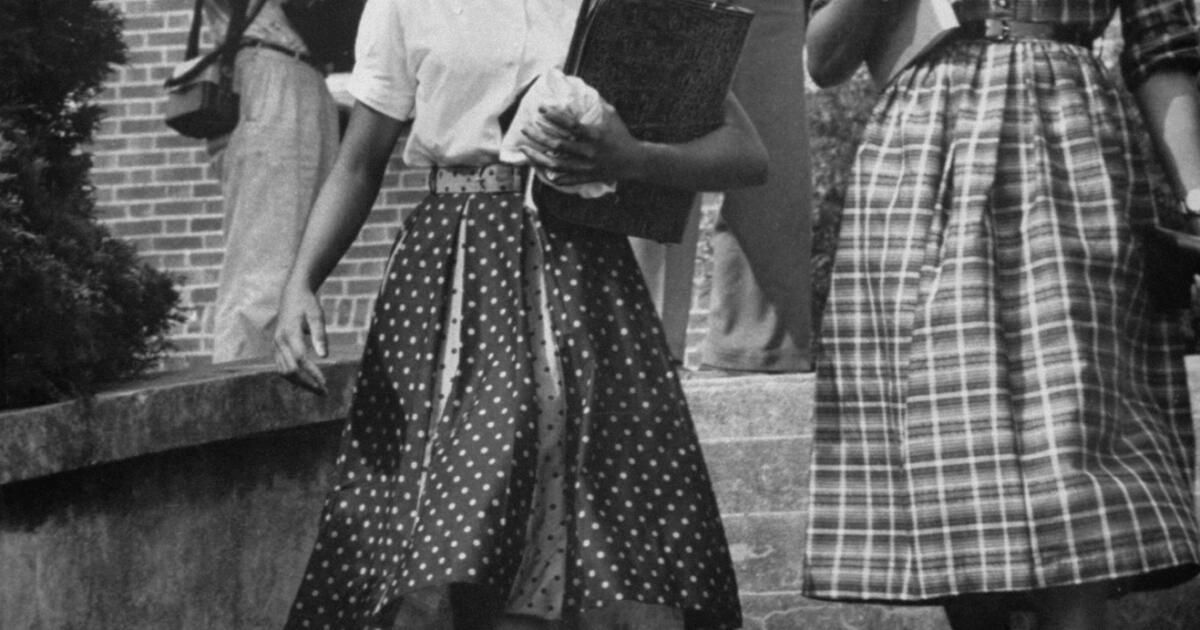

The night before she entered Clinton High School for the first time in 1956, Jo Ann Allen glowed in her outfit with the excitement of any teenager starting the ninth grade.

Her grandmother had sewn the dress: white with careful piping, pleats, and a wide, pressed collar. With her best friend Gail Ann Epps Upton, she talked about clothes, classes, and making new friends.

Allen, ever the optimist, would not have imagined that his daily walk up Foley Hill would soon be met with crowds of jeering segregationists and a bastion of National Guardsmen. At age 14, she was one of the so-called Clinton 12, the first black students to desegregate a Southern public school following the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

“These kids did a grown-up job, basically facing a firing squad every day,” their daughter-in-law, Libby Boyce, said in an interview. “Jo Ann was very positive and strong through it all. It's a testament to her and her upbringing.”

Surrounded by her family at her Wilshire Vista home, Jo Ann Allen died Wednesday of pancreatic cancer. She was 84 years old.

“She embodied positivity and strength,” said Kamlyn Young, Allen's daughter. “She was a lover of people. She loved life and always sought to see the good in people through all the adversity.”

Allen, who later married and changed her last name to Boyce, carried that spirit into every chapter of her life: as a pediatric nurse, a member of the family musical group The Debs and co-author of “This Promise of Change: One Girl's Story in the Fight for School Equality,” which she shared with student audiences across the country.

“We have lost such a kind and humble soul. Jo Ann was someone who was so generous with her own story and shared it with people across the country… She inspired everyone she met,” the Green McAdoo Cultural Center, a museum that preserves the legacy of the Clinton 12, said in a statement.

Jo Ann Crozier Allen Boyce was born in the small eastern Tennessee town of Clinton on September 15, 1941. She was the eldest of three children of Alice Josephine Hopper Allen and Herbert Allen.

He grew up in a modest house with a large kitchen and two bedrooms. Boyce shared a bedroom with his sister, Mamie, which was decorated by their mother with red wallpaper and a small dresser.

An avid student from an early age, Boyce was already reading at age 5 when she entered first grade at Green McAdoo School. She credited her parents and her first teacher, Teresa Blair, for fueling her academic curiosity despite the school's limited resources.

