There was gold in these hills.

Tucked away in the rugged Sierra Nevada mountains among sprawling pine forests, Havilah was once a bustling mining town where stamp mills pulverized rock from the region's mines and prospectors searched for precious metals in the late 19th century.

In its heyday, the town's main street was home to saloons, dance halls, inns and gambling houses. Townspeople witnessed midday gunfights, chases of wanted people for murder and stagecoach robberies, and wagered gold dust on horse races, according to Los Angeles Times archives.

But for nearly a century, long after the frenzied search for gold had died down, Havilah had been considered something of a ghost town, with only about 150 residents. The foundations were all that remained of most of its historic buildings when fire swept through the town on July 26.

The fast-moving Borel Fire, which had burned nearly 60,000 acres by Friday, destroyed some of the last vestiges of Havilah in just 24 hours, including a replica of a courthouse that served as a small roadside museum for decades.

Aggressive and shocking reports on climate change, the environment, health and science.

Roy Fluhart, whose ancestors had settled in the area during the Great Depression, had sought to preserve the town's rich history. As president of the Havilah Historical Society, he and his relatives helped preserve the courthouse with historical documents and photographs, old mining tools and other artifacts from the region's past.

“We lost everything,” Fluhart said. “The sad thing is that the museum was an archive and now it’s lost. Damn. We didn’t really have time to get anything out.”

It wasn't just the city's history that was lost.

Havilah resident Bo Barnett, wearing the same clothes he was wearing when he fled, recounts escaping the Borel fire. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

Bo Barnett, whose home was destroyed, managed to escape with his dogs and the clothes he was wearing. Barnett, whose wife died a month ago, expressed regret that he had not had time to collect her ashes.

“It was raining fire on us,” Barnett said, his eyes filling with tears. “I wasn’t sure what I was getting into. My tires were melting on the road. It was horrible.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom, who spent much of his childhood in the sparsely populated mining community of Dutch Flat in Placer County, mourned the loss of another gold rush community Tuesday. Wearing aviator sunglasses and a baseball cap, he walked through the rubble in Havilah, approached the remains of the town’s museum and pulled an Uncle Sam piggy bank from the blackened debris.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom toured Havilah after the fire and found an artifact among the remains of the courthouse museum.

“Towns that have disappeared from the map — places, lifestyles, traditions,” Newsom said at a news conference. “That’s what it’s really about. At the end of the day, it’s about people, it’s about history, it’s about memories.”

In recent years, devastating wildfires have ravaged some of the California gold rush towns, erasing the history of one of the most significant eras of 19th-century America. Havilah joins other communities such as Paradise and Greenville, small communities that saw the arrival of gold seekers, followed by an exodus of population and, more recently, devastation.

Havilah traces its origins to Asbury Harpending, a Kentuckian who plotted to seize California and its gold to support the Confederacy during the Civil War. In 1864, Harpending, outraged after his conviction for high treason, ventured into the Clear Creek region of present-day Kern County. He found gold deposits and named the area Havilah, after a gold-rich land in the Book of Genesis.

Although Harpending had no claim to the land, he established a sprawling mining camp and sold parcels to arriving miners, in what many believed might be a second gold rush. In 1866, Havilah became the county seat of the newly created Kern County, a title it held for eight years until Bakersfield became the principal city. He stayed only two years, but made a fortune: $800,000.

“I was literally raised from absolute poverty and brought into possession of nearly a million dollars,” Harpending wrote in his autobiography. “I discovered a great mining district and founded a prosperous town. And if the question of paternity is ever raised in court, it will probably be proved to the satisfaction of the jury that I am the father of Kern County.”

