Staff members at Frank Del Olmo Elementary School were taken aback when I asked them about the name of the school.

After all, his name was all around us. In the whimsical book mural, a falcon (the school mascot), a quill pen and an inkwell with the motto “Make a difference in the world.” On school t-shirts advertised for sale on banners in English and Spanish hanging from a fence. In the elegant, framed city proclamation signed in 2006 by then-Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa to mark the opening of this two-story, three-acre square school on the outskirts of the historic Philippine city.

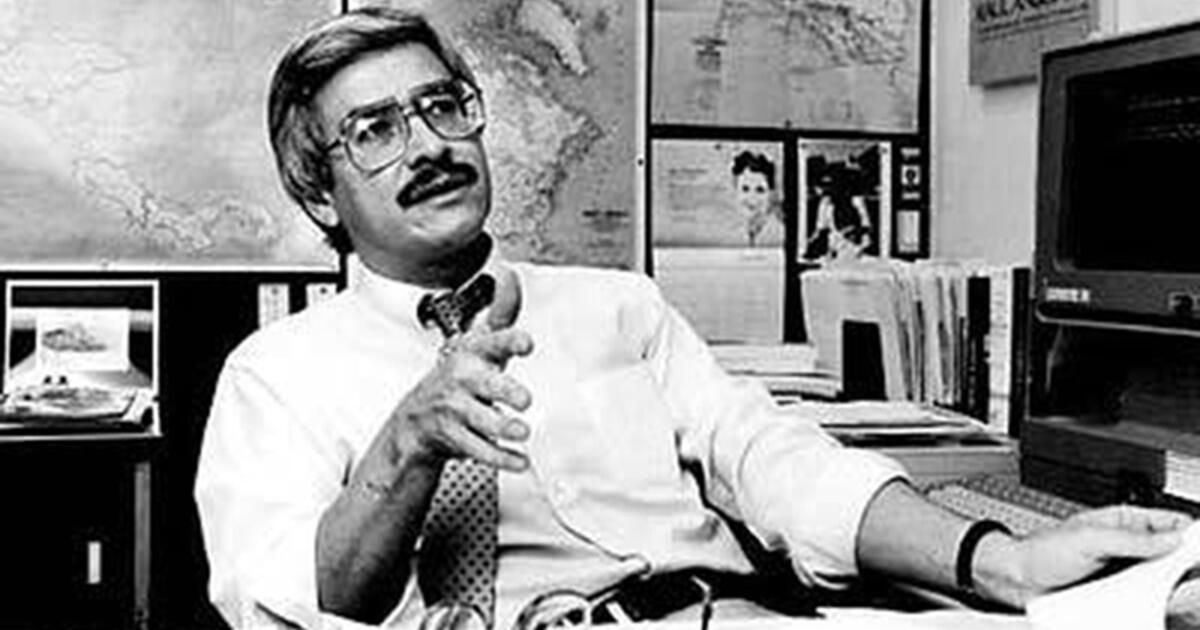

But I couldn't find much that told the world who Frank del Olmo was. was. A pioneering Los Angeles Times reporter, columnist and editor. The first Latino on the newspaper's masthead. Founding member of the California Chicano News Media Association. A member of the National Association. of the Hispanic Journalists Hall of Fame. A veteran defender of the oppressed and an obstacle to the powerful.

I visited Frank del Olmo Elementary on Tuesday to pay my respects, a day after the 20th anniversary of his death from a heart attack at age 55 outside his office in the former Times headquarters downtown, which sparked protests. condolences from the then Mexican president Vicente Fox and the Nobel Prize winner. Gabriel García Márquez Award. At Del Olmo's funeral, then-Times editor John Carroll told an audience of nearly 900 that the newspaper and Los Angeles would “always remember” Del Olmo.

We did not.

The only hint of Del Olmo's accomplishments I could find was in that mural facing Vermont Avenue. Under his name was the word “journalist.” The inkwell bore a faint outline of the Pulitzer Prize medal, which he and other employees won in 1984 for a groundbreaking series about Latinos in Southern California.

I thought I would find more at the entrance to the school, where there were two plaques bolted to columns. No. A plaque commemorated “the Americanization of Godzilla,” which took place in 1956, when footage for the English-language version of the monster classic was filmed here. The other greeted the company that finished building the school, more than a year late.

Then a secretary remembered that there was something crossed out on the sidewalk, right in front of the attendance office. I left quickly. A concrete slab had the name of founding principal Frank del Olmo Elementary School and his handprints.

