As the Eaton and Palisades fires quickly jumped between tightly packed homes, the proactive steps some residents took to retrofit their homes with fire-resistant building materials and clear flammable brush became an important indicator of a home's fate.

Early adopters who cleared vegetation and flammable materials within the first five feet of their homes' walls, according to draft rules for the state's much-debated “ground zero” regulations, fared better than those who did not, found on-the-ground research from the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety released Wednesday.

For a week in January, while the fires were still burning, the insurance team inspected more than 250 damaged, destroyed and uninjured homes in Altadena and Pacific Palisades.

On properties where most of the ground zero land was covered with vegetation and flammable materials, fires destroyed 27% of the homes; On properties with less than a quarter of ground zero covered, only 9% was destroyed.

The Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, an independent nonprofit research organization funded by the insurance industry, conducted similar research for the Waldo Canyon Fire in Colorado in 2012, the Lahaina Fire in Hawaii in 2023, and the Tubbs, Camp and Woolsey Fires in California in 2017 and 2018.

While a handful of recent studies have found that houses with sparse vegetation at ground zero were more likely to survive fires, skeptics say that still falls short of a scientific consensus.

Travis Longcore, senior associate director and adjunct professor at the UCLA Institute for Environment and Sustainability, cautioned that the insurance nonprofit's results are only exploratory: The team did not analyze whether other factors, such as the age of the homes, were influencing its analysis of ground zero, and how the nonprofit characterizes ground zero for its report, he noted, does not accurately reflect California's draft regulations.

Meanwhile, Michael Gollner, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley who studies how wildfires destroy and damage homes, noted that the nonprofit's sample does not perfectly represent all burned areas, as the group specifically focused on damaged properties and was limited by active shooting.

Still, the nonprofit's findings help tie together growing evidence of ground zero's effectiveness from laboratory testing (aimed at identifying pathways fire can use to enter a home) with real-world analyzes of what measures protected homes in wildfires, Gollner said.

TO Gollner's recent study Examining more than 47,000 structures in five large California fires (which did not include the Eaton and Palisades fires) found that of properties that cleared ground zero vegetation, 37% survived, compared to 20% that did not.

