A young woman from Lincoln Heights plays the role of the Virgin. Angels visit cholos under the streetlights. A masked indigenous warrior appears before an unbelieving saint who pokes his finger in his side, much like the biblical scene of Christ after his resurrection.

These are scenes from Fabián Débora's latest paintings inspired by Renaissance artist Caravaggio in a series titled “Cara de Vago,” which will be on display at the Forest Lawn Museum until March 17.

While the Italian master depicted commoners illuminated by candlelight, Débora's work illuminates the type of people she grew up with in the Aliso Village housing projects in Boyle Heights.

“Out of darkness comes light, right?” Deborah says. “That is also in conjunction with my life and that is where spirituality lives.”

Debora, 48, found God and sobriety in 2006 after her third suicide attempt. She saw the light while running down the 5 Freeway near her mother's house while high.

“The wanderer in meditation” by the artist Fabián Débora. (Acrylic on canvas 2023-2024) in his “Cara de Vago” exhibition at the Forest Lawn Museum in Glendale on Tuesday.

(Alejandro R. Jiménez/Para De Los)

Having survived crossing the busy highway, he entered a drug rehabilitation program the next day and accepted a job answering phones at Homeboy Industries. He later became a state-certified substance abuse counselor.

Debora co-founded the Homeboy Art Academy in 2018, a trauma-focused arts center that she sees as a lifeline for young people. As a former gang member and the son of Mexican immigrants, Débora proudly explains that she found salvation after a long journey that seemed to end right where she began.

In eighth grade at Dolores Mission Catholic School in Boyle Heights, Débora threw a desk after a teacher tore up her artwork in front of her classmates. The teacher fainted and fell to the ground. Before being expelled, the director took Débora to meet a young Jesuit priest at the nearby church who often helped troubled Latino youth in the neighborhood.

Long before Father Gregory Boyle founded Homeboy Industries, he focused on helping young people with anger stemming from trauma at home and in their communities.

Standing in front of Boyle, Débora explained that no one would take away her art. That's when Boyle disarmed him with a simple request.

“He asked me to draw something for him,” says Débora. “It was the first time anyone recognized my art.”

Débora saw the assignment as a Rorschach test and planned to make a sunny drawing of a man on a beach, but then realized this was her chance to illustrate her world. She drew men with their hands behind their heads and police helicopters in the sky.

“That was when the Aliso projects emerged,” he recalls.

Débora drew in notebooks at school, at home under his mother's coffee table, and on labels in the concrete canals of the Los Angeles River and at various schools where he was expelled for fighting.

When Débora's father came to Los Angeles from El Paso, he wanted to work in construction, but ended up smuggling and selling drugs to support his family. He eventually became a drug addict and was imprisoned. Débora moved to Los Angeles when she was 5 years old and her father affectionately called him “my king.”

Without her father, Débora felt a lack of identity and was inclined to join a gang.

“It was the worst mistake of my life,” he says.

People in his neighborhood, and especially his mother, used to tell him: “You have talent. Don't tire it. There are no lesser seas.”

In 1994, Boyle intervened again. Débora faced a three-year sentence in a youth labor camp. Boyle convinced a Los Angeles Superior Court judge to place the boy in a program with East Los Streetscapers, an artist collective that began after the Chicano Moratorium in the 1970s and morphed into the Palmetto Gallery.

“Fabián was a very calm young man. He didn't brag or talk about his problems like a lot of people do,” recalls gallery co-founder Wayne Healy. “It feels good to give someone a chance to shine, and he does. “I am honored that Father Greg sent it to us.”

Debora remembers Healy being a little more direct: “He said, 'We'll take him, Father Greg. But three things, boy: Don't give me s…, don't give me s… and don't give me s…'”

Eventually, Healy asked Debora to join him and a team of artists to paint a mural in a chapel at the Central Youth Center, which struck the boy as strange because he had previously served time at the facility.

He then won an art contest with his drawing of a clown, which was displayed in Washington, D.C., near the Capitol. He was then sent to Rome to work on a mural arranged by Boyle.

At the age of 18, Débora toured the Vatican and encountered Renaissance and Baroque art for the first time. The Italian masters' depiction of dramatic gestures seemed to cut through the fabric of time.

“I was amazed,” Deborah said. “He stole my spirit.”

He didn't know it then, but that trip laid the germ of the idea that European aesthetics were brilliant, but they didn't tell their own story.

Despite her success as an artist, Débora was still a drug addict and still in a gang.

He now has the emotional maturity to acknowledge that he was hurt by the abuse his father inflicted on his family. The only community he could find was through gang life. At that time he was the father of four children. That's when he ran across the highway, but walked away with a new purpose in life.

“It wasn't until I had my third suicide attempt and a near-death experience that I recognized that there is something that we consider creator or God,” Débora said.

