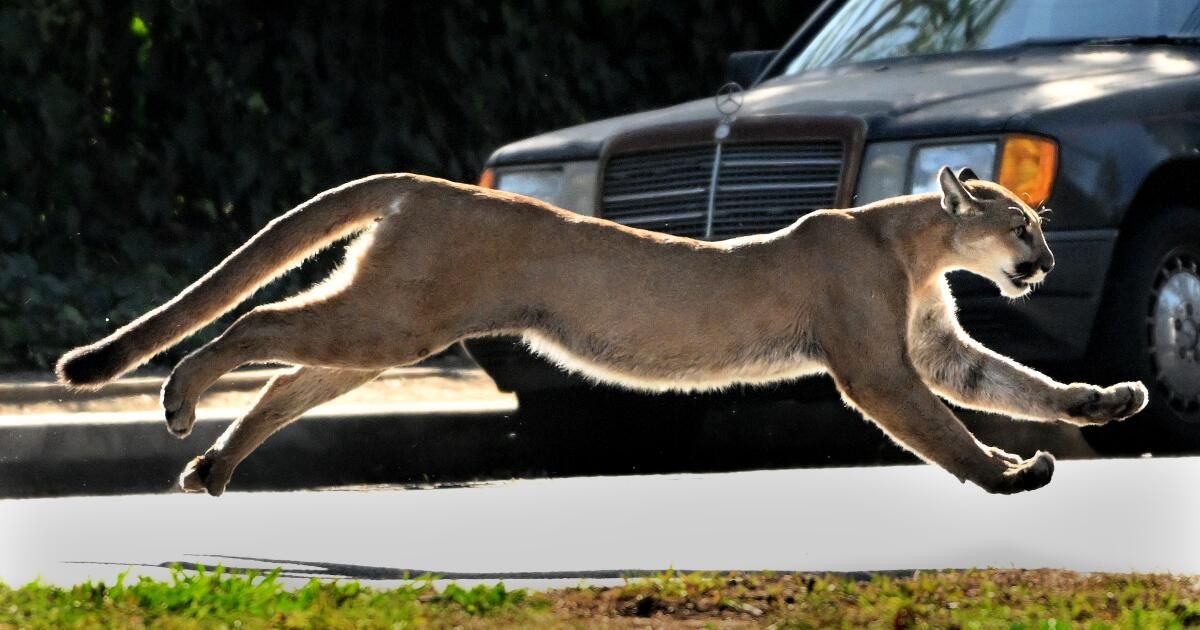

Scientists have completed the first comprehensive estimate of cougars in California, a vital statistic needed to shape cougar-friendly land use decisions and ensure predators can find space to roam, mate, and find prey.

The total number of pumas is estimated to be between 3,200 and 4,500, thousands fewer than previously thought. The count was conducted by state and university scientists who used data from GPS collars and genetic information from fecal samples to model population densities in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the Mojave Desert and the mosaic of brush and wilderness areas devastated by the Southern California fire.

“The highest density is in the coastal forests of Humboldt and Mendocino counties in northwestern California, and the lowest is the high desert east of the Sierra Nevada mountain range in Inyo County,” said Justin Dellinger, large carnivore biologist and leader of the California Mountain Association. Leon Project Effort. “The Central Valley and parts of the Mojave Desert have no mountain lions.”

Two orphaned mountain kittens snuggle in a carrying box on their way to the Oakland Zoo in November 2023.

(Oakland Zoo)

Experts will review a report on the project’s findings before publication in a scientific journal later this year.

“There has never been a study of this scale and over such a large and diverse geographic area with such a variety of habitats,” said Winston Vickers, study co-author and veterinarian at the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife had estimated for decades that the state’s mountain lion population was about 6,000, even despite relentless vehicle attacks, wildfires and encroachment by land-hungry humans throughout its range. of distribution.

“That old figure was just a rough estimate without much data to back it up,” Dellinger said. “The new, more accurate information we collect will be used to more appropriately conserve and manage mountain lions.”

In a collaborative effort involving the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, UC Davis, UC Santa Cruz, the nonprofit Institute for Wildlife Studies and the nonprofit Audubon Canyon Ranch, Dellinger and others toured mountain forests, canyons and desert wastelands in search of tracks. They also set up trail cameras and traps, tranquilized the lions, took biological samples and placed tracking collars on the animals.

A motion-activated camera captures an image of a mountain lion in Joshua Tree National Park.

(Joshua Tree National Park)

Dellinger said the group spent approximately $2.45 million in state funds over seven years to produce three population estimates: one suggests there are 4,511 mountain lions living in California, and the other two suggest the number is approximately 3,200.

Deciding which figure is more accurate will be a challenge for biologists tasked with reviewing the census report.

They already agree on one thing: humans are the biggest threat to pumas. In California, about 40 million people live in or adjacent to mountain lion habitat.

Cougars as a species are not listed as endangered. But in Southern California, vehicle collisions, rat poison, inbreeding, wildfires, poaching, urban encroachment and highway systems are contributing to what scientists call an “extinction vortex.” .

There is a nearly 1 in 4 chance that the charismatic cats will become extinct in the Santa Monica and Santa Ana Mountains within 50 years.

The state Fish and Game Commission has granted pumas in six regions – from Santa Cruz to the US-Mexico border – additional protection under “candidate status” for listing as threatened.

2020 photo of adult female mountain lion P-65, which in 2022 was the first mountain lion in a two-decade-long National Park Service research study to die from complications of notoedral mange, a highly contagious skin disease. contagious caused by a mite parasite. .

(NPS)

The action came in response to a petition co-sponsored by the Center for Biological Diversity and the nonprofit Mountain Lion Foundation. He maintains that six isolated and genetically distinct puma clans within those areas make up a subpopulation that is threatened with extinction.

The commission is expected to make a final decision later this year.

“We look forward to providing cougars with the protection that is clearly warranted and desperately needed,” said Brendan Cummings, conservation director at the Center for Biological Diversity.

The effect of the designation would be far-reaching.

If the state Fish and Game Commission agrees, the state Department of Transportation would not be allowed to build or expand roads in prime mountain lion habitat without implementing adequate measures to ensure connections and safe passage over them.

Additionally, large-scale residential and commercial development could be prohibited or limited in cougar habitats within a region that covers approximately one-third of the state.

The new mountain lion population assessment comes at a time of continued efforts by the state Department of Fish and Wildlife to identify and prioritize barriers to wildlife movement across the state. It also comes at a time of growing support for wildlife crossings.

A view of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing construction site on Highway 101. The structure on the right holds a time-lapse camera to document the project.

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

One of those bridges is the $87 million Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, which is currently being built on a 10-lane stretch of Highway 101 near Liberty Canyon in Agoura Hills.

Meanwhile, officials are preparing new census campaigns to help guide development options in areas where conflicts with other large predators over territory are testing public strength.

“The state is trying to get a black bear census going,” Dellinger said. “Having as much data as possible is always better for managing species like that, especially in places where nature is overpopulated with people.”