After years of widespread declines, groundwater levels rose significantly across much of California last year, driven by historically wet weather and the state's increasing efforts to replenish depleted aquifers.

The state's aquifers gained about 8.7 million acre-feet of groundwater, nearly double Lake Shasta's total storage capacity, during the 2023 water year that ended Sept. 30, according to data recently compiled by the department. of California Water Resources.

A large portion of the profits, about 4.1 million acre-feet, came from efforts that involved capturing water from rivers swollen by rain and snowmelt, and sending it to areas where water seeped into the ground to recharge. the aquifers. The state said the amount of managed groundwater recharge that occurred was unprecedented and nearly doubled the amount of water replenished during 2019, the previous wet year.

Still, the rise in underground supplies follows much larger long-term declines, driven largely by chronic over-extraction in agricultural areas. The gains only partially recovered the estimated losses of 14.3 million acre-feet of groundwater during the previous two years of severe drought, when farms relied heavily on wells and aquifer levels plummeted.

“It was a good rebound,” said Steven Springhorn, supervising engineering geologist at the state Department of Water Resources.

“However, we have a large deficit of groundwater,” Springhorn said. “Overall, the trend has been downward for a long time.”

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

The Department of Water Resources published the information in its Semi-annual report on groundwater conditions. The report did not include data from late 2023 and early 2024, which will be assessed in the next update later this year.

In early 2023, a series of powerful storms ended three years of extreme drought, causing flooding and leaving one of the largest snow accumulations on record. The year was the eighth wettest statewide in the last half century.

Wet weather and the availability of canal-supplied water led agricultural well owners to pump less groundwater. Floodwaters spread and naturally replenished groundwater along rivers and wetlands. In some areas, local water agencies directed flood waters to specific recharge basins or agricultural fields, where the water seeped into the ground.

The majority of managed recharge efforts to date have occurred in agricultural areas of the San Joaquin Valley, where local agencies have been working on plans to combat overdraft and have made investments in infrastructure to transport water to recharge facilities. .

According to the report, water levels rose more than 5 feet in 52% of wells with available data, while there was little change in 44% of wells, and only 4% of wells decreased by more than 5 feet. feet.

However, over the past five years, most areas have experienced downward trends in water levels. The report's authors said this “underscores the fact that a single year, or even a few years, of heavy rainfall is not enough to replenish the state's depleted groundwater basins,” or offset a series of critically dry years.

Springhorn noted that researchers have estimated the losses of groundwater in the Central Valley by approximately 40 million acre-feet over the past two decades.

Since 2000, California has also received much less precipitation than the 20th century average. State water officials call this the “accumulated precipitation deficit,” which reflects repeated droughts and the worsening effects of climate change.

Central Valley farms have long relied on a mix of river water and groundwater to produce crops such as almonds, pistachios, grapes and hay to feed dairy cows.

Declining groundwater levels have left thousands of families with dry wells over the past decade. But after 1,494 dry wells were reported in water year 2022, the total fell to 669 dry wells the following year and has continued to decline.

The problem of land subsidence, which is related to the decline of groundwater, has also been greatly alleviated. Land subsidence affected smaller areas. Between October 2022 and October 2023, areas totaling approximately 800 square miles (largely on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley) experienced measurable ground surface “uplift” of more than 1.2 inches.

Springhorn said local agencies' efforts to increase groundwater had a positive effect.

“These numbers are great. And they really reflect a tremendous amount of work at the local level,” she stated. “But there is still much work to do to achieve sustainability in our groundwater basins.”

