There was probably no Dodgers fan more grateful to see the Blue Crew lose badly in the opening game of the World Series than Conrado Contreras. Look, the 75-year-old was happy to enjoy himself. any Fall classic at all.

One year ago tomorrow, the Zacatecas native suffered a heart attack and a minor stroke in the moments after watching his Dodgers win Game 2 of the World Series against the New York Yankees. He spent three days in an induced coma at St. Francis Medical Center in Lynwood and regained consciousness upon news from jubilant nurses that the Dodgers had won the championship.

The lifelong baseball fan had no idea what they were talking about. His passion for the sport was lost along with his memory.

When family members presented highlights from the 2024 championship during his rehab at a clinic in Gardena throughout the end of the year, the former carpenter would shrug his shoulders and change the channel. When someone told him that legendary Dodgers pitcher Fernando Valenzuela had died, Contreras swore he had just seen his fellow Mexican pitch in the ballpark.

It wasn't until the 2025 baseball season rolled around that Contreras' mind began to truly recover. He watched games from his old home in unincorporated Florence-Graham and learned to love the Dodgers again. But he no longer applauded like before. Contreras followed doctor's orders to remain calm when the Dodgers were losing instead of cursing as in the past and silently applauding when the team won when he would have previously roared.

He is my sister Alejandrina's father-in-law. And I wanted to hang out with Don Conrado at Game 1 of this year's World Series to experience fandom in all its mortality.

Wearing a flat-brimmed hat and a blue 2024 World Series champion Dodgers jersey, I caught Contreras just as he entered my sister's house in Norwalk, holding on to his walker with the help of Alejandrina's husband, Conrad. His father speaks slower than before and can no longer drive, but Contreras is once again the same man his family knows: witty, observant, and crazy about baseball.

A schoolyard pitcher in his hometown of Mount EscobedoContreras joined the Dodgers almost as soon as he emigrated to the United States in 1970 to join a brother in Highland Park. I used to attend games every week “when $10 got two people into the stadium and you could also have a hot dog,” Contreras told me in Spanish before Game 1 began.

His stories from those years were immaculate. Don Sutton pitching a shutout. The Cincinnati Reds always “willing to play to the death.” Pittsburgh Pirates slugger Willie Stargell hit a home run at Dodger Stadium in 1973 “and we were all looking over our heads in awe.”

Contreras was such a fan that he took his pregnant wife, Mary, to see Valenzuela pitch on the day in 1983 that Conrad was supposed to attend because they were handing out T-shirts that said “Yo (Corazón) Fernando,” an anecdote that left his son stunned.

“What happened to the shirt?” Conrad asked his mother in Spanish.

“I threw it in the trash,” Mary, 61, responded.

“Now they would cost a lot of money!” he groaned.

“They were cheap! The color really faded quickly.”

