I remember it well: his toothy smile. Her spiky haircut. Her high cheekbones and her loud laugh.

I also remember how I called the teenager. Queer. Fairy. Even worse names.

We attended Anaheim High in the mid-1990s. I was a senior, he was a freshman. He was one of the few students on an overwhelmingly Latino campus. He endured ridicule, epithets, and bullying, while attacking his antagonists with withering insults more often than not.

That didn't stop me or the others.

I learned my homophobia from sexist cousins and from a father who was so anti-gay that when my partner came to our house for my sister's party, my dad forbade us from going to the pool, so he wouldn't infect us with something. Homosexuality, I thought, was not just an abomination. “They” were a threat to the people I loved (Americans, Mexicans, Catholics, good people) by simply existing.

When my best friend, Art, told me to rein in my prejudices, I would blurt out a litany of Bible verses: Leviticus this, Genesis that, lots of Paul. Nothing could convince me that I should stop being unpleasant, much less accept gays and lesbians as normal.

An HBO movie changed everything. In Mr. Elder's biology class, we watched “And the Band Played On,” based on Randy Shilts' best-selling book about the early days of AIDS. I turned away in disgust at any hint of same-sex affection. But the story – about how the Reagan administration and society at large allowed a terrible disease to spread because it first emerged in the gay community – haunted me.

I might have thought homosexuality was terrible, but an indifferent government that let people die for who they were was much worse. A few months later, I approached my classmate and apologized. I was honest, but I'll never forget the understandable skepticism on his face.

I've been trying to atone for my sins ever since.

I told my brother when he entered fourth grade to tell me about the time he and his friends played a schoolyard game called Smear the Queer. One person got the tag at random and everyone else threw a soccer ball at him. I knew it wasn't a matter of Yeah my brother would join but when – because they taught me that game too.

One day, he came home excited and said that he and his friends finally played Smear the Queer. I explained to him what the word meant and what the game represented, and made him swear that he would never join again.

Professionally, I have continued to criticize politicians and groups who attempt to deny LGBTQ+ people their rights and dignity. Today, I have close LGBTQ+ friends and still engage in heated debates with loved ones about their latent and overt homophobia.

But I am an imperfect ally. I can't erase the pain I inflicted before, so I remember those dark days to remind myself that I can always do better.

That's why a recent poll conducted for The Times by NORC at the University of Chicago and paid for by the California Endowment brought me some hope about this country's long, painful journey toward acceptance of LGBTQ+ people, and was also proof of How much work is there. it is still to be done.

Christians hold signs as they gathered to pray and protest the Dodgers' inclusion of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence in their Pride Night program at Dodger Stadium in 2023.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

The survey was a sequel of sorts to a pioneering 1985 Times project that asked people how they felt about homosexuality. The differences between then and now are stark. Back then, 73% felt that relationships between gays and lesbians were wrong, which according to an accompanying Times article was virtually unchanged from a similar Gallup poll in 1973. This most recent poll? Only 28% felt this way.

In 1985, 51% of respondents thought there should be workplace protections for gays and lesbians. Today, the figure is 77%. The previous survey showed that 35% felt “uncomfortable with homosexuals.” This time the question wasn't even asked.

The 1985 Times study was published without photographs or comments. This time, we published our findings with moving essays from my current and former LGBTQ+ colleagues. The survey and essays were part of a project called “Our Strangest Century” that is available on our website and will appear in print as a special section on June 23.

These surveys show that beliefs change over time and exposure. But while there is greater acceptance of gays and lesbians today, a new intolerance has emerged. The 1985 survey did not ask about transgender people. The Times/NORC poll demonstrated this, and the results are discouraging.

More than a third said they would be very or somewhat upset if their child came out as gay or lesbian (in 1985, the figure was 89%). But if the child declared themselves trans or non-binary, the percentage increased to 48%. When it came to letting people “[live] their lives as they want”, only 19% disapproved “strongly or somewhat” if the person was gay or lesbian. Trans or non-binary? 31%.

Even more revealing was the question of whether more attention to trans and non-binary people in media and politics was good or bad. Only 16% thought it was good, while 40% thought it was bad (42% answered “none”).

Unsurprisingly, the survey shows that politics and religion correlate with people's opinions on LGBTQ+ issues. But I also think that lack of familiarity plays a huge role. While 72% of American adults in the Times/NORC poll said they knew someone who identified as gay or lesbian, only 27% said the same about transgender or nonbinary people. When you have a Jesus moment with someone you have been taught to see as “different,” you quickly realize what a fool you are.

Case in point: me, again.

