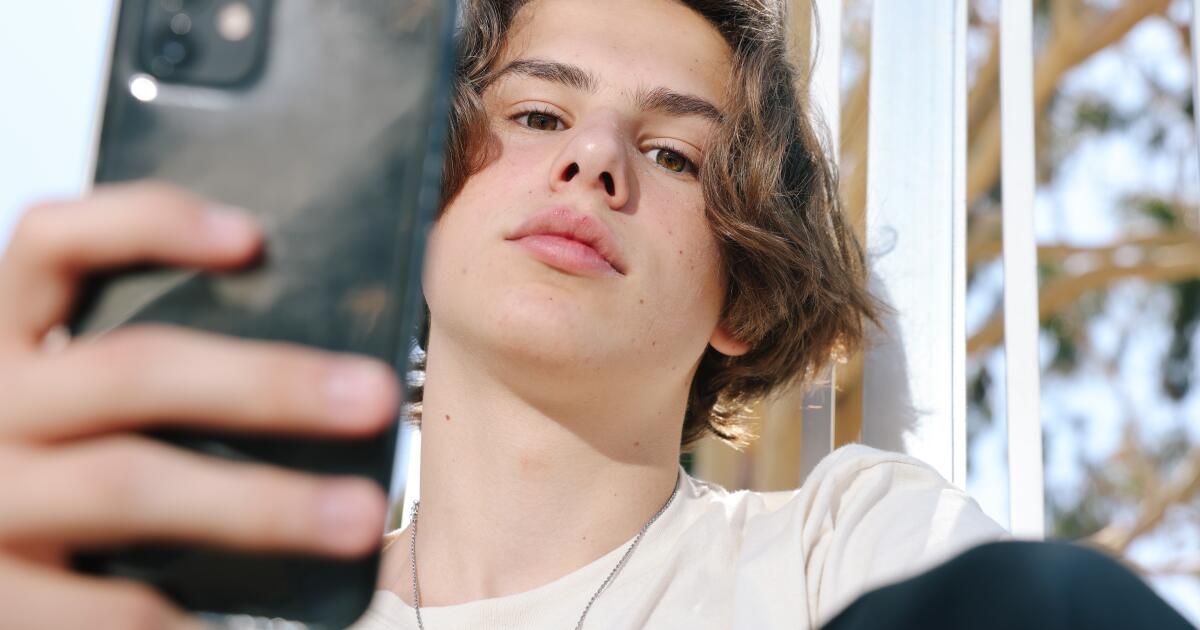

Since William Schnider received his first iPhone in sixth grade, it has become an extension of his being. By day, it’s in his right pants pocket; by night, it’s within arm’s reach. He rarely talks to people on the phone; instead, he communicates through Instagram groups, TikTok memes and text messages. He syncs his calendar with his parents’ phones.

So when William, a 17-year-old senior at Van Nuys High School, heard that cell phones would be banned in all Los Angeles public schools, he immediately scoffed, like so many others.

“I don’t see how it would work,” he said. “I don’t see how it would be fair. Is it necessary?”

But after the initial shock and resounding response from many teenage students, more nuanced thoughts emerge: Maybe we're falling into social media and cellphone addiction. Maybe all the distractions and obsession with “likes” are bad for us. Maybe we need some relief.

William Schnider is in the Van Nuys High School Medical Careers Magnet Program.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

The Board of Education’s 5-2 decision to ban cellphones beginning in January 2025 is intended to change the behavior of a generation of students and will be one of the most significant and closely watched changes in education since students were forced to attend classes online, many by phone, more than four years ago at the start of the pandemic.

Details, such as how the policy will be enforced and where phones will be stored during the school day, will be worked out in the coming months. But the goals are clear. School leaders say they want to combat classroom distractions that impede learning and reduce the dangers of social media addiction. At this point, leaders say, a strict ban on phones is the only way to get students talking to each other and their teachers and to come to value face-to-face conversations over digital connections.

“I understand the intent of the ban,” said Schnider, who is in a medical careers major program and wants to become a physical therapist or physician assistant. “I definitely think phones can be addictive or distracting. It can be very easy to just hyper-analyze what you’re posting on social media. People — me — fall into that trap very easily. They start basing their self-worth on how many likes they get on their stories, how much their friends comment — things that aren’t that important.”

He's caught himself endlessly scrolling through Instagram or repeatedly checking how many people liked a story he recently posted of him and a friend on an outing to see “Inside Out 2.” He's seen students in class turn to their phones when math instruction gets tough.

He has also enjoyed finishing his assignments early during English class and then playing the word game Connections with his friends, without any objections from teachers. Students with good grades like him, he said, don’t need to be banned from using the phone. When two students were stabbed on campus in November and the school was put on lockdown, William texted his mother to say he was safe. He wonders how emergencies will work without that option.

