In the land of killer rides, Salud Garcia's ride is so difficult he should get a gold medal at the finish line every day.

He leaves his home in Reseda before dawn, takes a bus to a train, then another bus, followed by another. When she arrives at her workplace near LAX, more than two hours later, it's around 7 am.

“I run to the bathroom and then I get to work,” said García, a dishwasher for a catering company that serves airlines.

After work, Garcia sometimes gets lucky and a co-worker gives him a ride home. But usually she makes the trip in reverse, which means eight or nine hours at work, then several hours in transit.

California is about to be hit by a wave of aging populations, and Steve Lopez is taking advantage of it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of old age and how some people are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

What makes this even more notable, or heartbreaking, if you prefer, is his age.

“I'll be 81 in August,” said Garcia, who is known for leading her colleagues in Inglewood on a picket line during their lunch break in their fight for a better contract. She told me that she won't benefit much, given her age, but she wants younger employees to be able to “retire with dignity.”

I heard about Garcia from a Unite Here Local 11 spokeswoman while researching a column about workers who can't retire. I have met many people who continue working because they want to, but I wanted to meet people who continue working because they have to.

The rent is too high. The retirement fund has been depleted or never existed. Social Security doesn't cover the bills and the children and grandchildren need help. People continue to work, often in physically demanding jobs, for all of those reasons and more.

Last summer I visited a early morning pickets, At another United Here site, outside the Viceroy Hotel in Santa Monica, among the 23 housekeepers, dishwashers and other employees who asked for a better contract, six of them were in their 60s and two were in their 70s.

“My knee hurts,” said José Ayala, a 67-year-old dishwasher, who told me he worked two jobs, for a total of 13 hours each day, to support a family of four in a Culver City apartment.

A few years ago, I was researching my book on retirement and will never forget the sight of a man in his 70s working in a big box store near Knott's Berry Farm. He was somewhat disfigured by a cancer operation and he told me that his foot hurt because he spent so many hours on his feet every day guarding the self-checkout counters.

He had retired once, but had to return to work when funds dwindled and costs increased, and he didn't know when he might be in a good financial position to retire again. When I spoke to his wife about a year later, she told me that her husband had finally retired and then died a short time later.

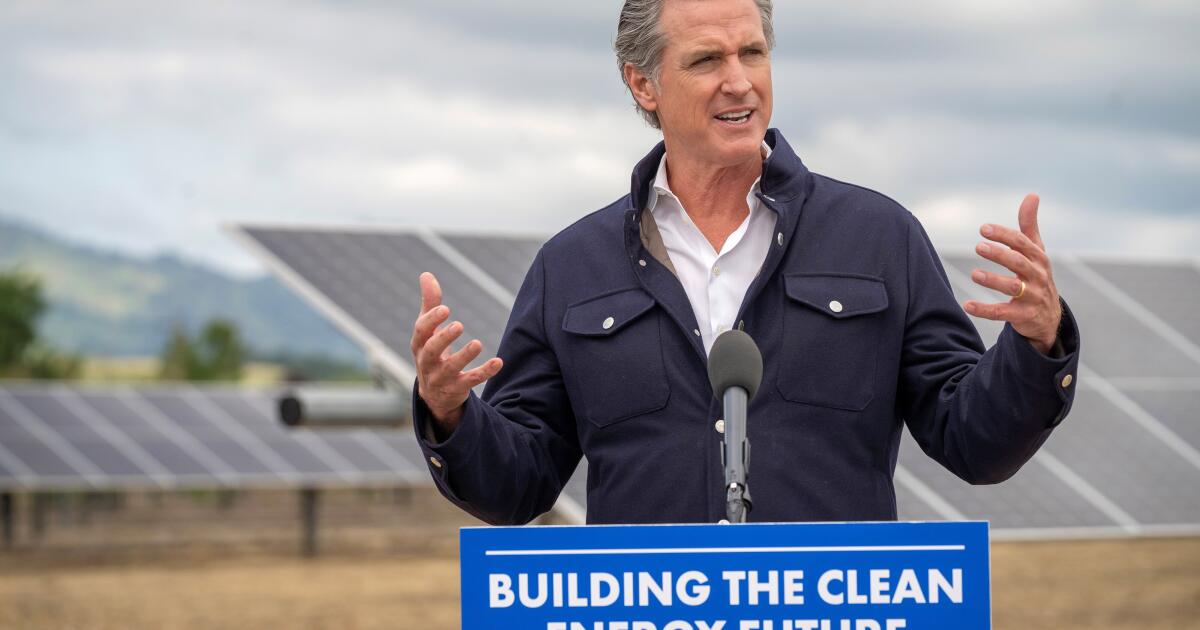

Salud García, 80, on the right, takes a break after walking on the picket line. Experts say there has been an increase in the number of working people between the ages of 65 and 70.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“There has been an increase in the number of people working over the age of 65 and even over the age of 70,” said Nari Rhee, director of the Retirement Security Program at the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

But finding work isn't easy, she said, thanks in part to age discrimination, especially in technology.

