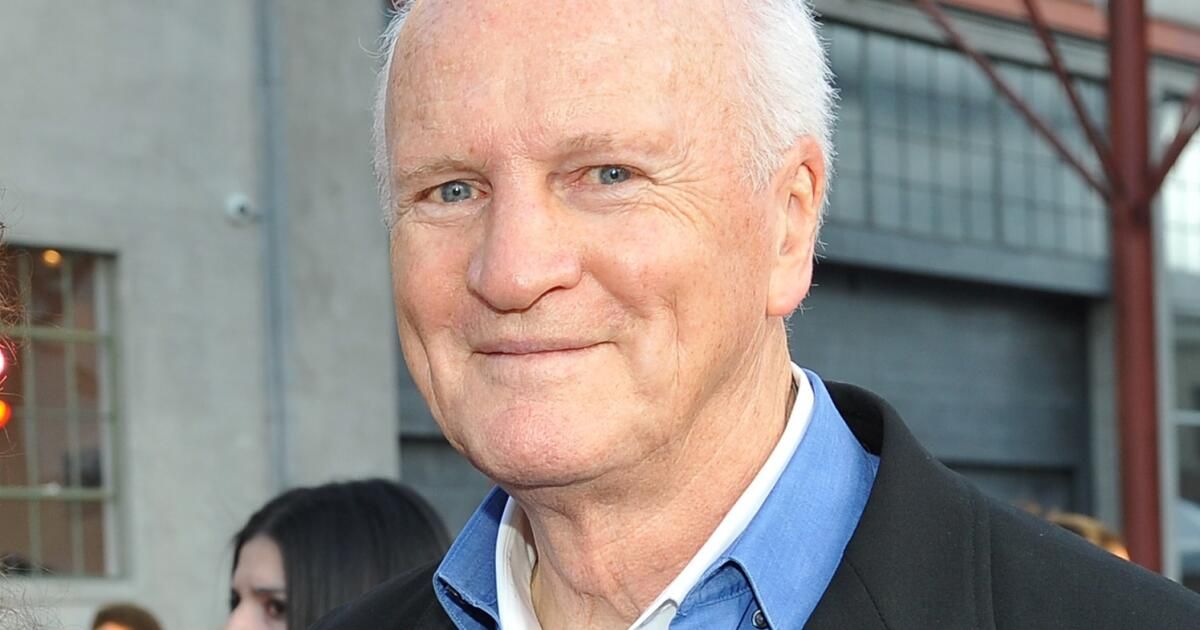

Douglas Chrismas, once known as one of the country's leading contemporary art dealers, was a man so consumed by greed and ego that he embezzled hundreds of thousands of dollars from his gallery's bankrupt assets, prosecutors said. allocate them to the rental of a museum dedicated to himself.

Chrismas, founder of Ace Gallery, had “champagne desires and caviar dreams,” Asst said. U.S. Attorney Valerie Makarewicz told a jury in an embezzlement trial she began this week in federal court. Being responsible with money, she told the jury, “didn't matter.”

But as his defense attorneys argued, Chrismas wanted to open that museum as a gift to Los Angeles and had used the money to pay rent in an effort to ultimately help the bankruptcy estate.

Who this 80-year-old man really is and what his motivations were would come down to which description the jury believed: the prosecution's or the defense's.

Megan Maitia, Chrismas' attorney, compared the interpretation of the evidence to the famous duck-rabbit illusion, an ambiguous drawing in which either animal can be seen depending on the person looking. The same evidence presented by the prosecution, Maitia said, “may mean the opposite.”

“In the end, the government will tell them and argue that they have proven all the elements of embezzlement in a bankruptcy estate,” Maitia said. “With that same evidence we are going to stand up and argue and present the case of a man who was desperate to save his business and it will be up to you to decide how you see it.”

On Friday, after less than an hour of deliberation, the jury offered its verdict on who had painted Christmas the best, finding him guilty of embezzling more than $260,000 from the bankrupt estate of Ace Gallery while acting as trustee and custodian of the estate.

When the verdict was read, those in court said Chrismas blushed and began to cry. He faces a maximum statutory sentence of 15 years in federal prison.

It was the latest downfall for the octogenarian who championed pioneering artists and sculptors such as Robert Irwin, Michael Heizer, Sol LeWitt, Bruce Nauman and Sam Francis, but who early on earned a reputation for shady dealings.

Chrismas, who opened his first gallery at age 17, has lived and operated art galleries in Los Angeles since 1969.

Legal problems and controversies have dogged him ever since, including about two dozen civil lawsuits alleging that Chrismas failed to pay artists for their work and failed to deliver artwork purchased and paid for by collectors. (Even Andy Warhol reportedly complained about missing Christmas payments.)

In 1986, Chrismas pleaded no contest to a criminal charge that he stole seven works of contemporary art worth up to $1.3 million. The stolen works included four pieces by Robert Rauschenberg and one by Warhol, one by Frank Stella and another by Donald Judd.

Chrismas and his various companies have filed for bankruptcy several times.

In 2013, Chrismas filed for bankruptcy for the last time after failing to pay rent for Ace Gallery's 30,000-square-foot flagship location on the second floor of the Wilshire Tower in Los Angeles' Miracle Mile district.

Between February 2013 and April 2016, when Ace was going through Chapter 11 proceedings, Chrismas remained the president, trustee and custodian of the gallery and oversaw all operations. This role also gave him access to the gallery's property.

Chrismas maintained control of the gallery until April 2016, when the bankruptcy court appointed an independent trustee to manage the bankruptcy estate and Chrismas was removed. Sam Leslie, a bankruptcy trustee and forensic accountant, took over management of the space and later filed a lengthy status report with the court documenting Chrismas' financial irregularities.

“The court left the defendant in charge of Ace Gallery because he and the creditors trusted him and expected him to run this business for the benefit of the people, companies and creditors of Ace Gallery,” Makarewicz told the jury. “But as the government will show you, [Chrismas] “He was not open or honest with creditors and the court.”

During the four-day trial, prosecutors told jurors that in late March and early April 2016, Chrismas embezzled approximately $264,595 belonging to the bankruptcy estate. That included a $50,000 check that Chrismas signed and that was paid to Ace Museum, an independent nonprofit corporation that Chrismas owned and controlled.

They also presented evidence that Chrismas embezzled $100,000 that a third party owed to Ace Gallery for the purchase of artwork. Those funds also went to the Ace Museum.

Ultimately, prosecutors said, Chrismas embezzled approximately $114,595 that a third party who purchased artwork owed the gallery. That money was paid to the Ace Museum's owner to keep up with its $225,000 monthly rent.

Jennifer Williams, one of Chrismas' attorneys, told jurors they did not dispute that the transactions went to the Ace Museum, but said Chrismas “understood that this was real estate.”

“There is no evidence, no evidence that Mr. Chrismas, as the owner of the gallery, could not make loans to other companies within his gallery universe,” Williams said.

By paying rent, Williams added, Chrismas also kept an option to purchase the property “live for creditors.”

Makarewicz told the jury that Chrismas had had 11 years to exercise the purchase option and “it never happened.”

The Ace Museum was intended to be his Christmas legacy, prosecutors said, “the culmination of his life's work.”

“He wanted a legacy and he was willing to use other people's money to buy that legacy,” the aide said. U.S. Attorney David Williams said during the trial. “You can't pursue your dreams with someone else's money. That's called stealing.”

The sentencing hearing is scheduled for September 9.

Times staff writer Jessica Gelt contributed to this report.