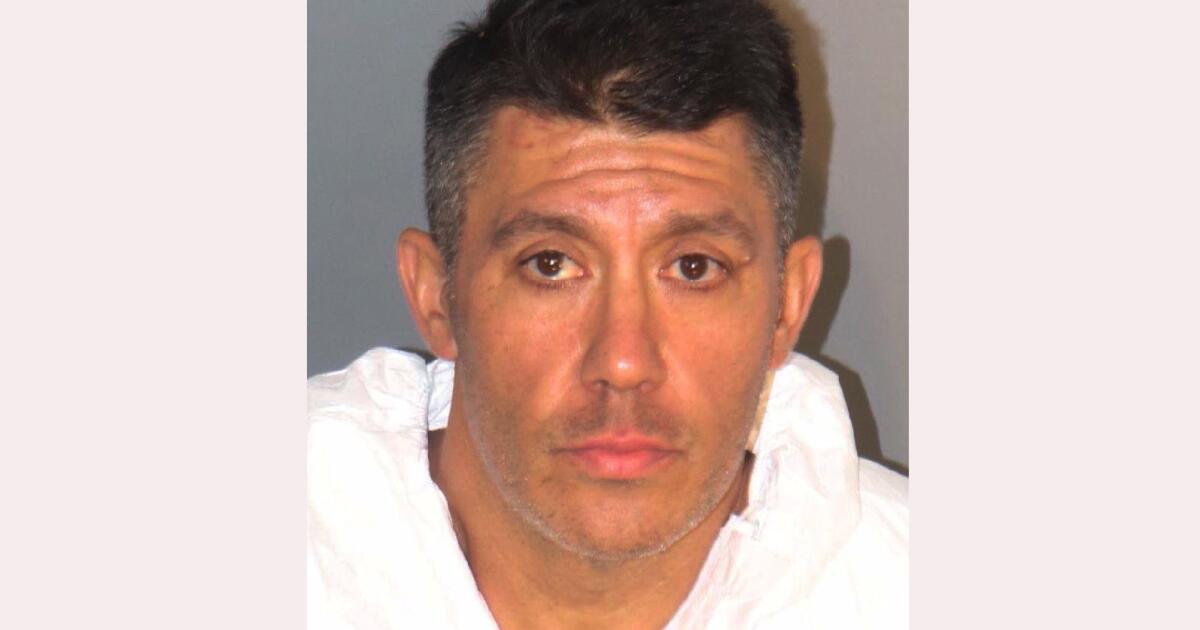

From morning to evening, six days a week, Gustavo Reyes González spent his days cutting artificial stone, a man-made product that has become a popular choice for kitchen and bathroom countertops.

Glossy plates are stain-resistant, highly durable and come in many colors. They are also full of crystalline silica – tiny particles that can cause irreparable scarring of the lungs when inhaled.

By the time Reyes Gonzalez was 33, his lungs had been ravaged by silicosis, an incurable disease. He was forced to rely on an oxygen tank and grew thin and weak. At one point, he said, he asked God to take his life so that his suffering would end.

His doctor says the 34-year-old is only alive today because he had both lungs replaced in a transplant, and that the painstaking surgery can only give him another six years to live.

“We don’t know how much time he has left with that lung,” his wife Wendy Torres Hernandez told a Los Angeles courtroom. After the transplant, he must take a series of medications, restrict his diet and closely monitor his blood pressure and sugar levels.

All of those measures, he said, “will continue until he dies.”

In Los Angeles County, a jury will weigh in on a question that could reverberate throughout the stone industry: Are corporations that manufacture or distribute engineered stone to blame?

Health researchers have linked the rise in silicosis cases among countertop cutters to the growing popularity of engineered or artificial stone, which typically has a much higher silica content than natural marble or granite. In California, dozens of workers with silicosis have filed lawsuits against companies including Cambria and Caesarstone.

Reyes Gonzalez is the first of them to go to trial, according to his attorneys. The Los Angeles County civil case poses a test of whether companies that make artificial stone could be held liable amid the devastating rash of silicosis, which has killed more than a dozen countertop cutters across California in recent years.

Dr. Robert Harrison, a professor of occupational medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who has researched silicosis among countertop cutters, said a decision in favor of the plaintiff “would send a message to manufacturers that they are responsible for producing a toxic product like engineered stone.”

