If a bed in a homeless shelter has been occupied, is that bed still “available”?

Plaintiffs in a five-year-old lawsuit alleging the city of Los Angeles failed to address homelessness say the answer is an obvious “no.” But the city disagrees.

According to testimony from city administrative officer Matt Szabo, a bed created by the city remains “on sale” whether someone sleeps in it or not.

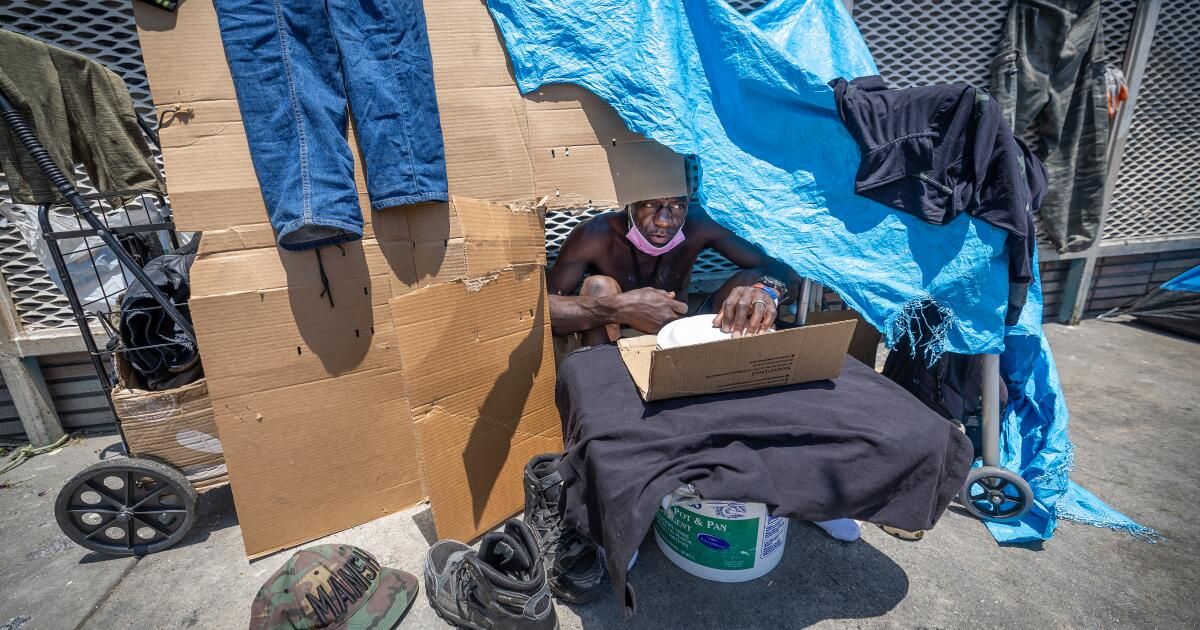

That argument is one of several at the center of a hearing in federal court in Los Angeles to determine whether the city should be held in contempt for failing to comply with an agreement, signed more than three and a half years ago, that requires it to produce more than 12,000 shelter beds or housing and remove nearly 10,000 homeless encampments from the streets.

U.S. District Court Judge David O. Carter opened the hearing in November with a thorough review of the “pattern of challenges to the city's settlement agreement and the deadlines contained therein with performance or performative compliance that only result after court hearings.”

Four days of testimony, spread over nearly two months, have produced a surprising history of confusion and disagreement over the meaning of basic terms like “homeless camp” and “people served,” leaving the impression of a city that twists definitions when it can't live up to common ones.

If a social worker tells a person on the street that a shelter bed is waiting for them, is that an “offer”? Not by the city's definition, Szabo testified Monday. An offer occurs only when someone registers at the shelter to occupy a bed.

The distinction is important because the court has required the city to “offer” shelter to anyone whose tent or makeshift shelter must be removed in pursuit of the settlement. But the city can't track how often “offers” are made, Szabo acknowledged.

“We chose to use PEH [person experiencing homelessness] “It served as our best good faith effort to meet that requirement,” he said. “It's a metric we can reasonably verify.”

“PEH cared for,” he testified, means people occupying a bed.

The city's defense is that it is doing the best it can and advancing the goals of the May 2022 agreement.

“The good news now is that the city has made extraordinary progress since then,” argued Theane Evangelis, senior counsel at the city's outside law firm. “It has served more than 8,000 people, has more than 8,000 beds online and more than 5,000 in progress. Your Honor, these numbers reflect Herculean efforts to combat homelessness, not a pattern of delay or obstruction.”

