For years, Paul Banke desperately needed the money he believed California owed him.

The former world super bantamweight champion boxer had been battling cancer treatment and had to sell his car when the broadcast went out during the pandemic.

Banke, who made headlines in 1995 when he became the first major U.S. boxer to publicly acknowledge that he had AIDS, was certain he was owed a pension from California's exclusive boxer's retirement system. But Banke said the California State Athletic Commission, which administers the 40-year pension plan, told him repeatedly over the years that he didn't qualify.

On Monday, after numerous investigations by the Times, the commission admitted that it had inexplicably lost Banke's pension records and voted to pay him a lump sum of $21,000. Unable to calculate precisely what Banke is owed, the commission approved an amount equal to the average payout to boxers over the past three years.

“I don't know if they are defrauding him or if we are overpaying him. I don’t know,” Andy Foster, executive director of the commission, told The Times. “Based on the information I have, this is the fairest way I can see to pay you.”

The commission said the lost pension was probably an “isolated incident” but could not rule out other boxers being affected.

Monday's commission vote followed questions from the Times over the past six months about why Banke had been denied a pension when boxing records showed he had fought more than twice the minimum rounds in California to qualify. It also follows a Times investigation last year that found the pension program failed in its primary mission of locating and informing boxers of their benefits, kept inadequate records and had not set aside enough money to pay pensions it owed.

Foster said Banke's pension records did not appear to have been transferred when the California Professional Boxers' Pension Plan was reviewed in the 1990s.

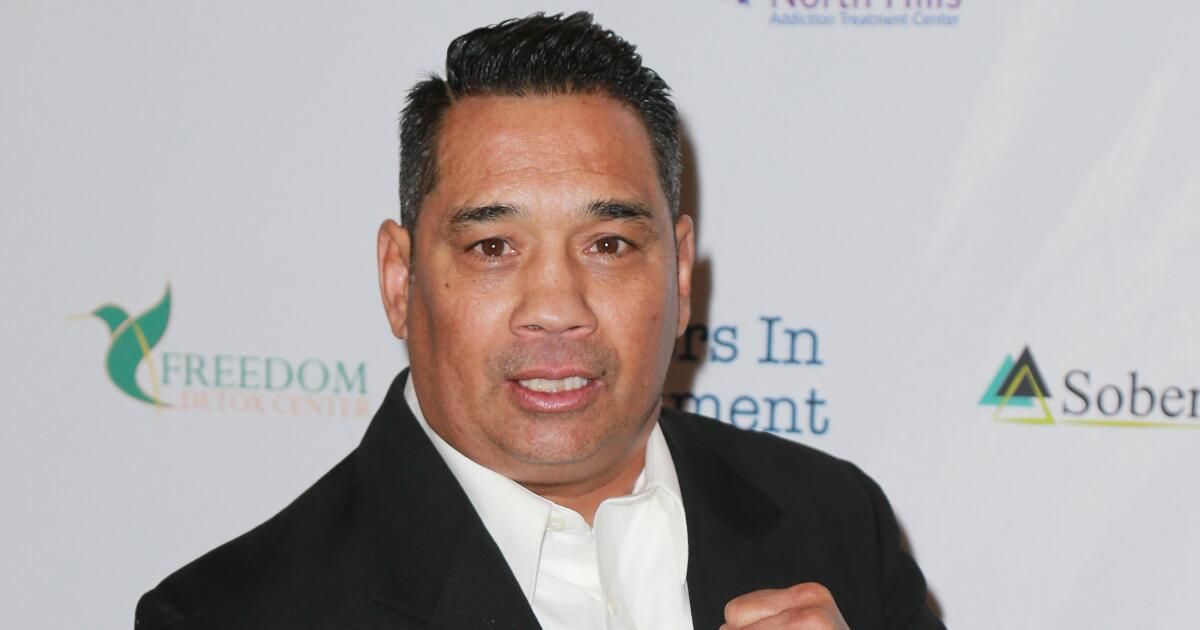

Banke was a hard-hitting hitter who defeated Daniel Zaragoza in 1990 to win a World Boxing Council title at the Inglewood Forum. That year, The Times described Banke as a “crowd-pleasing slugger.”

Banke, now 60, lives on Social Security disability insurance in Pasadena with his dog and birds. She said the pension money will allow her to buy a car.

“This is a lot of money for me,” Banke said.

The plan offers pensions to any professional boxer, regardless of residency, who has completed at least 75 scheduled rounds in California with no more than a three-year break. The pension amounts are determined by the number of rounds the boxer fought and the size of the purses. Boxers can claim their pensions from age 50, or earlier if they use them for medical or educational purposes.

Andy Foster, executive director of the California State Athletic Commission, at a meeting last year.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

The plan, funded by a fee of 88 cents per ticket, was created in 1982 to provide a “minimum of financial security” to retired combatants, according to state statute. More than $4.5 million has been paid to 265 retired fighters, with most of the claims occurring in the last decade. The average pension is a one-time payment of $17,000.

Dozens of boxers told The Times in interviews over the past year that they did not remember ever receiving information about their pension accounts during their careers and criticized the state for not making more efforts to find them. Following the Times investigation, the commission pledged to step up efforts to track down the boxers and paid out a record amount of pensions last year. However, even with the increased payments, fewer than 1 in 4 boxers who could claim pensions did so last year, according to The Times' analysis of commission documents.

Banke said he called the athletic commission several times over the past 10 years and each time he was told he didn't qualify. Following the Times investigation, Banke's friends told him to keep pressing the commission to explain why he was being rejected. Banke said he wasn't getting anywhere before contacting the Times.

“It's alarming,” said Héctor Lizárraga, a featherweight champion who filed for his pension last year after being contacted by The Times. “I told him he had to be persistent and keep asking. It is unacceptable. It's not that he's a fighter. “We are talking about a former world champion.”

Foster said there could be other boxers who are owed pensions for whom the commission has no records, but he has doubts.

“I mean, there could be, but we did a little checking and I can't find any,” Foster said. “We were a little worried about that. But there may be another one, I don't know. But I think this is kind of an anomaly.”