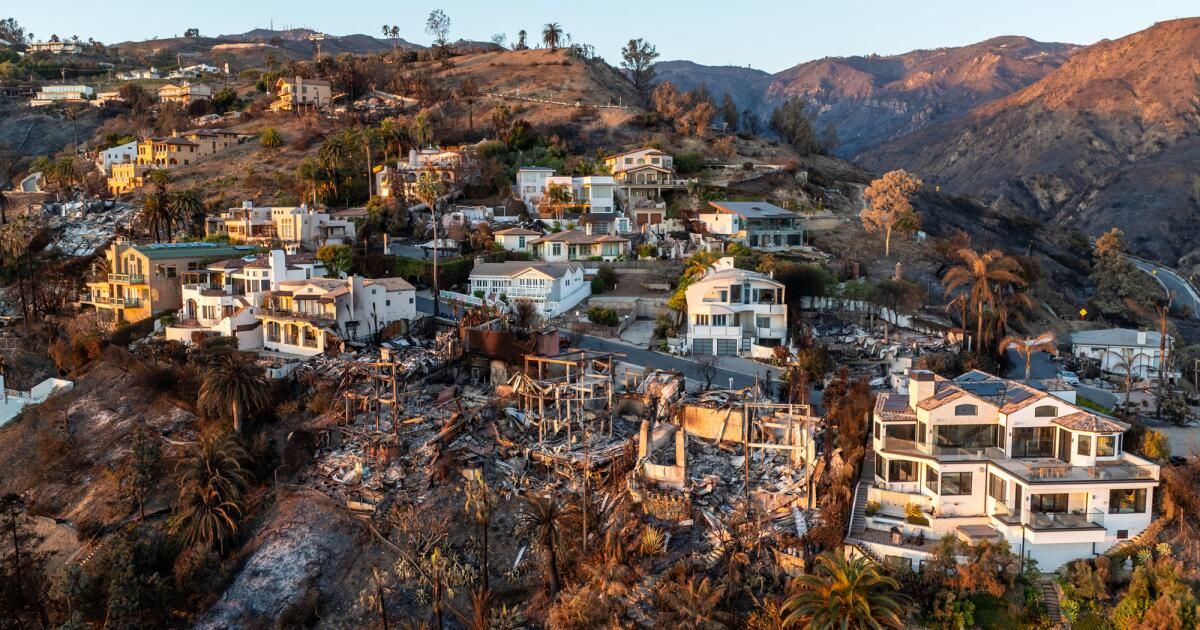

Once a fire spreads from wildland to an urban area, homes become the primary fuel source. When a house catches fire, it increases the chance that nearby houses will also burn down. This is especially true when houses are very crowded.

Looking at data from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection for the entirety of the two fires, the insurance team found that “hardened” homes in Altadena and Palisades that had noncombustible roofs, fire-resistant siding, double-pane windows, and enclosed eaves survived without damage at least 66% of the time, if they were at least 20 feet away from other structures.

But when the distance was less than 10 feet, only 45% of the hardened houses escaped undamaged.

“Structure spacing is the most definitive way to differentiate what survives and what doesn't,” said Roy Wright, president and CEO of the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Security. At the same time, Wright said, “it's not feasible to change that.”

In analyzing the measures residents are most likely to take, the insurance nonprofit found that the best approach is for homeowners to implement as many home hardening and defensible space measures as they can. Each of them can reduce a home's fire risk by a few percentage points, and when combined, the effect can be significant.

Looking at ground zero, the insurance team found a number of examples of how vegetation and flammable materials near a home could aid in the destruction of a property.

At one house, embers appeared to have ignited some hedges a few meters from the structure. That heat was enough to shatter a single-pane window, creating the perfect opportunity for embers to enter and burn the house from the inside out. He miraculously survived.

In others, embers from fires fell into garbage and recycling bins near homes, sometimes poking holes in the plastic lids and igniting the material inside. In one case, the fire in the container spread to a nearby garage door, but the house was saved.

Wooden decks and fences were also common accomplices that helped embers ignite a structure.

California's current draft ground zero regulations take into account some of those risks. They prohibit wooden fences within the first five feet of a house; The state's ground zero committee is also considering banning virtually all vegetation in the zone or simply limiting it (good trees are allowed, anyway).

On the other hand, the draft regulations do not prohibit maintaining trash containers in the area, which the committee determined would be difficult to enforce. They also do not require homeowners to replace wood decking.

The controversy surrounding the draft regulations centers on the proposal to remove virtually all healthy vegetation, including shrubs and grasses, from the area.

Critics argue that, given the financial burden that ground zero would impose on homeowners, the state should focus on measures with lower costs and significant proven benefit.

“Focusing on vegetation is a mistake,” said David Lefkowith, president of the Mandeville Canyon Association.

At its most recent ground zero meeting, the Board of Forestry and Fire Protection directed staff to further investigate the affordability of the draft regulations.

“As the Board and subcommittee consider which set of options best balance safety, urgency and public feasibility, we are also shifting our focus to implementation and looking to state leaders to identify resources to comply with this first-in-the-nation regulation,” Tony Andersen, the board's executive director, said in a statement. “The need is urgent, but we also want to invest the time necessary to do it right.”

Housing consolidation and defensible space are just two of the many strategies used to protect lives and property. The insurance team suspects that many of the close calls they studied in the field (houses that nearly burned down but didn't burn down) ultimately survived thanks to the intervention of firefighters. Wildfire experts also recommend programs to prevent ignitions in the first place and manage wildland areas to prevent the intense spread of a fire that ignites.

For Wright, the report is a reminder of the importance of community. The fate of any individual home is tied to those nearby: it takes an entire neighborhood reinforcing its homes and maintaining its lawns to achieve herd immunity against the contagious spread of fire.

“When there is collective action, the results change,” Wright said. “Forest fires are insidious. They don't stop at the fence.”