Regardless of the outcome, Harrison said the court case “brings a spotlight on the workers behind the products we buy.” That could reinforce public awareness that “there are workers making our products who are getting sick and dying,” she said, and hopefully inspire new efforts to stop it.

Marissa Bankert, executive director of the International Surface Manufacturers Association, which represents tile-cutting companies, said that “regardless of the outcome of this case, it is essential that all surface manufacturing companies and their employees receive training on and adhere to safety practices.”

In a trial that has dragged on for weeks, Reyes Gonzalez’s lawyers have argued that the manufacturers of the artificial stone failed to give adequate warnings about the dangers of their product. Attorney Gilbert Purcell called it “terribly toxic and dangerous” and “defective in its design,” arguing that its risks far outweigh its benefits.

The question is, “Why not just eliminate this product altogether? Society doesn’t need this product,” Purcell told jurors. “It certainly doesn’t need the carnage it causes.”

Lawyers for the artificial stone manufacturers countered that the fault lay with the operators of the Orange County workshops where Reyes Gonzalez worked. Those “fabrication workshops” cut the slabs made by the manufacturers.

“We know this product is safe,” said Cambria attorney Lindsay Weiss, “as long as it is handled safely.”

Reyes Gonzalez testified that he worked at a series of Orange County shops cutting slabs of artificial stone. At times, he said, the air was so dusty it looked like fog. His mask became “really dirty,” he testified. Even when he used water while cutting, Reyes Gonzalez said that after it dried, “a lot of dust would come off.”

Caesarstone argued in court that the company had given the shops all the information they needed to protect workers, including instructions on ventilation and wet cutting to reduce dust. Its lawyer, Peter Strotz, said what happened to the worker was a tragedy, but preventable.

It could have been avoided if “those who owned and operated the fabrication shop where he worked had done what Caesarstone asked them to do,” Strotz argued.

He and other attorneys representing artificial stone manufacturers sought to focus attention on members of the Silverio family, who had paid Reyes Gonzalez for his work at the Orange County stores.

The worker’s attorneys argued that the Silverios were not his employers and that Reyes Gonzalez was an independent contractor. Fernando Silverio Soto, who created Silverio Stone Works, testified that all he knew about the dangers was what he had been told: to minimize the risk by wearing masks and using water while cutting.

Strotz showed the courtroom a Caesarstone form that Silverio had signed, stating that he had received safety information and an instructional video. In court, Silverio denied having seen those materials.

Jon Grzeskowiak, executive vice president of research and development and process operations for Cambria, said the company offers free training to quarrymen and that safety information about its products was available on its website. Fernando Silverio Soto said during his testimony that he had not seen that website nor had he accessed Caesarstone's website to obtain that information.

“I was never told I needed to do that,” he said of Caesarstone’s website.

Defense attorneys also presented expert witnesses who testified that the artificial stone could be safely cut and polished with effective use of workplace safety measures. Reyes Gonzalez's attorneys, in turn, called on experts who questioned whether measures such as masks or the use of water during cutting were adequate.

Among them was industrial hygienist Stephen Petty, who testified that an N95 mask was insufficient to protect a worker from dust generated when grinding artificial stone.

Petty said even the best type of respirator available, which supplies the worker with clean air from a tank, would not work well in the long term because it is so uncomfortable that workers tend to adjust it, breaking the seal.

UCSF’s Harrison, who did not testify in the case, said it is very difficult to protect workers who cut artificial stone. “It takes a lot of money and a very sophisticated and knowledgeable employer, with a lot of expensive machines and ventilation systems to protect workers from exposure to artificial stone dust.”

Safety regulators around the world have had to grapple with the risks of artificial stone as its popularity has soared. In Australia, the government ended up banning artificial slabs amid a public uproar over stonemasons' illnesses and deaths. Workplace safety regulators there called it “the only way to ensure that another generation of Australian workers does not contract silicosis from such work.”

In California, government regulators have stopped short of banning it, instead enacting stricter rules on workplace silica exposure. Another proposal that would have restricted companies that could perform stone carving work was introduced this summer by its author, Assemblywoman Luz Rivas (D-North Hollywood), who said state regulators were “not receptive” to creating a tracking system for licensed shops.

Cal/OSHA officials have warned in the past that if tougher standards don’t yield results, they might move forward with banning artificial stone. In a recent report, however, the agency said it had so far rejected the idea because a ban could encourage “the creation of illegal fabrication shops that are hidden from regulators.”