California has officially entered the era of climate-driven economic insecurity.

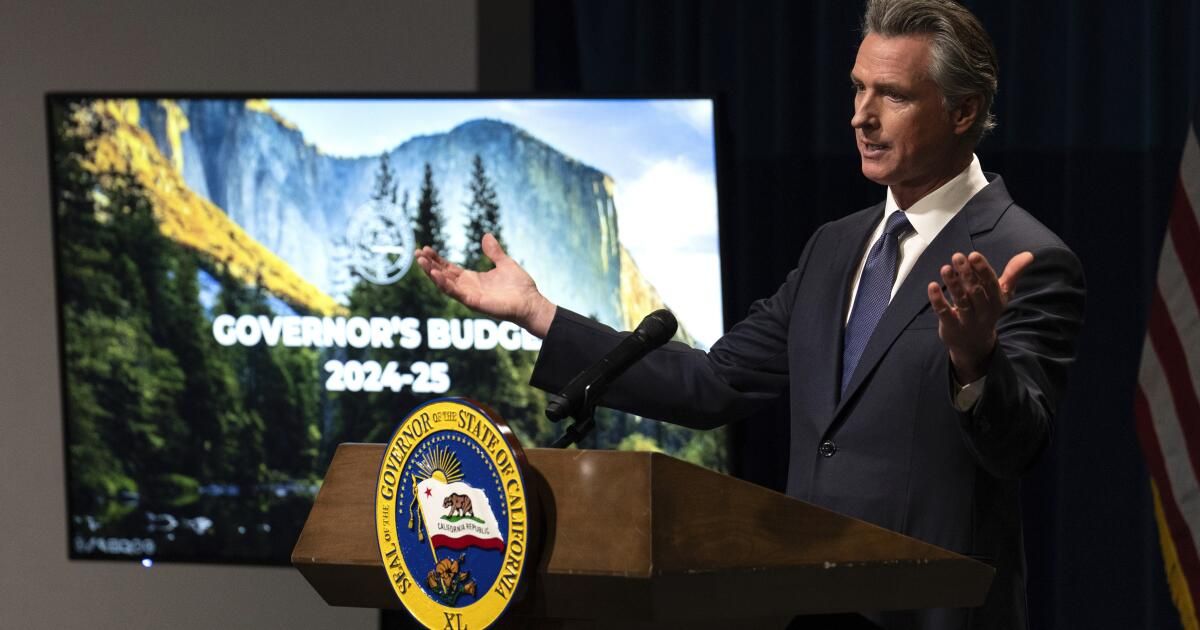

On Wednesday, Gov. Gavin Newsom unveiled his new budget, facing a nearly $38 billion deficit.

That missing money is mainly due to lower-than-expected tax revenues on capital gains: The gains on stocks and investments by the Golden State's wealthiest people weren't exactly what was expected.

But unlike most years, when state officials know in April, when taxes are usually filed, how much money California can responsibly spend, last year was different.

Mother Nature pummeled the state in winter and spring with record snowfalls and storms that flooded entire towns like Planada and Pájaro. Capitola was hit by a bomb cyclone that virtually destroyed the dock. Tulare Lake reappeared in the Central Valley, submerging homes and crops and revealing the fragility of an expensive levee. Damage caused by that extreme weather cost $4.6 billion and claimed 22 lives, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information.

Our weather was so volatile and devastating that even the IRS showed mercy and delayed the deadline for most state residents to file their taxes first to October and then to November.

Which meant that no one really knew (although there were certainly indicators) how much we were spending that we didn't really have until a couple of months ago, when those taxes were finally counted and came up short.

“This has been a difficult year,” Newsom told reporters gathered to hear his plan, and no one disputes it.

But it may also not be an unusual year, as we move toward the economic realities of climate change. Sure, the stock market is expected to go up, inflation will go down, and employment numbers will go up. By every measurable standard, the California and U.S. economies are poised for a good year, regardless of public sentiment that, faced with higher bills and a lingering sense of uncertainty, is not quite ready to take a positive outlook.

But the severity of our climate is not likely to abate, and dealing with the unrelenting toll of storms, floods, fires, sea level rise, extreme heat, mudslides and more will change what we can and can't afford in California. . Consumers already see this with home and auto insurance: Rates are rising based on projections of more climate disasters in the future.

At the same time, the costs of rebuilding or maintaining homes in high-risk areas are also rising, whether in places where the sea is encroaching on mansions or where flames threaten double-widths in fire-prone forests. Even keeping those homes warm or cool is increasingly difficult to afford.

That means it's harder to stay in housing at any income level. More than 3 million Americans, mostly in storm-affected states like Texas and Florida, have already moved because of the weather, a climate migration trend that is expected to increase as the cost of living in dangerous and devastated places rises. become unsustainable.

The federal government recently released its National Climate Assessment, which details the many ways the climate and the economy are linked, and the many ways the situation will likely get worse.

In the 1980s, the report says, “the country experienced, on average, a billion-dollar (inflation-adjusted) disaster every four months. Now, on average, there is one every three weeks.”

Every three weeks, a billion-dollar disaster. In recent years, that added up to $89 billion. And those billions of dollars don't include the emotional and economic costs of deaths and injuries, traumatized families, literally vanishing generational wealth, poor communities – often people of color – left without clean water or roads.

However, the costs of climate change are not just the obvious ones. Newsom's budget has cuts, although in the coming months the governor and the Legislature will have to debate exactly what they will be. Newsom suggests cutting spending by $8.5 billion, most of which would come from climate programs. But housing programs, the middle-class scholarship fund and other cuts that are likely to be unpopular would also lose money.

Newsom also suggests taking $13 billion out of our rainy day fund, which makes sense, though it's also likely an unpopular move.

But it has been a rainy year.

If anything can be learned from Newsom's proposal, it is that we should plan for more rainy years, with more intensity.

This year, that means “tightening your belt,” as Newsom said. A $39 billion deficit is painful, but not insurmountable.

But we need to save more in our reserve funds to plan for disasters we know are coming, which seems like common sense but is nearly impossible under existing rules. I won't bore you with the details of the Gann Limit, but suffice it to say that saving more in high-income years is difficult because of a budgeting rule established in the 1970s, long before billionaires with stock portfolios rivaled the wealth. of small nations became California's main source of income.

While our reserve fund is strong, states, including Wyoming, which also has a volatile revenue model, have much stronger funds than ours. Wyoming could run for almost a year with the money saved. Obviously, California is bigger, but we've saved just enough to last less than three months.

Projecting future income, for individuals and for states, is always something of a crystal ball task. But climate change is going to cost us dearly, one way or another.

California should start saving now for what is an inevitable debt to come.