As a baseball player, Willie Mays was arguably the greatest of all time – the GOAT of baseball. But he also starred in another endeavor: being an important civil rights pioneer in California.

Mays never wanted to be an activist for anything outside of the baseball diamond. But the racism she encountered after moving to San Francisco galvanized others to take up her cause and ultimately helped motivate city and state governments to ban housing discrimination.

His role began when Mays arrived in San Francisco from New York with the Giants baseball team in late 1957. Locals in supposedly enlightened San Francisco welcomed the star outfielder while trying to exclude him from a white neighborhood.

Mays publicly downplayed it, but his wife, Marghuerite Mays, spoke to reporters: “In Alabama, where we come from, you know your place. But up here everything is a lot of camouflage. They smile in your face and fool you.”

Willie Mays receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama at the White House in 2015.

(Evan Vucci / Associated Press)

Never mind that Mays was on his way to the baseball Hall of Fame as the greatest player in history. I do not care. If a black man were allowed to buy a home in a desirable neighborhood adjacent to fashionable St. Francis Wood in the Sunset District, nearby property values would fall. At least that's what white neighbors openly feared.

“I happen to have some properties in the area, and I stand to lose a lot if people of color move there,” a nearby homebuilder told reporters.

Yes, that's what San Francisco was like (in fact, pretty much all of California) until laws were passed in the 1960s to stop that discrimination. The turnaround was aided significantly by indirect help from Mays, according to another legendary San Francisco Willie: former mayor and former state Assembly Speaker Willie Brown.

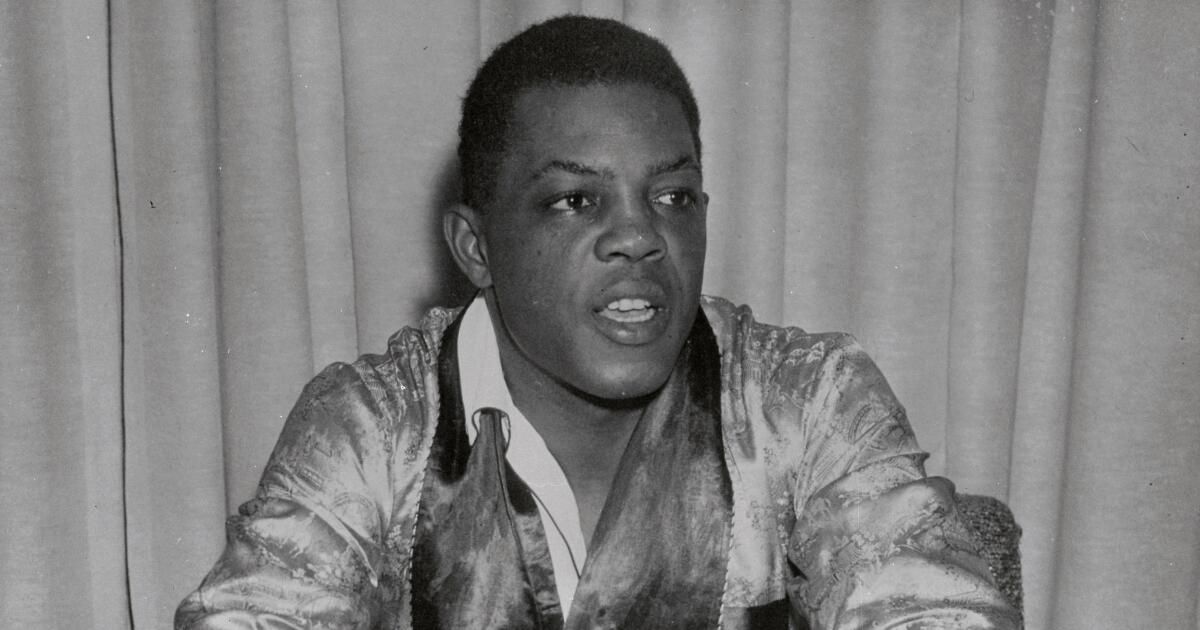

I called Brown, 90, after Mays died this week at age 93. Brown, a rare black lawyer in San Francisco in the late 1950s, struck up an early friendship with Mays.

“It was a joy, frankly. A fun guy,” Brown says.

Brown credits racial bias against Mays for prompting the city to adopt an ordinance prohibiting housing discrimination.

“It all started with Willie Mays,” Brown told me. “As a result of his rejection, the newspapers suddenly became aware of the racism in San Francisco.

“San Francisco was not racist like other parts of the country. “People were smiling.”

Brown continued: “San Francisco's fair housing law was passed because Mays was denied the right to housing. That intensified the need to change. “It was the most dramatic example of how discrimination was practiced against people of color.”

In 1963, pushed by Governor Pat Brown and Bay Area legislators, the state legislature passed a bill prohibiting racial discrimination in the sale and rental of housing. He needed all the support he could muster and generated the biggest, most bitter political fight I have ever witnessed in Sacramento.

California voters overwhelmingly repealed the law the following year. But the repeal was ruled unconstitutional by both the state court and the U.S. supreme court.

Mays was not personally involved in that fight, but Brown certainly was.

