When Erika Flores applied for an internship at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 2014, she wasn’t quite sure whether her undergraduate work in environmental science would fit in at a place known for working in much more distant locations.

“I wanted to fix our planet,” Flores said recently. “I never imagined myself studying outer space.”

Aggressive and shocking reports on climate change, the environment, health and science.

Not only did she get the internship at La Cañada Flintridge Institution Laboratory of Origins and HabitabilityBut his contribution there also began an ongoing partnership between Cal State Los Angeles's civil engineering department and a lab dedicated to understanding how life begins.

“I didn’t see myself in an astrobiology lab,” Flores said from her office at the Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts, where she has worked since 2023 as an engineering associate.

But it turns out that understanding how microorganisms got into Earth's water is valuable knowledge for those tasked today with cleaning up that supply, his mentor at JPL said.

“There’s a lot of overlap between wastewater and astrobiology,” said Laurie Barge, a JPL scientist who co-directs the Origins and Habitability Laboratory with research scientist Jessica Weber. “It sounds strange, but it’s true.”

JPL scientist Laurie Barge talks with interns at JPL's Origins and Habitability Laboratory.

(Dania Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

This symmetry between the biology of our home planet and more distant worlds has led to a partnership between Barge and Weber's lab and that of Flores' former adviser, Arezoo Khodayari, an associate professor of civil engineering at Cal State LA.

After nearly a decade of collaboration, Barge and Khodayari recently received a NASA grant that will cover up to six internships in the lab for Khodayari's students over the next two years.

The prize is One of 11 that NASA's Science Mission Directorate conducted with universities that have not traditionally been part of the process that brings new scientists to the space agency.

