WASHINGTON- RV had already spent six months detained in a facility in California when he won his immigration court case in June.

He stated that he had fled his native Cuba in 2024 after protesting against the government, for which he was imprisoned, surveilled and persecuted. So after being kidnapped in Mexico, he entered the United States illegally and told border agents he feared for his life.

An immigration court judge granted him protection from deportation to Cuba, and RV, 21, hoped to join his family in Florida.

But RV, who asked that his full name not be used for fear of government retaliation, has not been revealed. At the detention center, he said, agents have told him they will still find a way to deport him, if not to Cuba, then perhaps to Panama or Costa Rica.

“The wait is very hard,” he said in an interview. “It's like they don't want to accept that I won.”

RV is among what immigration attorneys describe as a growing trend: Some immigrants who gain protection from deportation to their home countries are being detained indefinitely.

Often, the person has been detained while the federal government appealed its victory or searched for another country willing to take them.

The government has long had the ability to make these types of appeals or to find another country where it can deport someone; the Department of Homeland Security generally has 90 days find another place to send them.

But in practice, such expulsions to third countries were rare, so the person was usually released and allowed to remain in the US.

That practice has changed under the Trump administration. Recent instructions to Immigration and Customs Enforcement staff favor keeping people in detention. A June 24 memorandumFor example, it states that “local offices no longer have the option of releasing foreigners at their discretion.”

At stake are cases involving immigrants who, instead of being granted asylum, are granted one of two types of immigration relief, known as “withholding of removal” orders and protection under the International Convention Against Torture. Both have higher burdens of proof than asylum, but do not provide a path to citizenship.

These forms of relief differ from asylum in one key respect: while asylum protects against deportation to any location, the others only protect against deportation to a country where the person is at risk of harm or torture.

Jennifer Norris, an attorney with the Immigrant Defenders Law Center, said the government's actions now effectively make the suspension of deportation and protection under the convention against torture meaningless.

“We have entered a dangerous era,” Norris said. “These are clients who did everything right. They won their cases before an immigration judge and are now treated like criminals and remain detained even after an immigration judge rules in their favor.”

Laura Lunn, director of advocacy and litigation at the Rocky Mountain Immigrant Defense Network in Colorado, noted that rules against double jeopardy do not apply in these cases, so the government has the ability to appeal when it loses.

“Here they have a lot of control over whether someone stays in detention because if they just file an appeal, that person can stay in detention for at least six months or what could be years,” Lunn said.

Homeland Security did not respond to specific questions and declined to comment.

Lawyers who represent immigrants in prolonged detention say the government is keeping people locked up in hopes of wearing their clients down into giving up their fight to remain in the United States.

Ngựa, a Vietnamese man who asked to be identified by his family nickname, which means horse, has been detained in California since he illegally crossed the southern border in March.

Ngựa fled Vietnam last year after being tortured by police officers who tried to extort him for a “protection tax,” according to his asylum application. When he refused, the officers beat him, imprisoned him, and threatened to kill him and his family.

An immigration judge recently denied Ngựa asylum but granted him protection under the convention against torture. His pro bono lawyers have appealed the asylum denial.

In an interview through an interpreter, he said he chose to seek safety in the United States because he believed the government of any other country would deport him back to Vietnam. He said he did not anticipate that U.S. officials would try to get rid of him.

Ngựa said ICE officials told him they know they can't send him back to Vietnam, but they will find another country willing to take him. Every morning, he said, an officer goes from dorm to dorm asking if anyone wants to self-deport.

The thought of being expelled keeps him awake at night, but the alternative is almost as bad: “I'm afraid they'll keep me here for years,” he said.

DHS regulations allow continued detention when “there is a significant probability of removing a detained alien in the reasonably foreseeable future.”