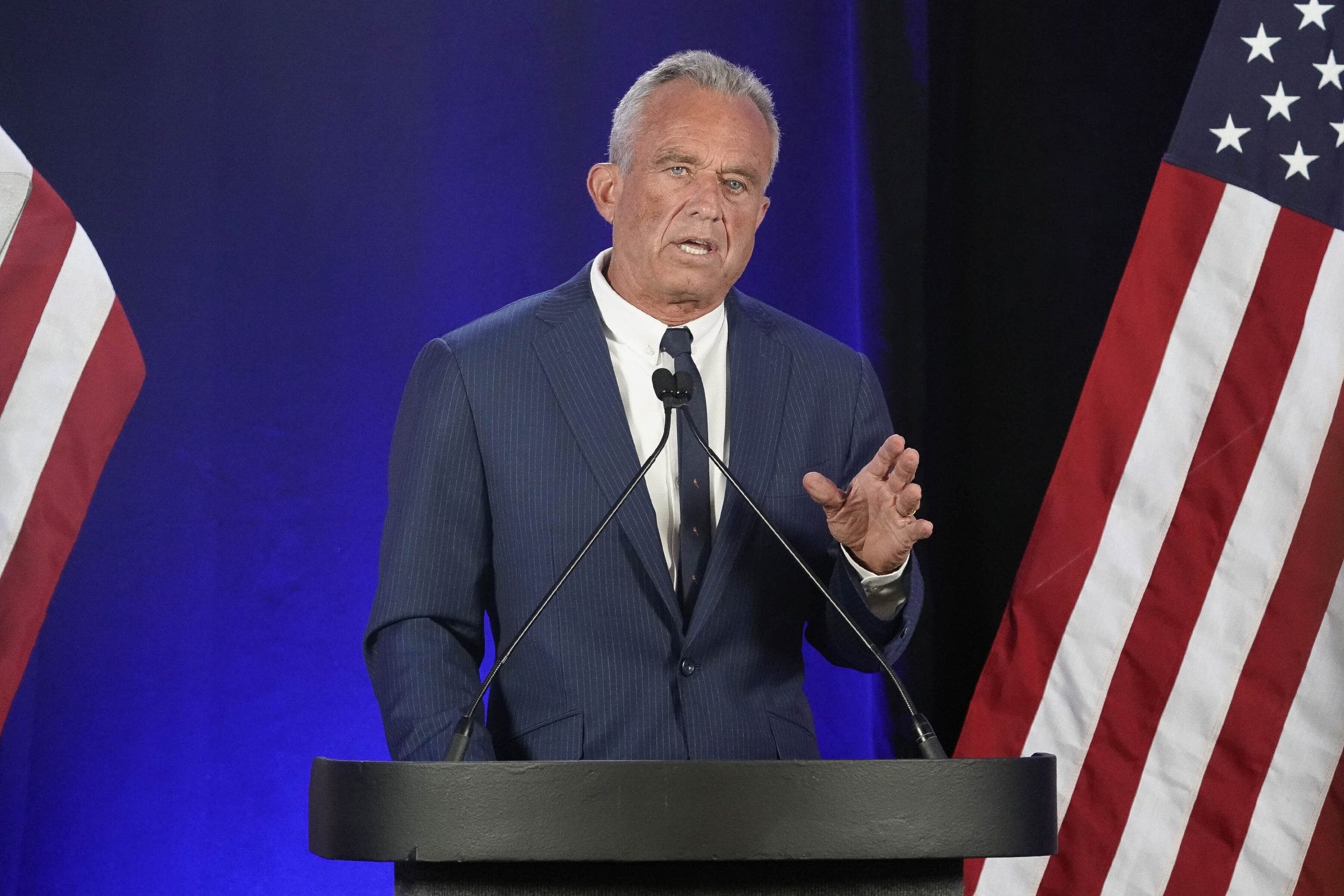

Artist Fabián Débora in his exhibition “Cara de Vago” at the Forest Lawn Museum in Glendale.

(Alejandro R. Jiménez/Para De Los)

Over the years, Débora's art went from folkloric to hyperrealism after learning color theory from artist Vincent Valdez. During the pandemic confinement, she felt the need to prove her worth by depicting scenes from her life interspersed in the style of Caravaggio.

He thought that high-end galleries and museums would have to pay attention to his work if it referenced the Renaissance.

“By using the art form of Baroque and Renaissance style, then I can get your attention. And now that I have your attention, let’s start the conversation,” Débora said.

“I think what's really important is that he's not copying these masters, but working alongside them,” said associate professor of art history Hector Reyes at USC. “Fabián is very good at taking street strategies and his own familiarity with street life and translating them into a kind of rhetorical device that really grabs your attention and draws you in.”

Art curator Vida Patricia Rodríguez finds Débora's reverence and faith for people considered marginalized endearing and part of the reason her art resonates with both Latinos and non-Latinos.

“He has a very strong commitment to restoring humanity within the people of his community and the subculture in which he grew up,” Rodriguez said.

On a recent afternoon at the academy in East Los Angeles, Débora is surrounded by young people exploring their creative limits. They see him as an old man who hit rock bottom, but found success again.

Artist Fabián Débora, left, with curator Vida Patricia Rodríguez with “Incarceration to Artistic Resurrection” behind them at their “Cara de Vago” exhibit at the Forest Lawn Museum in Glendale.

(Alejandro R. Jiménez/Para De Los)

Savannah Gonzalez, 19, of Lincoln Heights, posed as Madonna for Débora's painting “Madonna of the Rosary.” González can relate to Débora's story about growing up in a neighborhood with gang violence and substance abuse.

At the opening of the “Cara de Vago” gallery earlier this month, González acknowledged that the exhibit on the Forest Lawn funeral grounds was not far from where his friend Joseph Bustillo Reyes was buried.

“He was killed by gang violence and it wasn't fair. He was 16 years old and I just lost him,” says González. “But he was very close to us at the exhibition. He felt like he was there with us.”

She feels that Débora and the academy helped her realize the power of art.

“It broadened my horizons of what I can do in so many ways,” he says.

Also visiting the academy that day is Débora's son, Fabián Debora Jr. In a back room, Débora carried a pair of young eagle feathers and a bowl of burning sage to cleanse her son.

The 24-year-old isn't as lost as his father was at that age, but he's still getting into trouble, Debora said. During the cleaning, Deborah repeats several prayers while she hits her son with the feathers. She says that whatever she did when she was young should not come back to haunt her son.

Deborah tells her son with a quiet desperation in her voice, “I love you and I want you to come home.”

His son responds, “I love you, Dad.”