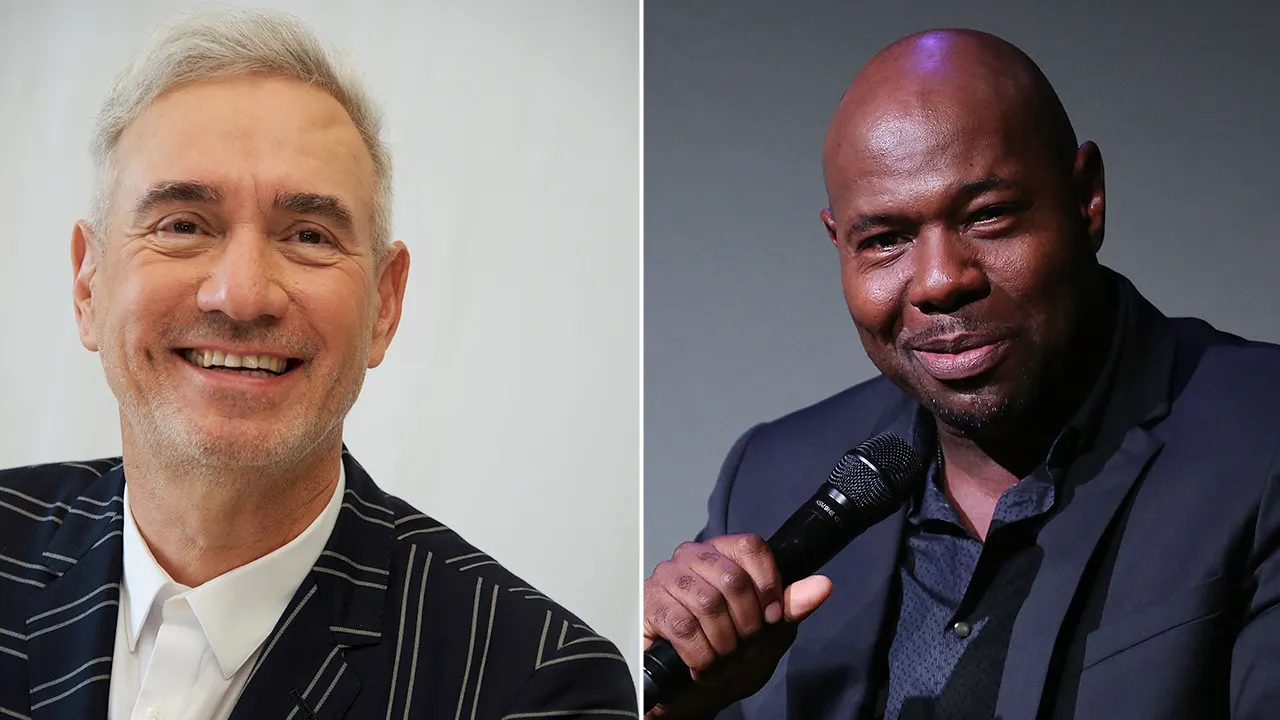

A decade after my disgraceful behavior toward my Anaheim High classmate, I read a powerful column by Times sportswriter Mike Penner revealing that I would return from vacation as Christine Daniels.

“I am a transgender sportswriter,” Penner wrote. “It took me more than 40 years, a million tears, and hundreds of hours of heartbreaking therapy to gather the courage to write those words.”

I was so touched that I sent a thank you note through a mutual friend. To my surprise and delight, Daniels wanted to meet with me to talk about how to deal with sudden fame. Then he was at OC Weekly and The Times had introduced me and my column “Ask a Mexican!”, which caused an avalanche of attention.

I was nervous, and not just about meeting a writer whose work I had long admired. I didn't know anyone who identified as transgender, and I was worried about offending Daniels by asking an inappropriate question or using the wrong name or pronoun.

Allied Universal security guards Gregory Winfrey, left, and Benedicto Barnachea raise a Pride flag over the Kenneth Hahn Administration Hall in downtown Los Angeles in 2023.

(Gary Coronado/Los Angeles Times)

At a panini joint in Old Towne Orange, Daniels quickly disabused me of my low-key transphobia. I found myself focusing on the person in front of me: kind. Funny. Bright. Happy. At the Weekly I continued to proudly attack the demons who ridiculed Daniels, until the sad day in 2009 when Mike Penner, who had used that byline again in The Times, committed suicide.

Today, as city councils reject calls to fly rainbow flags during Pride Month and school boards ban books and lesson plans that touch on any LGBTQ+ topics, as adults protest story times in the name of protecting children and they hurl invectives at the drag nuns while mocking the promotion. from “Latinx”, I remember my journey from hatred to humility.

I asked Bamby Salcedo, president and CEO of the TransLatin@ Coalition, about the best way to change closed minds and hearts.

It's not about “doing training or checking a DEI box,” he said, referring to diversity, equity and inclusion; it's about having difficult conversations from a place of love, “because hate doesn't win.”

A sincere rejection of someone’s anti-LGBTQ+ attitudes, Salcedo said, can “put out that seed of change. And if you plant it, harvest sale [the harvest comes].”

I remind myself that people can change, and those who have experienced the road to Damascus moment should urge others to follow our path.

After all, the most avoidable sin is ignorance, and all sinners must repent. Take it from one.