Since pensions have virtually disappeared in the private sector, Rhee said, half of American workers have no retirement benefits other than Social Security. Even if an employer offers 401(k) plans, “most lower-wage workers don't choose to participate because they can't afford it. … The system has really let down American workers, especially at the lower end of the labor market.”

Garcia, who has been at his current job for more than 30 years, earns a little more than $21 an hour with a health care plan and a 401(k), among other benefits under the terms of a contract. But he expired almost two years ago and negotiations are behind schedule.

His employer, an airline caterer, sent me the pay scale and benefits package for its more than 500 employees, along with a brief statement. It said, in part, that Flying Food Group “has created hundreds of jobs in the Los Angeles area that offer great wages and benefits while providing a modern and safe work environment for everyone.”

The union does not agree and points out multiple findings in recent years by city, county and state agencies that safety standards and compensation requirements have not been met. Last August, the state labor commissioner fined Flying Food Group $1.2 million, alleging that the company had fallen behind in rehiring 21 California employees (18 of them in Inglewood) who were laid off during the pandemic.

To be fair, Flying Food's salary and benefits aren't bad. It's just that, given the costs of housing and other expenses, many employees end up traveling long distances and working into old age and advanced illness. At Garcia's workplace, 34 of his colleagues are 65 years old or older, and 14 of them are 70 years old or older, according to the union.

One of the union's goals, in addition to $25 an hour, is a pension plan. My first thought was that everyone would like to have pensions, but they are a thing of the past. And many companies operate on thin margins, so higher pay packages can lead to fewer jobs.

But we can't let profitable employers or the government get away with seniors' continued march toward abject poverty. When I interviewed New School economics professor Teresa Ghilarducci for her column on hotel employees last year, she said that pensions and lowering the Medicare age would go a long way toward easing their burden.

Salud García's day includes several hours of transit and eight or nine hours of work.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

I'm going to go out on a limb and assume that neither of those ideas can be considered viable at this time, but in written testimony Earlier this year, before a US Senate committee, Ghilarducci laid out a stark view of what he called America's “seriously failed” retirement system, which lags shamefully behind countries that have not failed their elders. .

“By international standards,” he said, “senior poverty in the United States is remarkably high: 23% of American seniors are poor; In Canada, the senior poverty rate is 12%; In the United Kingdom, the poverty rate for older people exceeds 15%; in France, 4.4%; and in the Netherlands (whose pension system is consistently among the best in the world) only 3.1% of older people are poor.”

García manages, but only because he keeps working. She and her late husband separated many years ago, she told me, and for a time she worked two jobs to support her children, one of whom died at age 30 of heart disease.

One night, outside his apartment in Reseda, after another 14-hour day, I noticed that Garcia was limping. He said his left knee was bothering him from long days emptying the food carts that flight attendants push down airplane aisles. Garcia said she puts dishes in dishwashers that sometimes leak, leaving her standing in puddles.

García shares her apartment and shares the bills with her son Brígido, 40, a physical therapist who told me that his mother's advice has been constant over the years.

“Never give up. Life is hard as we know it. We have to show everyone that we can do it,” he said.

That's the spirit his mother brought to the picket line in Inglewood one day. García took his colleagues out to the street during their lunch break, where they took up signs and asked for a new contract.

“One day I asked him, 'Why don't you retire?'” he said. Rafael Leon, a Flying Food dishwasher turned union representative whom I met in 2015, when he and his family lived in a converted garage. “She said, 'Son, if she leaves this job, it will be a death sentence.'”

She's fighting for the youngest employees, she told him, because they're the ones who will benefit the most.

As García told me:

“I want to carry this out. We are going to fight until we finish.”

If you are working late due to financial necessity, or know someone who is, please let me know at [email protected]