Cal State Northridge researchers this week released the first city-sponsored report on potential reparations to Black residents for the discriminatory harms they faced over the past 100 years.

Documenting the struggles of black Angelenos from 1925 to today, “An Examination of African-American Experiences in Los Angeles” is a 400 page report Created by the Advisory Commission on Reparations from the city's Department of Civil + Human Rights and Equity in collaboration with the university.

Six CSUN researchers interviewed and conducted focus groups with hundreds of residents, past and present, and analyzed laws and public policies from the past century to determine the effect of racial discrimination on the descendants of enslaved African Americans.

“Despite the legal end of slavery, Black Angelenos continue to face systemic discrimination and inequity through legal segregation, enacted both by the state through the Los Angeles Police Department and the courts, and by the public, including groups like the Ku Klux Klan,” said researcher Marquita Gammage, a professor of Africana studies at CSUN.

Twelve types of harm were documented: vestiges of slavery; racial terror; mental and physical harm and neglect; racism in the environment and infrastructure; an unjust legal system; housing segregation; stolen labor and hampered opportunities; separate and unequal education; political disenfranchisement; pathologization of the black family; control over creative, cultural, and intellectual life; and the wealth gap.

The researchers provided three potential remedial solutions for each harm listed. In the case of housing segregation, Gammage says the city should “count the cost of housing inequity and put in place compensatory initiatives, fund and support programs that advance equity and homeownership opportunities, and proactively address homelessness and housing insecurity among Black residents.”

Radio personality Dominique DiPrima speaks at the session.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

According to the report, approximately 80% of respondents supported homebuyer assistance, appraisal protections to prevent overpayments, and programs to address housing insecurity. A total of 618 people were interviewed for this report, and more than half were women.

Most respondents expressed interest in monetary reparations, the researchers found.

Marisa Turesky from Mockingbird Analytics She gave a presentation on successful monetary reparations in U.S. cities such as Evanston, Illinois, which provided a $25,000 payment from a cannabis sales tax to black residents who experienced housing discrimination between 1919 and 1969.

“Any reparations program really needs to prioritize Black people who govern the money and decide the policies around its use,” Turesky said.

The Reparations Advisory Commission is expected to enter its fourth phase this fall, working to craft recommendations for Mayor Karen Bass on how the city should address reparations for Black people.

The commission was created in 2021 under then-Mayor Eric Garcetti to develop and recommend reparations for Black Angelenos by seeking opportunities to fund reparations, as well as identifying an academic partner to assist in program development.

As part of the research, CSUN and LA Civil Rights created a timeline of city policies that contributed to the erosion of Black rights from 1930 to the present.

Launching the report on Tuesday night, W. Gabriel Selassie said he was shocked by its findings on the level of oppression and described some of the many ways it manifested itself in everyday life.

“You go out on the street and you open your car door as an LAPD car drives by. You put your stuff in the car and the police car backs up,” he said. “The next thing you know, you’re in a jail cell … brutally beaten. You have a court hearing and the judge dismissed the case. Now you’ve lost your dignity, your pride, your time on the job; you’re scarred for life. Those kinds of things I saw, things that were documented by defense attorneys who were seeing this kind of racial injustice and were so outraged by it, they collected personal data and eventually turned it over to news agencies or just kept it in a file.”