The 2020 case was brought by the LA Alliance for Human Rights, a group made up primarily of business and property owners who want cleaner streets. The lawsuit also names Los Angeles County, which reached a separate settlement in 2023. Lawyers for the group contend that the city is intentionally going dark to cover up its inadequate efforts to comply with its agreement.

“Our clients, both housed and unhoused communities, were promised more than aspirational rhetoric, Your Honor,” his attorney Elizabeth Mitchell said in her opening statement. “They were promised measurable, data-verified action, overseen by this court. Three years after the agreement, the city still fights harder against oversight than it does against homelessness.”

Two advocacy groups, LA Community Action Network and Los Angeles Catholic Worker, are intervening on behalf of homeless people in the case. Representing them, Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles attorney Shayla Myers has passionately argued that they need protection from both sides in the litigation.

There has been special focus on the city, which he suspects is using the encampment reduction plan “simply to erase visible evidence of homelessness on our streets and obscure the fact that homelessness is not improving.”

During intense questioning from Myers on Monday, Szabo struggled to defend his testimony that the city continued to maintain “largely or substantially all” of the roughly 7,000 beds it was required to produce under an earlier agreement that expired at the end of June. He clarified that he was referring to physical beds created by the city and acknowledged that more than 2,000 of those beds were leased with temporary subsidies that expire in two years.

“I don't know how many are still in use today,” he said.

The contempt hearing, a mini-trial within a trial, is the latest drama in a marathon case that has included: a 110-page order – overturned on appeal – that would have required the city to house everyone on Skid Row; an order requiring the city to provide housing to everyone living under a freeway overpass; the 7,000 beds; another agreement that requires the city to create another 12,915 beds and eliminate 9,800 encampments; a simmering battle over what a camp is: for settlement purposes it is a single tent, a vehicle, or a makeshift shelter; an order for a $3 million audit of the city's homeless programs; a hearing on whether to place those programs under a receiver; hiring a 15-member outside legal team to fight the receivership whose billings are $1.8 million and rising; the appointment of a monitor instead of a receiver; and the appeal of the appointment of said monitor, which was not even the last appeal in the case.

The current hearing largely focuses on a paragraph of the 2022 agreement that defines (in retrospect, poorly) seven progress metrics that the city must report to the court quarterly.

Three beds addresses: “the number of housing or shelter opportunities created or otherwise obtained, the number of beds or opportunities offered, and the number of beds or opportunities currently available in each Council District.”

And four, with the qualifier, “to the extent possible,” addresses people: “the number of PEHs engaged, the number of PEHs who have accepted offers of shelter or housing, the number of PEHs who have rejected offers of shelter or housing and why the offers were rejected, and the number of encampments in each Council District.”

“To the extent possible” became the cornerstone of the city's explanation for why it had used the number of occupied beds as a whole for the city's interactions with people.

Acknowledging that the city has not reported all of the required elements, Evangelis argued in his opening statement in November that the agreement “specifies that, quote, the city will work with LAHSA to include some of those elements, quote, to the extent possible. That's critical.”

The testimony that followed gave a sense of how difficult and time-consuming it would be to compile that information from the homeless database called HMIS, maintained not by the city but by the independent Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, but little evidence that the city pursued it “to the extent possible” with much zeal.

The perpetual motion nature of the procedure is straining the patience of at least one City Council member who initially supported the litigation in principle.

“The injection of investments necessitated by the case helped the city reduce homelessness for the first time after many years of increases,” Councilwoman Nithya Raman wrote in a November post on her website shortly after the contempt proceedings began.

“However, the litigation now drags on in ways that seem far removed from the goal of providing shelter and housing to people living on the streets of Los Angeles.”

Repeated hearings and data requests are “taxing an already strained system and adding significant confusion and costs,” he wrote. “In a city with limited funding and capacity, the Court's demands are now actually taking away the task of housing as many people as possible.”

One could debate who is responsible for the serial hearings. It seems certain that they will continue. Now there's a new one on the horizon after a state court judge ruled last week that the City Council illegally considered one element of the deal — the 9,800 encampment reductions — in a closed session without public input.

Citing a Times report that questioned whether the Council even voted on the encampment resolution plan, “a critical and material issue before the Court,” Carter ordered a new hearing, at a date yet to be set, to examine whether the city “deliberately and intentionally misrepresented material facts before the Court.”