Del Olmo never entered the public consciousness like his predecessor, Rubén Salazar, the Times columnist killed in 1970 by a tear gas canister fired by a Los Angeles County sheriff's deputy during the Chicano Moratorium in East Los Angeles. Del Olmo's work is barely recorded in journalism schools today. This newspaper long ago finished its Frank del Olmo Impact Award for a high school newspaper whose work made a difference in the community. One of the only traces of him in the world of journalism is a scholarship in his name from CCNMA: Latino Journalists of California. A friend had to remind me that Monday marked 20 years since Del Olmo's death, and then I had to remind my colleagues.

Unfortunately, obsolescence is the fate of most journalists. We write our stories, we wait for a reaction from readers that often does not come, we move on to the next article. Our clips inevitably gather literal and digital dust, remembered only by a few. And that is a career.

It is a fate that Del Olmo does not deserve. He and the late Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl are the only journalists to have a Los Angeles Unified school named after him. It is thanks to Del Olmo that The Times has as many Latino reporters and editors as we do. He fought for representation in the newsroom and in our stories until literally the end of his life. That day, Del Olmo was supposed to have lunch with Latino staff to discuss how management could better support an initiative to cover Latinos, recalled former Times editor Frank Sotomayor and current Times editors Steve Padilla and Nancy Rivera. Brooks.

We've never commemorated the anniversary of Del Olmo's death in the five years I've been here: not a Slack post, not a company-wide email. nothing. So I wasn't surprised that the school had forgotten about it too. If there is little to mark Del Olmo's legacy at the school that bears his name and at the newspaper where he worked, how can we expect the rest of the city to remember him?

The staff called me to return to the office. Waiting for me this time was second-year assistant principal Veronica Ciafone.

“I didn't know who Frank del Olmo was before I moved here, so I read everything about him,” the 45-year-old South Los Angeles native said as we walked across campus toward the library. Someone had mentioned that he thought there was a Del Olmo marker there. “I wanted to understand why they named a school after a person and not a street.”

Just inside the library entrance was a framed yellow sign displaying a black-and-white image of a smiling Del Olmo. “My hope has been to have a career that would allow me [me] make at least a small difference in the world,” he said in Spanish.

“He died young, didn't he?” Ciafone said before asking the librarian if there was anything else. Nothing.

The lunch bell rang. I expected an avalanche of children. She was hoping to ask if they knew anything about Del Olmo. Nobody came.

“Rainy day schedule,” Ciafone said with a smile.

We returned to his office, decorated with memorabilia from his career: photographs, a small Chinese dragon, a USC pennant. He reached into his desk and pulled out a hardcover edition of “Frank del Olmo: Commentaries on His Time,” an anthology of his work published a few months after his death.

“At university we heard a lot about Rubén Salazar, but nothing about Frank del Olmo,” he admitted. “Even where I was before, I remember there was a Rubén Salazar scholarship.”

Ciafone searched his laptop. She showed me a brochure for it.

“It's unfortunate,” said the daughter of Mexican immigrants, “because Frank del Olmo's contributions to Latinos were obviously significant as well.”

He was more than just a Latino figurehead, I responded. Del Olmo is pigeonholed as a Chicano voice, but he was a Los Angeles voice, period.

Frank del Olmo, wearing a black jacket in the back row, with members of the Times team that won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 1984. Bottom row, left to right: David Reyes, Virginia Escalante, Louis Sahagún. Back row, from left, George Ramos, Noel Greenwood, Frank Sotomayor, Del Olmo, José Galvez and Robert Montemayor.

(Los Angeles Times)

He wrote about the secession struggles in his native San Fernando Valley and the rise of the labor movement in city politics. He criticized this newspaper for supporting Pete Wilson's re-election in 1994 after the California governor linked his campaign to the harmful Proposition 187. Police brutality, civic corruption and even sports: Del Olmo covered it all in a taut, thorough style.

But his most beautiful columns, I told Ciafone, were those about his son, Frankie. Every December for a decade starting in 1995, he told readers about Frankie's life with autism, beginning with the boy's diagnosis at age 3. In a dispatch that Del Olmo wrote two months before his death, he announced that “the two great gifts” he could give his son “are my presence and his privacy. And he will have both.

Ciafone flipped through some of those Frankie columns. His eyes widened with each page. Then it came to the end, an excerpt from an assignment Frankie did about his father.

“My dream is to be able to be a great man like my dad,” the vice principal read aloud slowly, “so I can do good things like him.”

He closed the book and wiped his eyes.

As we said goodbye, I asked if there was any chance the students could learn more about Frank del Olmo. She thought about it. “In a few months we'll be celebrating Career Day, so it would be nice to honor that.”

“Are you going to have a reporter?” I blurted out.

Ciafone smiled.

“Can we, would you like to come and tell our students about Frank del Olmo?”

It would be an honor for me.