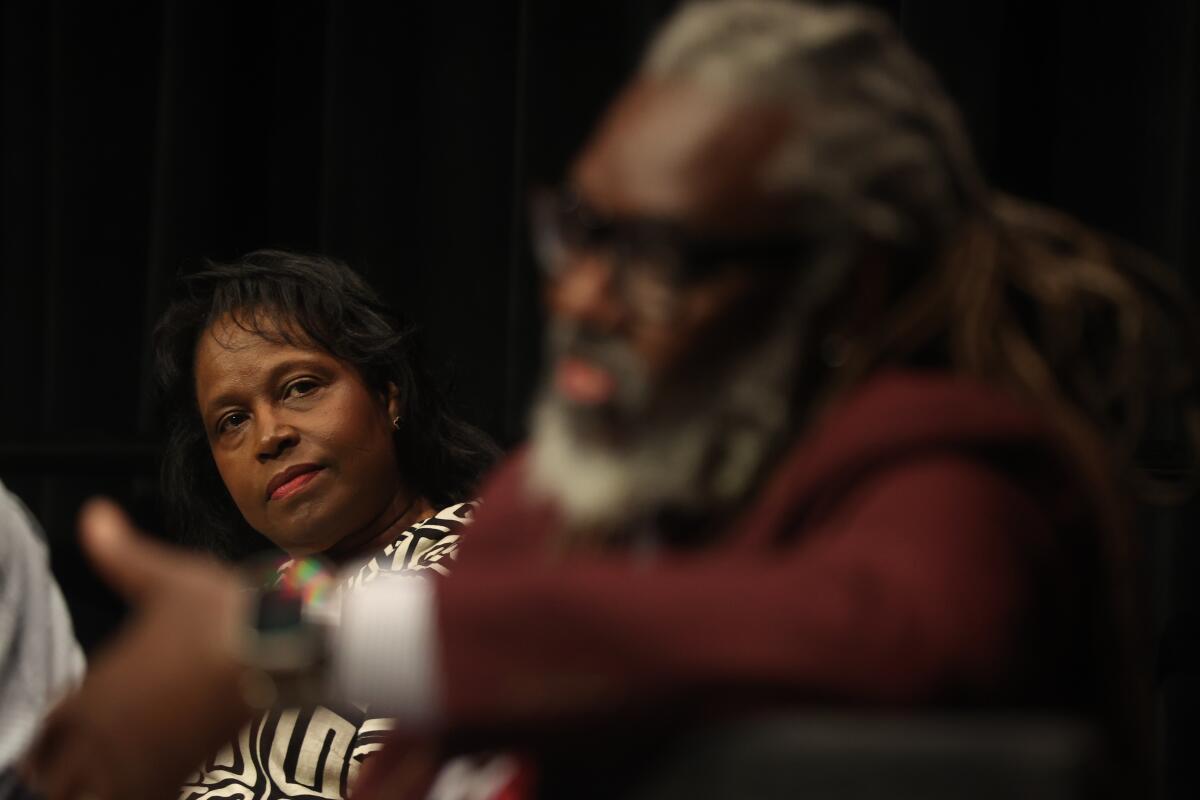

Karin Stanford listens to Cal State Northridge professor W. Gabriel Selassie during the discussion.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

Gammage described open racial violence, “including lynchings, burning and destruction of homes, physical assaults… since the founding of Los Angeles.”

The report found that housing discrimination continues to disproportionately affect black residents.

“We found that Proposition 14 in 1964 repealed the Rumford Fair Housing Act of 1963 and reinstated discriminatory practices in Los Angeles neighborhoods that restricted Black residency in those neighborhoods, leading to further equity growth,” Gammage said. “Segregation and housing policies historically limited Black wealth accumulation through homeownership, with 68.3% of white households owning homes versus only 41.5% of Black Angelenos owning homes.”

Researchers found that 40,000 black people living in Los Angeles were confined to Central Alameda, South Park, and Watts in 1930 due to zoning practices, restrictive covenants, and residential segregation policies that prevented them from moving to new neighborhoods.

By the 1960s, Los Angeles's black population had grown to 350,000, and many families expanded into predominantly white neighborhoods in South Los Angeles.

However, racial integration never occurred successfully, resulting in areas of black “ghettoization” throughout the city and beyond, not only in South Los Angeles, but also in Inglewood, Compton, and Venice.

In the San Fernando Valley, black families were limited primarily to Arleta and Pacoima.

“The vast San Fernando Valley region was always the area of Los Angeles that most vehemently opposed integration,” the timeline notes. “In 1970, while the Valley had a total population of nearly a million people, there were only about 18,000 black people. These areas were older sections of the Valley where restrictive covenants did not exist or were not enforced.”

Karin Stanford, a professor of political science and Africana studies at CSUN, said the report is a record of wrongs facilitated by the city and provides steps toward reparations.

“Los Angeles is a city of angels, and angels are messengers,” Stanford said. “And we’re sending a message to the entire United States of America that we stand strong in this space.”