The Allen family's life revolved around the church. Jo Ann sang duets with Mamie at services and looked forward to the Friday night fish fry.

After graduating from Green McAdoo, he rode the school bus with his classmates to a school in Knoxville, 20 miles from his home.

“There were times during those days when we did not make it to school due to bad weather or some other adverse event,” he wrote in a biographical post on the McAdoo Center website.

In 1956, Judge Robert Taylor issued an order integrating Clinton High School following the Brown v. Board of Education. Jo Ann and 11 others would become the first black students to attend.

“When we started school, there were only a few people around. And I thought, 'Well, they're just here to be curious,'” Boyce recalled in a 1956 television interview.

But the next day, segregationists, egged on by Ku Klux Klan member John Kasper, packed the entrance to Clinton High School.

At Clinton High, most people were friendly and curious, Boyce said. But others tormented the 12 children inside: pushing them down hallways, stepping on their heels, leaving threatening notes and even putting thumbtacks in Boyce's chair.

“I started thinking, 'Maybe they won't accept us like I thought,'” Boyce recalled in the interview. “They seemed so mean. It seemed like they just wanted to grab us and throw us out. They didn't love us at all. I could see the hatred in their hearts.”

Violence escalated at Clinton when Kasper was arrested for violating a restraining order meant to keep him away from school. His outraged followers thronged the small town. They knocked down cars with black drivers, assaulted a pastor who preached against prejudice, and beat Upton's boyfriend when he returned to town from a military deployment. Herbert Allen was arrested and later released for defending the family home from cross-burning Klansmen one night.

The chaos led then-Tennessee Governor Frank Clement to send the National Guard to Clinton to restore peace.

But enough was enough. Alice Allen decided it was time for the family to leave Tennessee.

“And what my mother said, we did,” Boyce said in an interview with CBS Los Angeles in 2023.

One winter morning in 1957, local reporters interviewed the family before getting into a car bound for Los Angeles.

“We will not leave here with hatred in our hearts for anyone,” Herbert Allen said. “Even those who are against us… we realize that those people are simply deluded. They were trained and raised that way.”

With the camera now focused on Boyce, he spoke quietly. He talked about the A's and B's he had earned that semester and declared that he had “accomplished something.”

The previous five months had been the most painful of his life, he later said.

“She felt cheated,” Young told The Times. “She wanted to stay and graduate to show everyone that she could do it no matter what. She always had the idea that love would conquer all. That's what guided her for the rest of her life.”

Clinton High was practically reduced to rubble after a bomb attack in 1958. No one was arrested.

Only two of the 12 Clintons would graduate from the school.

The Allen family joined relatives already living in California. Boyce entered Dorsey High School in Baldwin Hills and graduated in 1958. He later attended Los Angeles City College before enrolling in nursing school.

She became a pediatric nurse and worked in this field for decades.

“She always played the underdog and loved kids,” Young said.

Music also attracted her. In Los Angeles, he formed a vocal trio with his sister Mamie and cousin Sandra called The Debs, briefly singing backup for Sam Cooke. Later, he performed in jazz sets throughout the city, from cabaret stages to the historic Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel.

In 1959, she met Victor Boyce at a dance and he “stole her” from the couple she had been dancing with, the family recalled. The couple later married and remained married for 64 years, raising three children and generations of family, including actor Cameron Boyce, who died in 2019.

Her many fans would call her “Nana,” the title Boyce was given by her grandchildren.

Even as she endured breast cancer, a serious stroke, and later pancreatic cancer, her trademark optimism never left her.

“She would come in and just light up the room,” Libby Boyce said. “He had a glow that was nobody's business.”

“Whether because of that amazing optimism or some other higher force at work,” said family member Gregory Small, she had survived pancreatic cancer for 12 years, a feat that stunned her doctors.

The story of the Clinton 12 is not as well-known as that of the Little Rock Nine or Ruby Bridges, other students who integrated into the schools after Boyce. She recognized it and set out to change it: she spent her final years speaking to students across the United States.

She co-authored the book “This Promise of Change” in 2019 with Debbie Levy and worked with the Green McAdoo Cultural Center, located in her childhood elementary school building, to continue the fight for awareness and equality that began when she was 14 years old.

“She used to say racism is a disease of the heart,” Kamlyn Boyce said. “She reached out to them, she didn't walk away. She even loved people with hate in their hearts. That's the only way I can say it.”

Boyce is survived by her three children: Kamlyn Young, London Boyce and Victor Boyce, her sister Mamie, three grandchildren and countless people who affectionately call her Nana.