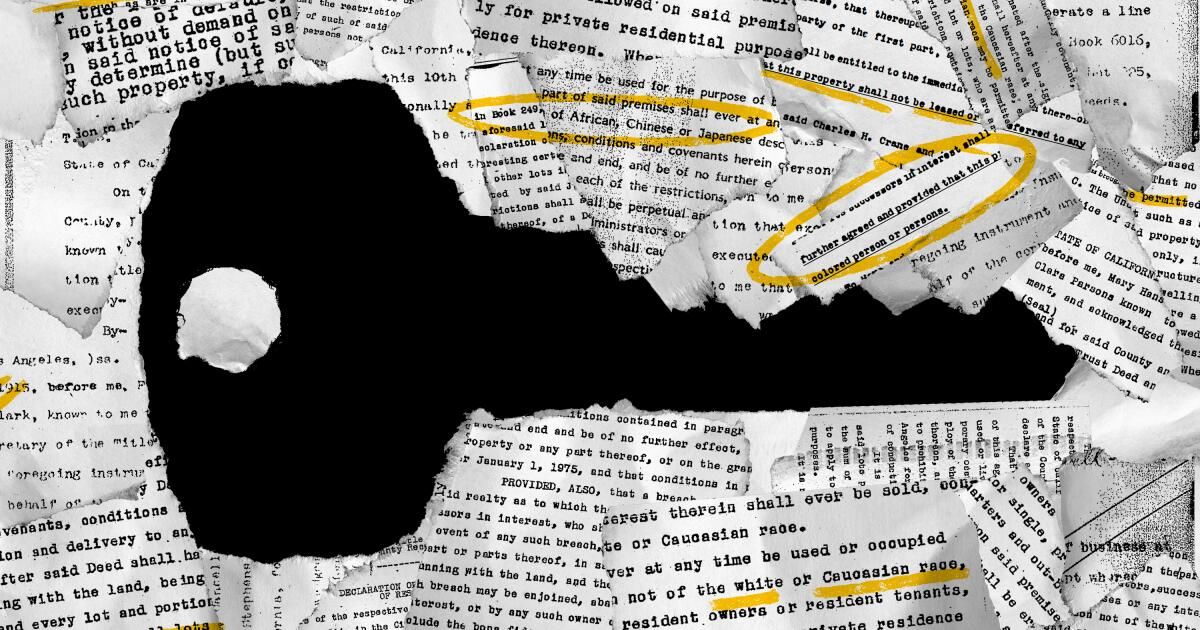

The requirements for living on the San Fernando Valley lots were clear in 1915.

Any building, including the roof, must have two coats of paint. Fences “shall” be stained, painted or whitewashed.

On the heels of a ban on liquor sales, the land record for the Los Angeles Farming and Milling Co. Rancho subdivision required that “no part of said premises shall be sold, conveyed, leased or rented at any time to any person of African, Chinese or Japanese ancestry.”

Racially restrictive covenants like this were common in Los Angeles County in the early 20th century and ended only after the U.S. Supreme Court and federal law prohibited their enforcement. But if you buy a home in Los Angeles County today built before 1968, you'll probably still see the language in your property records. But that will soon change.

In response to a new state law, Los Angeles County hired a firm for about $8 million to redact racially restrictive covenant language for millions of county records. The process is expected to take at least seven years and begin this year.

“It's part of a stain on our history, of discrimination and racism,” said Los Angeles County Recorder/Clerk Dean C. Logan. “I think for me and for the county, this represents a form of recognition.”

Logan said the company, Wisconsin-based Extract Systems, and the county will work together to search and review the entire archive, which dates back to 1850.

An estimated 130 million documents (about 460 million pages) will be examined, Logan said.

About 90 million of those documents are in digital format, which will allow its contractor to use automation to look for racist language. But the other 40 million records (dating from 1850 to 1976) are recorded only on paper, books or rolls of microfilm. It will take a “human operator and the use of technology” to redact the racist language in those documents, Logan said.

Workers will start with the most recent documents, those that are in digital format, and work backwards. The original documents will still be available for inspection, but the version seen by owners will have a black bar over the language, Logan said.

The seven-year schedule is based not only on workload but also on how much money the county gets from a new $2 document recording fee, which state law allows to be charged through 2027, unless extended .

For years, homeowners could request that the county remove a racially restrictive covenant from their records at no cost. That process is still available.

“Moving that language in the legal description into future recorded documents is almost a passive acceptance of that, and those restrictive covenants were prohibited and serve no useful purpose in documents moving up the chain of title,” Logan said. “I think the impact of doing this is that it removes that language, but it doesn't remove it from the story.”

Los Angeles County Supervisor Holly J. Mitchell, who introduced a bill removing “lynching” from California law during her tenure in the state Senate, said that regardless of its applicability, the language in Laws matter.

After her grandmother died, Mitchell was going through her family's paperwork, badgering her great-aunt to write a will to protect the Exposition Park home she bought decades ago.

Mitchell pulled out the deed and was stunned when she saw text prohibiting black people from living in the house her family had lived in for years.

“Reading it I thought, 'Oh my God, this is what I read about,'” Mitchell said.

Historian Laura Redford, who completed her doctoral work at UCLA on racially restrictive covenants in Los Angeles County, said the first she encountered realtors or developers using restrictive covenants in the county was in 1908, as developer Lawrence B. Burck, who announced ''Armored Racing Restrictions'' in two areas about 20 blocks south of Exposition Park.

Redford, a visiting assistant professor at Brigham Young University, found in her research that in 1939, 47% of residential neighborhoods in Los Angeles County “had restrictive covenants that prohibited certain racial groups from remaining in those communities,” according to her thesis. .

Newsletter

Get all the information on Los Angeles politics

Sign up for our Los Angeles City Council newsletter for weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Conceptually, restrictive covenants exist to describe what owners can do with their property, such as stable their horses or other typical restrictions, Redford said.

But real estate agents and developers used them not only to exclude people of color but also to dictate the class of residents by specifying the minimum amount residents must spend to build, and even the size of the house.

As a historian, Redford said she fears that removing the covenant's restrictive language from land records probably won't cause history to repeat itself in terms of such blatant racial restrictions, but it does raise concerns about whether people will understand how those policies also separated people. per class.

Redford said the Supreme Court, in its 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer decision, ruled that states advocating racially restrictive covenants violated the 14th Amendment, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited racist policy, but that issues related to class in housing law persist.

“We continue to segregate by class; we do it by selling at prices… saying, 'This is a community of single-family homes valued so much,' and we can't put an apartment building in it because it will destroy the value of the single-family homes.” Redford said. “We have done a less than good job as a society of addressing the class segregation that we continue to perpetuate.”