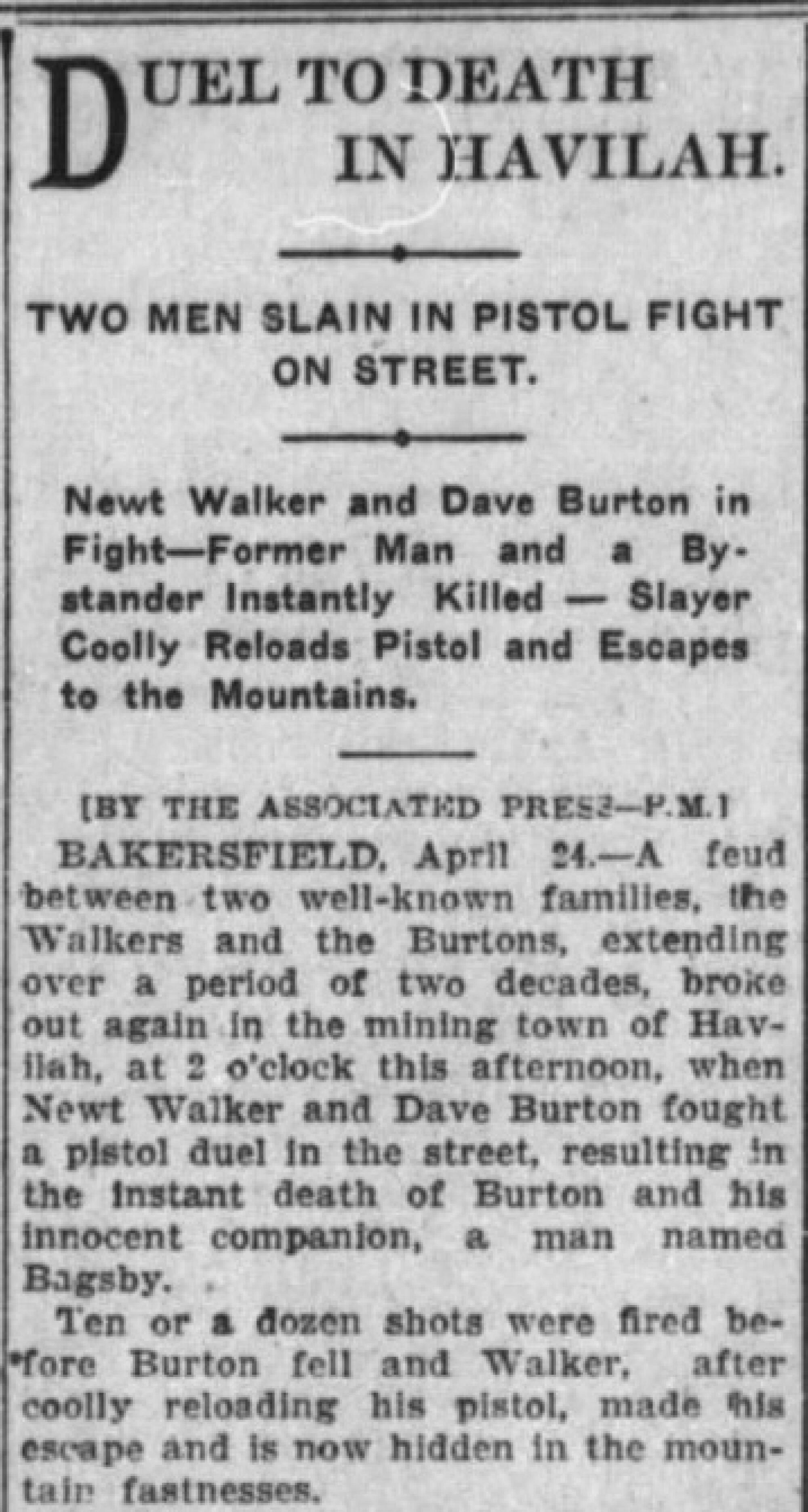

A 1905 article in the Los Angeles Times details a gunfight reminiscent of an Old West movie.

(Los Angeles Times archive / newspapers.com)

As gold became harder to find, people abandoned Havilah and its buildings fell into disrepair. Those who remained attempted to commemorate the community's mining legacy and pioneer heritage. In 1966, for the centennial of Havilah's founding, residents finished building a replica of the courthouse. They later built a replica of the town's school, which also functioned as a community center.

Historic markers along the Caliente-Bodfish Road indicate buildings that once existed: a barber shop, a blacksmith shop, the Grand Inn and a horse stable. Some large plaques also pay tribute to historic events such as the last stagecoach robbery in Kern County in 1869, in which a gunman made off with $1,700 in gold coins and bullion.

Wesley Kutzner, a member of the historical society and Fluhart's uncle, helped build the courthouse replica along with his parents and other neighbors. Although the historical society couldn't afford fire insurance, Kutzner said he has decided to clean up the property and rebuild it, the same way the community did nearly 60 years ago.

“The plan is to rebuild,” Kutzner said. “It will be a community effort. The road back will be difficult, but we will get there.”

One resident who plans to rebuild is Sean Rains. He left Bakersfield two years ago and moved to Havilah with his girlfriend and pit bull, seeking the quiet of the mountains. Rains, a miner and countertop manufacturer, had also been one of the few people who harbored hope of finding buried treasure in Havilah.

In his front yard, Rains had a shaking table and other equipment to sift the earth for gold particles.

“It wasn’t anything that made us rich,” he said, but he did find something.

“They say it’s everywhere,” Rains said. “It’s just a question of whether it’s enough to make it worthwhile.”

1

2

3

1. Sean Rains moved to Havilah two years ago and began panning for gold using a vibrating table in his front yard. 2. A roadside scene in Havilah. 3. Melted film canisters lie on the floor of the Havilah museum, just some of the artifacts lost in the Borel fire.

Rains was also recruited by the historical society. He read old letters in which one sheriff had remarked that the town's only pastimes were robbing stagecoaches and horse racing. Another recalled how pioneers would drag their carriages over the mountainous terrain with ropes.

The historical society had recently installed a water hose at the school replica. Since Rains lived nearby, he was asked to help defend the school in case a fire broke out.

“I gave them my word,” he said.

So when Rains saw the fire cresting the mountain behind his house and rapidly descending into the valley, he ran to the house next door to start the school's water pump. He doused the building and extinguished the embers under the front porch.

He eventually focused on his single-story home and sprayed the fire until the trees in his yard were ablaze. He, his girlfriend and their dog sped off in their pickup truck.

“It was right on top of us as we were leaving here,” Rains recalled. “It was right on top of us. The winds were so strong, they were blowing in all directions. It was ripping branches off the trees. The whole mountain was swallowed up.”

Rains returned to town the next morning, walking along the Caliente-Bodfish Road to see what remained of Havilah.

The valley's pines and oaks were charred, and much of the landscape was covered in white ash. Rains' two-bedroom home was burned to its cobblestone foundation. Two cars he had been restoring were reduced to charred husks. His two all-terrain vehicles were reduced to skeletons.

The school survived.

Havilah school, after the fire.