1

2

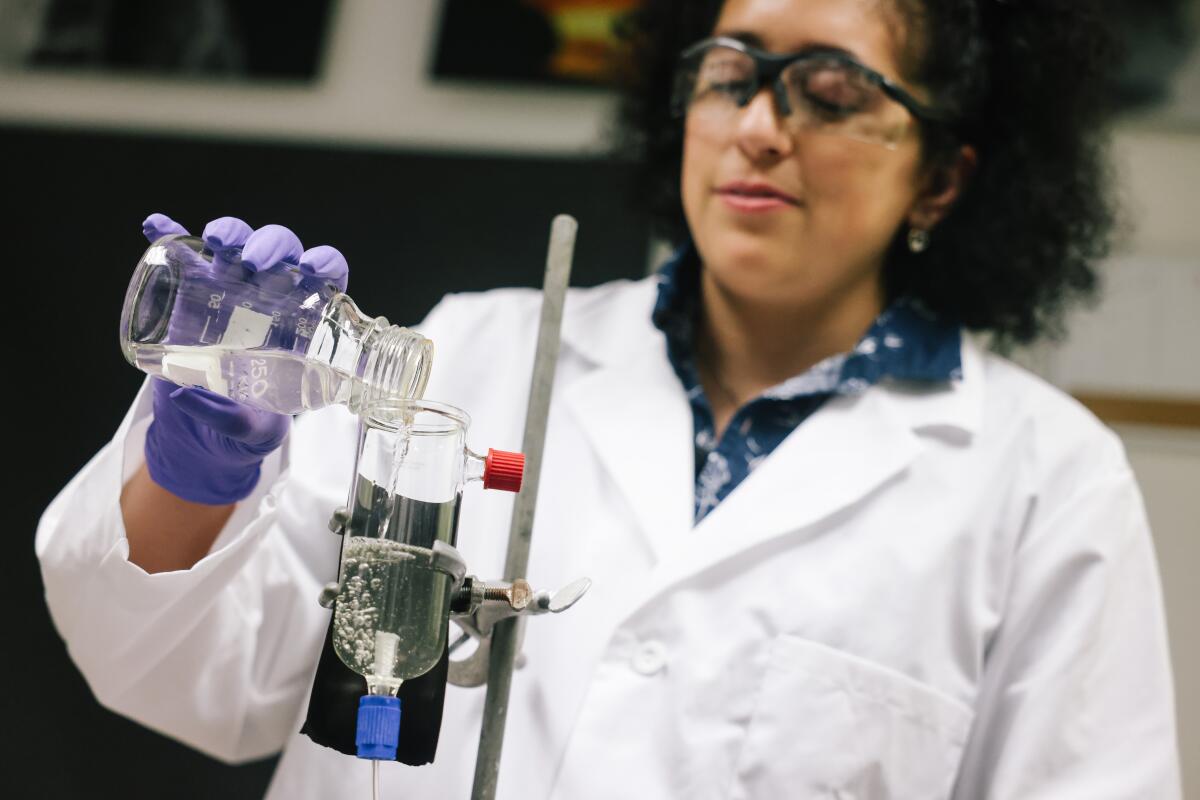

1. Cal State LA students Julia Chavez, left, and Cathy Trejo conduct an experiment that simulates oceans on early Earth and possibly other planets. (Dania Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

“We are intentionally increasing equitable access to NASA for our nation’s best and brightest talent,” Shahra Lambert, NASA’s senior advisor for engagement, said in a statement.

The two scientists connected through Flores who, with Barge’s encouragement, decided to pursue a master’s degree at Cal State LA during his internship at the Origins and Habitability Laboratory.

While Khodayari’s research at Cal State LA’s Pollution Control and Environmental Sustainability Lab focuses on managing contaminants here on Earth, she and Barge immediately saw parallels with the Origins and Habitability Lab’s exploration of the conditions that could give rise to life throughout the universe.

“The fate of these chemicals in an aqueous environment is relevant to both fields,” Khodayari said. “All of these different projects have chemistry in common.”

Following the success of Flores’ internship, the two scientists began looking for ways to introduce planetary science to students who might not have considered it part of their education and lacked access to the tools necessary for sophisticated research.

Cal State LA's Arezoo Khodayari has collaborated with JPL for years to bring interns to NASA's Southern California center.

(Dania Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

Eduardo Martínez was studying for a master’s degree in civil engineering in 2018 when Khodayari called him into her office and asked if he would be interested in working for JPL.

“I was a little taken aback,” recalled Martinez, who was born in Mexico and raised in Los Angeles. “I thought, ‘JPL? How? ’” he “Jet Propulsion Laboratory?”

He was immediately hooked. As a civil engineering student, Martinez had become interested in how phosphorus and nitrogen affect water quality, causing algae blooms and low oxygen levels when dumped in large quantities into freshwater. During the internship, he was lead author of a research paper with Barge, Khodayari and others on how nitrates react with iron compounds in aqueous environments.

His work in the Origins and Habitability Laboratory showed him that the same elements also play a crucial role in the formation and maintenance of life, and are therefore a key point of interest for NASA astrobiologists. “I hadn’t made that connection before, and it was fascinating to see it,” Martinez said.

The experience inspired him to pursue a PhD in geosciences at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. His research there focuses on how certain isotopic compositions in clay minerals might indicate past life in samples brought back from Mars.

Julia Chavez and Cathy Trejo greet each other at JPL. They are two of several Cal State LA students who are interning at JPL's Origins and Habitability Laboratory.

(Dania Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

Since Flores made the move from environmental science to space, five Cal State LA students have interned at JPL. The NASA grant will accelerate that process, introducing more students to research opportunities that might not have otherwise crossed their paths.

This summer, interns Julia Chavez and Cathy Trejo donned protective goggles and white lab coats to inject fluids into an iron chloride solution. The experiment replicates the reaction between seawater and material rising through hydrothermal vents, a source of energy for life on Earth and a possible mechanism by which organisms first developed here.

“Five or six years ago, I couldn’t imagine myself working in research,” said Chavez, who completed his master’s degree this year. “Being here, I couldn’t imagine a different path.”