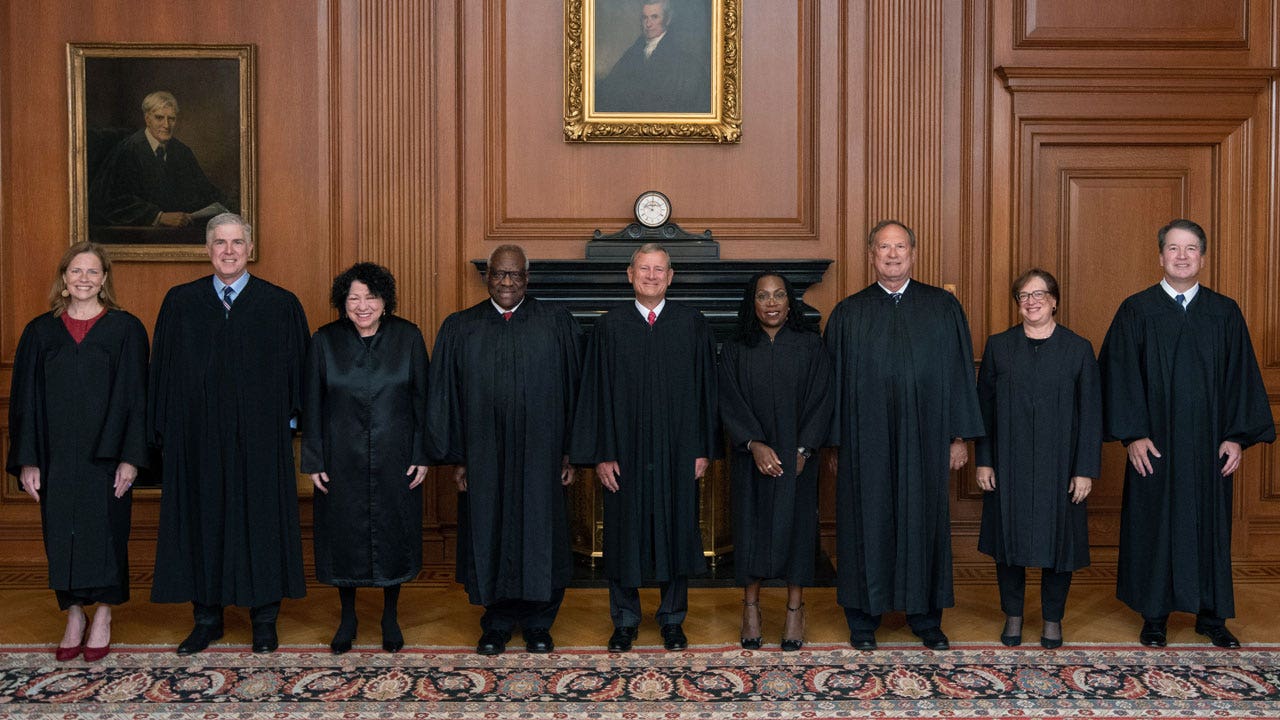

Such scenarios are increasingly possible since a Supreme Court ruling in June expanded immigration authorities' ability to quickly deport people to countries where they have no personal connection.

After the ruling, ICE published guide order agents to generally give migrants whose expulsion to a third country “at least 24 hours’ notice,” but only six hours in “urgent circumstances.”

The guidance also says the United States needs to receive credible diplomatic assurances that deported people will not be persecuted or tortured.

This year, the Trump administration has negotiated deals with several countries, including Ghana, El Salvador and South Sudan, which is on the brink of civil war, to accept deportees.

“It has become more common practice for the government to retain people who obtain protection because they are actively seeking, in most cases, to be accepted by a third country,” said Trina Realmuto, executive director of the National Immigration Litigation Alliance.

Realmuto is one of the lead attorneys in the case challenging the Department of Homeland Security's third-country removal practice.

Federal law states that Homeland Security must first look for alternative countries to which the person being deported has some personal connection and then, if that is “impracticable, inadvisable, or impossible,” find a country whose government is willing to accept them.

Realmuto said the Trump administration is moving directly to that last resort. As a result, he said, several people who were deported to a third country have been sent by officials back to the country they originally fled.

Among them is Rabbiatu Kuyateh, a 58-year-old woman who fled Sierra Leone's civil war 30 years ago and settled in Maryland until ICE agents detained her this summer during their annual check-in.

NBC News reported that because a judge had prohibited ICE from sending her back to Sierra Leone, where she had been tortured, the agency deported her to Ghana. But Ghanaian officials forcibly put her on a bus bound for Sierra Leone.

In fiscal year 2024, 2,506 people were granted withholding of removal or protection under the torture convention, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Realmuto said that, like Kuyateh, tens of thousands of immigrants have been granted detention or deferment relief over several decades. Those people could now risk being detained again while the government works to expel them to another country, he said.

The case of FB, a 27-year-old Colombian woman who entered the United States through the San Ysidro port of entry in 2024, further illustrates the government's approach to the anti-torture convention. FB asked to be identified by her initials for fear of retaliation from the US government.

In February, FB gained protection under the convention against torture. But instead of releasing her, Homeland Security said it was trying to expel her to Honduras, Guatemala or Brazil.

In September, FB's lawyers filed a petition in federal court seeking his release.

“It's a little difficult to argue that someone's removal is imminent when they've been detained for eight months,” said his attorney, Kristen Coffey.

Court records show that the judge initially denied the request after ICE officials claimed they had booked him on a flight to Bolivia that would depart three days later.

But a month later, he was still in US custody.

In an order granting FB's release last month, U.S. District Court Judge Tanya Walton Pratt in Indiana said the government's claim that FB would be imminently deported had “proven false” and that holding her in detention was “contrary to the Constitution and laws of the United States.”

She was released the same day.