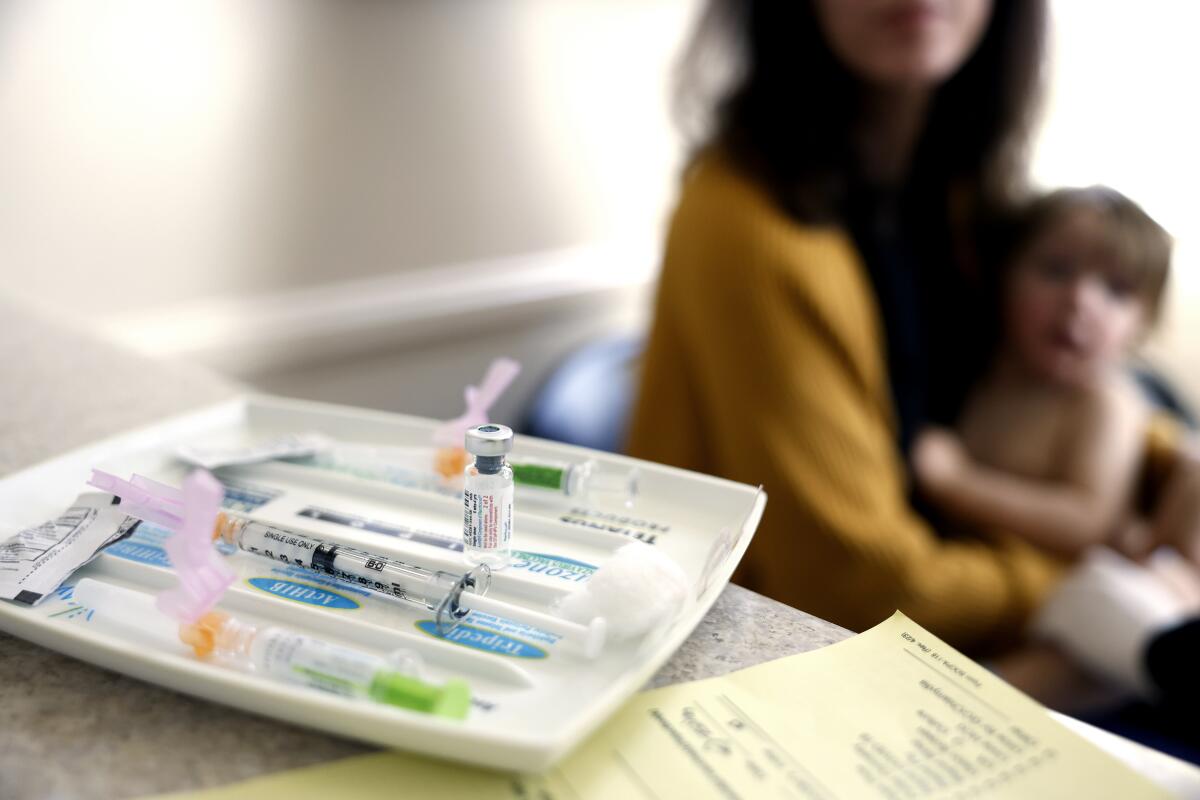

As measles cases emerge across the country this winter (including several in California), one group of children is raising deep concerns among pediatricians: infants and toddlers of vaccine-hesitant parents who are delaying getting measles shots. measles, mumps and rubella in their children.

Pediatricians across the state say they have recently seen a sharp increase in the number of parents concerned about routine childhood vaccines requiring their own vaccination schedules for their babies, creating a worrying group of very young children who may be at risk. of contracting measles. , a potentially fatal but preventable disease.

“Especially in the beginning, when a parent is already feeling very vulnerable and doesn't want to give their beautiful new baby something if they don't need it, it makes them think, 'Maybe I'll just delay it.' and he will wait and see.'” said Dr. Whitney Casares, a pediatrician and author who has written about vaccinations for the American Academy of Pediatrics. “What they don't realize is that if they don't vaccinate according to the recommended schedule, that can expose their children to many risks.”