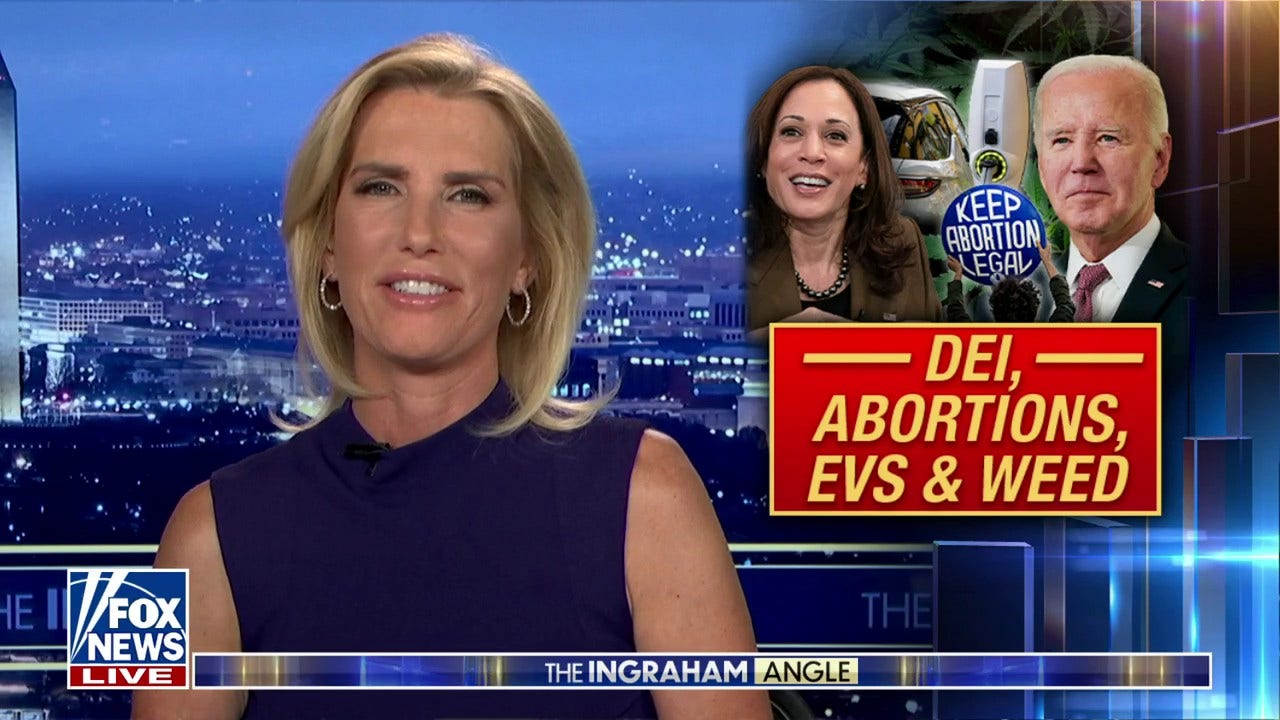

Los Angeles Dodgers two-way player Shohei Ohtani hits a two-run home run during the seventh inning of Game 1 of the World Series between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Toronto Blue Jays at the Roger Center on Friday in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The Blue Jays won 11-4.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

The family continued to attend games throughout Conrad's teenage years, but stopped attending “when not even the birds could afford to attend,” Mary said. Conrad, 42, believes the last time he went to a game with his father was “at least” 20 years ago. But they regularly watched the games on television. It was he who administered CPR a year ago that saved his father's life.

“I was walking around the house angry during that whole game,” Conrad said.

“No, well, Roberto was making me mad,” replied Conrado, his nickname for Dodgers manager Dave Roberts. “But I can't get angry anymore.”

I asked him what he thought this year's series would be like. He mentioned Shohei Ohtani, who he kept calling. the japanese in a respectful tone because, well, your memory may be fuzzy.

“He strikes out too much, but when he strikes out, he strikes out. If he plays like that, they win the series. But if Toronto does it, forget it.”

One more question before the game, the one that many liberal Latino Dodger fans are sick to their stomachs right now: Is it ethical to support the team considering that they haven't been very vocal in opposing Donald Trump's deportation campaign and that owner Mark Walter has investments in companies that are profiting from it?

“Sports should not get involved in politics, but all sports owners are with Trumpets” he said, using a nickname I’ve heard more than a few rancher libertarians use for Trump.

“Then what is to be done? They remained the migration outside the stadium,” referring to a failed June attempt by federal agents to enter the stadium parking lot. “If the team had allowed that, then there would be a big problem.”

Mary was not so understanding. “Latinos shouldn't let the Dodgers go so easily. But when Latinos give up, they give up.”

It was game time.

Conrad donned a gray Dodger away jersey to match the team's black cap. My sister, a Los Angeles fan for some reason, was wearing a Kiké Hernández t-shirt “because she supports immigrants.”

“The only good thing about the Dodgers is that they're not winning with a gringo,” said Mary, who doesn't really care much about baseball because she finds it boring. “It's someone [Ohtani] “Whoever doesn't want to speak English, who earns it.”

Her husband smiled.

“Let's see if Mary likes baseball.”

“That will be the real “miracle,” he responded sharply.

Contreras rubbed his hands with joy when the Dodgers took a 2-0 lead in the top of the third and simply frowned when the Blue Jays tied it in the bottom of the fourth while we enjoyed takeout from Taco Nazo. “His anger comes in waves, it's a journey,” Conrad said. “He is calmer but gets angry“

“WHO?” Conrado remained impassive.

When Dodgers starting pitcher Blake Snell left the game with the bases loaded and no one out in the bottom of the sixth, Contreras shook his head in disgust but kept his voice calm.

“This is what makes me angry. They should have eliminated it a long time ago, but Roberto didn't. This is what I was afraid of. When Toronto advances, they advance. They won't stop until they destroy.”

Sure enough, the Blue Jays erupted for nine runs in that inning, including a two-run explosion by catcher Alejandro Kirk, who had sparked the Blue Jays' initial rally a few innings earlier.

At the beginning of the game, Alejandrina had told Conrado that Kirk was a native of Tijuana. Pride in shared roots, though generations apart, took some of the sting out of his home run, which made the score a humiliating 11-2.

“Thank God he's Mexican,” Conrado told his son, patting him on the knee. “That's what we have left” to be happy with the game.

One inning later, Contreras began to feel dizzy. His sugar level was high. Mary took off her jacket to fix her insulin device. Penny, my sister's corgi, jumped onto the couch and lay on her lap.

“They know when someone is sick, right?” He didn't tell anyone before scratching Penny's belly and cooing, “You know I'm sick, right? I'm sick!”

When the “massacre” finally ended, Contreras remained philosophical.

“It's amazing that I can see this. But I'm still bad. My feet hurt, my memory isn't what it used to be, my sense of balance isn't there. But there are the Dodgers. But they need to win.”

Conrad went to the bedroom to get his father's walker.

“Do you want a Toronto jersey now?” he joked.

His father looked at him in silence. “No, that would give me another heart attack.”