“For people with problems, this won’t end any addiction,” Schnider said. “If you want to be addicted to your phone, you will be.”

Los Angeles is joining a growing movement in K-12 education to ban phones and has won support from Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has backed a bill to make such a rule statewide. Last year, Florida passed a policy to ban student cellphones in all K-12 classrooms. A similar law is set to go into effect in Indiana next year. In Ohio, new legislation will require schools to design policies to “minimize student cellphone use.” New York City, the nation’s largest school district, is set to introduce a student cellphone ban similar to Los Angeles’ this month, after lifting a previous ban in 2015.

For Angelica Zamora-Reyes, a 17-year-old senior at Downtown Magnets High School, the ban can’t come soon enough. She was among dozens of Los Angeles students interviewed by The Times who expressed relief.

When her parents gave her an iPhone for her birthday three years ago, Angelica was excited because she was one of the last in her group of friends to receive one. Over time, she learned to see the pros and cons of digital devices.

Angelica Zamora-Reyes, 17, pictured using her iPhone at her Los Angeles home on July 2, 2024, will be a senior this fall at Downtown Magnets High School. She supports a future school district policy banning students from having cellphones during the day.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

When Angelica took the public bus to an internship this summer, she texted her parents along the way to let them know she was okay. She has an Instagram account to connect with friends and watches YouTube videos, including campus tours and vlogs from students at USC and Harvard, her dream colleges. She also watches online math tutorial videos on Khan Academy.

Through her phone, Angelica, who lives near historic Filipinotown and is the daughter of Mexican immigrants, found new ways to learn and expand her world beyond her corner of urban Los Angeles.

But she also saw the downsides of cellphones. Girls at her school can be “obsessed” with social media, comparing their clothes, weight and followers to those of other teens, she said. She recently looked at her screen-time tracker — 2.5 hours a Thursday afternoon in June — and felt accomplished, in contrast to a cousin whose daily use was several times higher.

Angelica tries to keep her phone in the side pocket of her backpack during the school day. But even though she avoids using it, she gets distracted by other students who do use it.

She recalls an incident last year when a teacher in an Advanced Placement class gave instructions for an assignment, but she could barely hear them over the loud, constant laughter of two classmates engrossed in their phones.

“Not only was it distracting, but it also seemed disrespectful to the teacher and any other students,” Angelica said. She remembers wishing every class was like AP English, where her teacher banned phone use during class.

By the last semester of her senior year, that wish will come true.

But thinking about it, she also has questions. Could she pull out her phone to take pictures of her friends at lunch, like she used to do last school year? Could she still use her phone occasionally in class to take pictures of the whiteboard instead of taking notes?

According to the approved ban, the answer is no. However, Los Angeles school officials said students will be included in policy-making and enforcement that will be presented to the school board in the fall.

“As much as it would be good to ban phones, I see the positive side of having them,” Angelica said.

When another student at her school, Noreen Baig, first heard about the ban (via an Instagram post her mother sent her via cell phone), she thought it was a hoax.

“A blanket ban is not right,” said the 11th grader. Some of her classes already ban phones.

She also worries about emergencies. Last year, her school had several closures, and each time, she texted her mother to check on her.

“Are we all supposed to run to the office to make a phone call?” Baig said. She also uses social media to find out when and where school clubs meet. During lunch, she finds her friends in the cafeteria through Instagram messages.

“My phone is a part of me,” Baig said. “LAUSD is trying to solve a small problem by taking technology away from everyone.”

For many students, the reality of what a cell phone ban will mean is difficult to grasp.

But that wasn't the case for A Quindel Peral, an eighth-grader at Mark Twain Middle School.

Her mother, an algebra and data science teacher at Venice Middle School, was part of a team of teachers who started a phone-free school program in March. A wears a Gabb watch to school, a simpler version of an Apple Watch that is designed to have limited features (GPS and texting among them) so parents can stay in touch with their children. At home, A has access to a Wi-Fi-enabled iPad that she uses to text friends and play chess and Wordle.

Quindel Peral will be in eighth grade this fall at Mark Twain Middle School. Pictured here at her home in Mar Vista, she supports a cell phone ban in LAUSD.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

She is one of two people in her high school friend group who doesn't have a phone. At first, A felt left out, even angry. Her parents say she'll get a phone when she starts high school, at which point the no-school-day policy will be in effect.

But by going to school without a phone, A noticed that he acted differently than other students. He could concentrate better and longer on assignments and reading. He noticed that some classmates hid their phones behind books during class, pretending to read while actually texting and browsing. With his mother’s support, he began to learn more about teenagers and technology.

“Kids are at a critical stage of their growth right now, basically. They are at a time in their lives where their brains are growing a lot. They are more susceptible to peer pressure,” she said. “It’s very important that we don’t abuse the power that phones give us. It really depends on how we use them.”

Still, she is looking forward to having a mobile phone when the time comes, but she no longer counts the days like she used to.