It is difficult to know how widespread these delays have become. California carefully tracks the rate of kindergartners who have been vaccinated against measles, but does not have complete data for children at younger ages.

Dr. Eric Ball has seen the change firsthand. Ball said that at his Orange County pediatric practice he has noticed an increase in parents asking about delays since the COVID-19 pandemic, as politicization and misinformation about that vaccine has seeped into discussions. about routine childhood vaccines, including those for measles, mumps and rubella. , known as MMR.

Dr. Eric Ball examines 9-month-old Noah at Southern Orange County Pediatric Associates in Ladera Ranch on February 28.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

However, instead of an outright rejection, these vaccine-hesitant parents express a softer kind of reluctance, asking if it is possible to use an “alternative schedule” of vaccines, rather than sticking to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations. Disease Control and Prevention. Sometimes they seek to delay vaccinations by a few months, and sometimes by several years.

“I have patients who have three children and they vaccinated the first two as planned. And then since COVID, with their third child, they're like, 'I don't know if this is safe.' I want to wait until the kids are older,' or 'instead of doing two shots today, I want to do one shot,'” Ball said. “It just prolongs the time that you have an unprotected child and they can potentially get sick from these diseases.”

He goes out of his way to explain to parents the importance and safety of vaccines, including MMR. He even brings up his own children's immunization records to make his point, and often succeeds. But not always.

At Children's Hospital Los Angeles, attending pediatrician Dr. Colleen Kraft said about half of parents question the CDC's recommended vaccine schedule, a significant increase since the pandemic.

“Even my most reasonable parents ask questions. So it’s definitely in the mainstream,” she said. He is also concerned about his patients who are behind on vaccinations because they missed many appointments during the pandemic and are only now returning to his office.

Karla Benzl holds her son, Marcus, 15 months, before he gets vaccinated at Southern Orange County Pediatric Associates in Ladera Ranch on February 28.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

In Marin County, requests from parents to delay vaccinations have become so frequent that Dr. Nelson Branco said last month his office decided to tighten vaccine requirements as cases of measles and whooping cough. Babies seen by doctors at the practice will need to have their first series of vaccinations completed by 4 months of age. The primary series of vaccines against the most serious and common diseases, including measles, should be completed before 24 months.

If parents do not agree, they should abandon the practice.

“Children do many high-risk things before the age of five and must be vaccinated to attend kindergarten,” Branco said. “They take international flights, they go to Disneyland, where there are a lot of children,” leaving young children vulnerable to measles when they could be protected.

The CDC recommends that the first dose of MMR be given when the baby is between 12 and 15 months old. This usually happens at a 12-month-old child's well-child visit. A second dose is then given between 4 and 6 years of age.

At least 95% of people in a community must be vaccinated to reach a level of “herd immunity” which protects everyone in a community, including those who cannot receive the vaccine because they are too young or immunocompromised, according to the World Health Organization.

Low vaccination rates have led to measles outbreaks in several states over the past decade, most recently in Florida.

Nationally, the rate of kindergartners fully immunized against measles fell from 95% in the 2019-20 school year to 93% in 2022-23, according to the CDC.

But overall there is good news in California. Since the state banned parents' personal beliefs as a reason for not vaccinating children before school in 2015, the measles vaccination rate for kindergartners has increased from 92% in the 2013 school year. -2014 to 96.5% in 2022-2023.

Are you a Southern California mom?

The LA Times Early Childhood team wants to connect with you! Find us in The Mamahood moms group on Facebook.

Share your perspective and ask us questions.

But vaccine procrastinators have created a potential vulnerability gap in a child's first four years.

One in five unvaccinated people who get measles in the US will be hospitalized. Since there is no good treatment for measles, doctors can often do little more than offer supportive care. One in every 1,000 children with measles will develop brain inflammation that can leave the child deaf or with an intellectual disability; According to the CDC, between 1 and 3 children in every 1,000 will die.