A transplant from Jim Crow to East Texas, Brown became a civil rights activist in San Francisco when Mays arrived from New York. In fact, Brown was persistently snubbed by real estate agents when he tried to buy a house in 1961. He responded by leading a sit-in at a real estate agent's office.

Mays' incident occurred after he offered the asking price of $37,500 for a three-bedroom home in an upscale, tree-lined, all-white neighborhood. After waiting several days, his offer was rejected. The house remained on the market for the same price, but not available to the star player.

The San Francisco Chronicle found out about the rejection and published this banner at the top of page 1: “WILLIE MAYS IS DENIED SF HOUSE-CAREER PROBLEM.” The headline of the article read: “Willie Mays Rejected at SF House-Negro.”

“I didn't think I'd have so much trouble trying to buy a place,” Mays told a television reporter. “When I go looking for a house, I don't worry about who lives next to me.”

Unlike the nervous whites of that era.

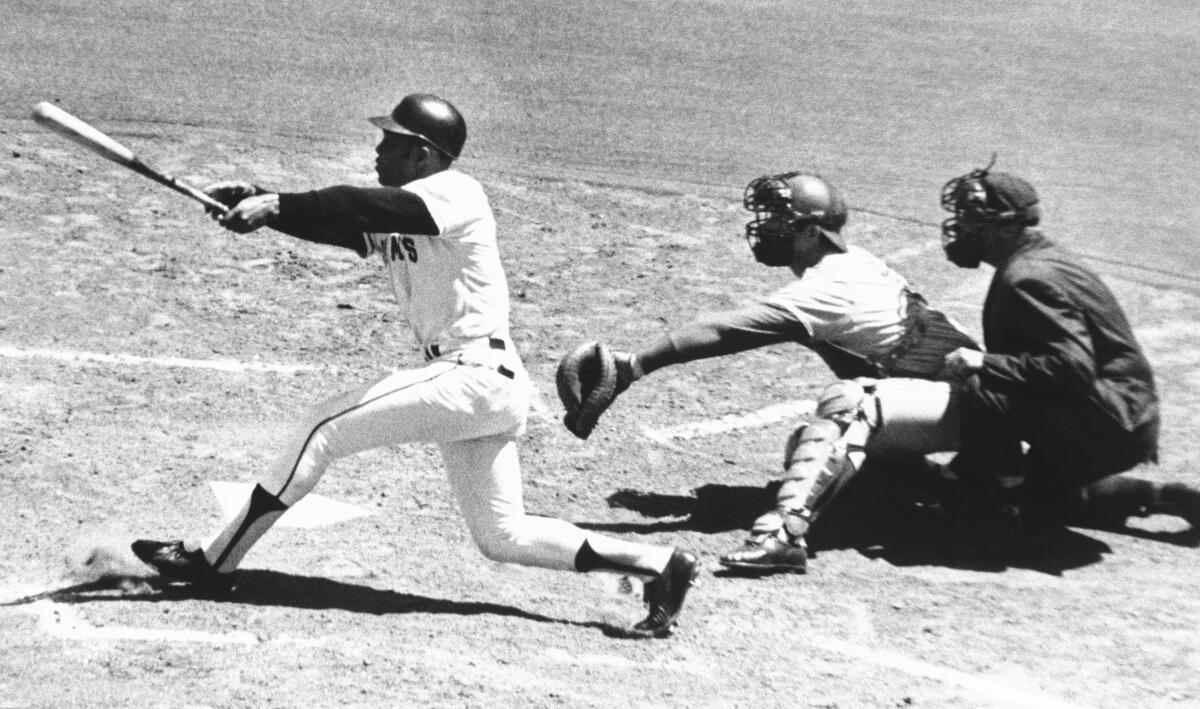

Mays gets his 3,000th career hit, a single to left, at San Francisco's Candlestick Park in 1970.

(Robert H. Houston/Associated Press)

San Francisco Mayor George Christopher, a moderate Republican, when that race existed, offered to let Mays and his wife live temporarily in his house.

In the end, the owner backed down, despite being reprimanded by neighbors. Mays moved out. And almost immediately someone threw a brick through a window.

Mays kept his mind on baseball and eventually became the pride of San Francisco.

As a senior sportswriter for United Press International, I had the privilege of watching many Giants games at windy Candlestick Park in the early 1960s.

Mays' stats are phenomenal: a career .301 batting average, 660 home runs, 3,293 hits, 339 stolen bases, 12 Gold Glove awards in center field, 24 All-Star Games.

In the 1961 All-Star Game at Candlestick that I helped cover, Mays doubled the tying run in the 10th inning and then scored the winning run on a single by Pittsburgh's Roberto Clemente as the National League beat the American League, 5- 4.

But scores and statistics tell only part of the story of Mays' greatness.

What I remember most about him is his play with euphoria and exuberance, galloping around first base, always with the threat of turning a single into a double and a threat of stealing second in any case. At full speed regardless of the score. He cap flying.

In his long post-career period, Mays provided a comfortable nostalgic link to baseball's exciting heyday, before the dull analytics and emphasis on astronomical free agent salaries.

America cannot afford to lose those people. He didn't hate. He brought joy.

And, although there are no statistics on the matter, it helped combat discrimination in housing.