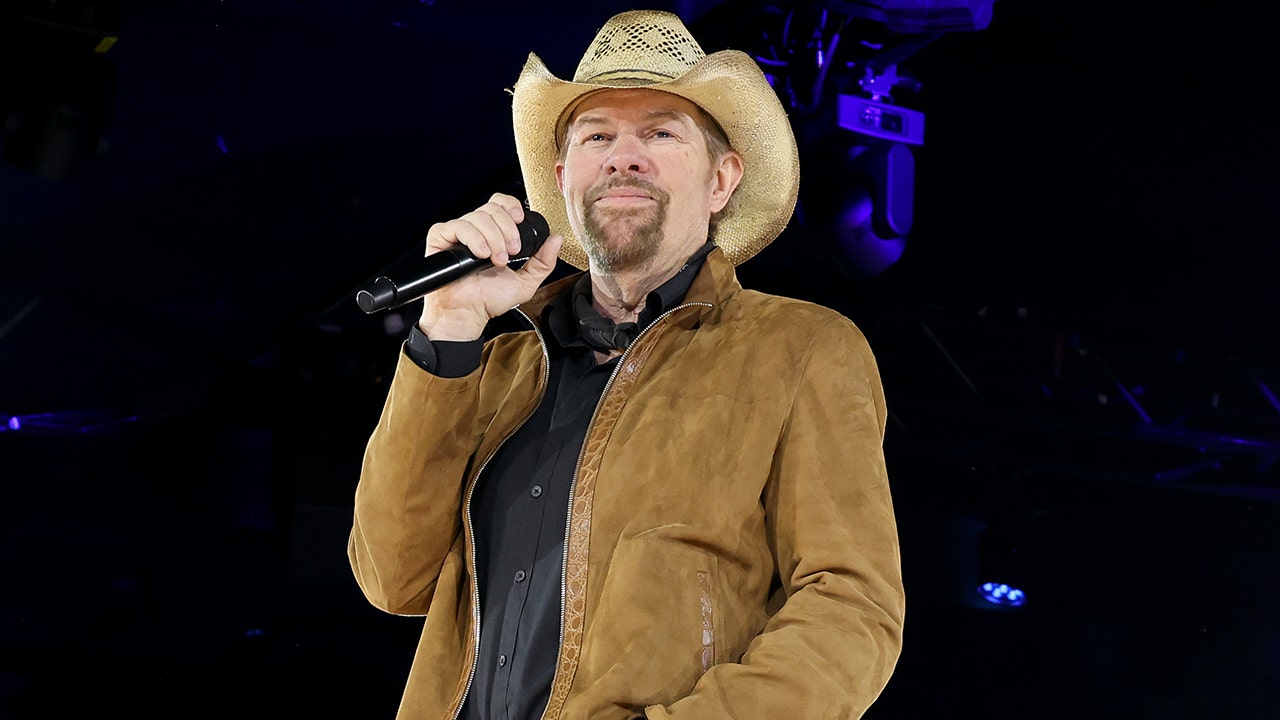

The birds will gather in 2023 at High Desert Water Bank near Lancaster, where the Metropolitan Water District uses water from the State Water Project to store groundwater for cities throughout Southern California.

(Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times)

He noted that this year California will celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. The landmark law requires local agencies in many areas to develop groundwater plans and curb overpumping by 2040.

In January, the Department of Water Resources finished reviewing local agencies' groundwater plans.

State officials have declared those plans inadequate in six areas of the San Joaquin Valley, and regulators last month voted to place one of those regions – Tulare Lake Subbasin – on “probation” status for failing to take sufficient action to address chronic overpumping.

Some of the areas where the state has declared serious overdraft problems, such as the Tule and Kaweah subbasins, are also among the regions that recharged aquifers the most over the past year.

“The impressive recharge numbers in 2023 are the result of hard work from local agencies combined with dedicated efforts from the state, but we must do more to be prepared to capture and store water when wet years arrive,” said Deputy Director Paul Gosselin. of sustainable water management of the Department of Water Resources.

He said that in light of the continued groundwater deficit, “we need to continue streamlining processes and investing in water management strategies and infrastructure, such as stormwater capture and groundwater recharge.”

The state agency has provided about $121 million to support dozens of local projects aimed at increasing groundwater replenishment.

California has also recently mapped large portions of the state's aquifers. Using a helicopter equipped with a ground-penetrating electromagnetic imaging system, state officials scanned up to 1,000 feet underground to map optimal areas for recharging aquifers.

The data can now be accessed to assist in planning locations for groundwater recharge. Officials hope to take advantage of channels left by ancient rivers, or what scientists call paleovalleys. These areas have coarse-grained sand, gravel, and cobbles that create highly permeable pathways to replenish groundwater.

“The more we understand where these preferential pathways, or fast pathways, are to the subsurface, the better they can be optimized” as areas to send water when it becomes available, Springhorn said. “It allows us to use this natural infrastructure that we have in California to adapt to climate change.”

Experts say replenishing groundwater alone will not be enough to address the problems of declining aquifers in areas with serious overdraft problems, and that meeting state-mandated goals in the coming years will also require substantial reductions in the pumping.

The last two wet winters have been good for the state's groundwater, and the recharge projects to date represent an important start to prioritizing further replenishment of aquifers, said Graham Fogg, professor emeritus of hydrogeology at UC Davis.

“This is literally just the tip of the iceberg in terms of potential,” Fogg said. “There is much, much, much, much more potential for managed aquifer recharge.”

For one thing, there is plenty of space underground to store water. In the Central Valley alone, unused aquifer space where water has been drained by pumping could hold more than three times the total capacity of the state's surface reservoirs, Fogg said.

He said California is on the cusp of more dedicated efforts to replenish water reserves that have long been largely out of sight and out of mind.

“It's important that whenever you have these wet winters, you maximize the potential benefit to recharge,” he said. “Do we maximize it? “We didn’t come close to maximizing what could have been done.”