Measles is so contagious that 90% of people close to an infected person will get it if they are not immune, according to the CDC. The virus can remain contagious in a room or on a surface for up to two hours after the infected person has left.

In Children's Hospital Orange County's primary care network, which has more than 130 pediatricians, the proportion of 15-month-olds receiving the MMR vaccine has steadily declined in recent years, from 98% in 2019 to 93.5%. in 2023.

For years in the early 2000s, anti-vaccine sentiment was at an all-time high after the publication of a now-debunked and retracted study that falsely linked the MMR vaccine to autism. In December 2014, an unvaccinated 11-year-old boy was hospitalized with measles after a visit to Disneyland. Over the next few months, measles spread to 125 people in seven states.

The outbreak helped galvanize support for vaccination across the country. A year after the Disneyland outbreak, California passed a ban on the personal exemption.

“The pendulum swung the other way and we had some years where vaccination rates were really high,” Ball said. But the rumors and rhetoric around COVID vaccines have swung the pendulum in the other direction. “We're back to dealing with conspiracy theories, things people heard on the Internet or something his cousin's neighbor's roommate said. It is very difficult.”

Noah, who is 9 months old, has his measurements taken by physician assistant Shellee Rayl at Southern Orange County Pediatric Associates in Ladera Ranch on February 28.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

A Pew Research survey conducted in March 2023 found that 88% of Americans trust that the benefits of an MMR vaccine outweigh the risks, a percentage that has remained fairly constant since before the pandemic.

But support for all school vaccination mandates has waned; 28% now say parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their children, even if it causes health risks to others, up from 16% in October 2019. Among Republicans, the share has more than doubled , from 20% in 2019 to 42% in 2023.

The survey found that support for the MMR vaccine was lowest among parents with young children. About 65% of parents with children under 5 years old reported that the preventive health benefits of MMR were high (compared with 88% of all adults), and 39% said the risk of side effects was medium or tall; half said they were concerned about whether all childhood vaccines were necessary.

Tara Larson, a former emergency room nurse who lives in Santa Monica, said she was concerned about childhood vaccinations when she was pregnant last year. She began watching anti-vaccine documentaries, reading pamphlets on vaccine safety, and following various social media accounts “to become an informed vaccinator. We are not anti-vaccines,” she said.

Larson decided she wanted to delay vaccinating her son until he was 3 months old, limit him to just three vaccines in his first year that she considered essential, and spread them out so he only received one shot per month. “By the time he starts playing on the playground and going to school, he will need to start his hepatitis B treatment, but why overload his treatment with vaccines right now?” she said.

The first pediatrician he saw refused to follow the requested schedule. But, Larson said, “deep down, I felt like this was the right thing for our baby, and I left.” After weeks of searching, she found a holistic provider who charges a monthly fee of $250 and agreed with her approach.

She said she hasn't decided yet whether to give her son, now 8 months old, the MMR vaccine when he's eligible. “I think some doctors will say to wait until she's 3, but that was when there was no measles resurgence,” she said. “That's what I'm going to dive into next.”

Karla Benzl of Mission Viejo comforts her 15-month-old son Marcus after receiving his vaccines.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

But there is no scientific basis and no known benefit to delaying vaccinations except in very rare medical circumstances, said Casares, whose pediatric practice is in Oregon.

Casares said the problem is that parents have an “exposure bias.” They often consume an avalanche of information on social media about the risks, but very little about the benefits of vaccines or the enormous risks of the diseases themselves. She said that in a country like the United States, where vaccination rates are quite high, most people don't see the havoc that diseases can wreak if rates drop.

This article is part of the Times' early childhood education initiative, which focuses on the learning and development of California children from birth to age 5. To learn more about the initiative and its philanthropic sponsors, visit latimes.com/earlyed.