As associate dean for diversity and inclusion at USC, Dr. Althea Alexander spent time speaking in high school classrooms across the United States, searching for undeveloped talents among Black and Latino students in hopes of guiding them into the medical field.

She mentored minority medical students and sought to improve the school’s efforts to recruit diverse students. Her work, which spanned five decades, paid off tenfold: It influenced the career paths of hundreds of people who would go on to become medical school deans, CEOs and even California’s chief health officer.

Alexander, 89, died July 17 after suffering a brain hemorrhage, according to her daughter, Kim Alexander-Brettler. Her mother forged deep and lasting relationships driven by a passion for civil rights and a sincerity in helping young people improve their lot and that of their communities, Alexander-Brettler said.

“It’s not something she had to practice,” Alexander-Brettler said. “It came from her soul. Giving was very natural to her.”

Alexander came to USC in 1968 and became the first Black woman to be a faculty member. At the time, there was one Black and one Latino medical student enrolled. Alexander sought to change that. USC estimates that by her retirement in 2019, she had touched the lives of at least 800 minority students at the Keck School of Medicine.

In 1969, she became the first dean of Minority Affairs, which would later become the Office of Diversity and Inclusion. In 1992, she told The Times that she believed students of color were never told they had the intelligence, ability or sensitivity to become doctors, and that she wanted to instill that in them as early as possible.

He spoke at high schools and encouraged students to keep in touch. He promised students and their families that if they worked hard, he would help them as best he could to find them a place in medical school.

“We need to train young people to contribute to society,” she told The Times. “If someone gave us a grant to start kindergarten, I would do it.”

Among them was Dr. Diana E. Ramos, who was a high school student heading to USC for her undergraduate studies when she met Althea and her husband, Fredric. At an annual checkup, Ramos met a nurse who introduced her to his boss, Fredric, after learning that she wanted to be a doctor. He introduced her to his wife, an assistant dean at USC’s medical school, and from then on, Althea became a guiding force for Ramos, who was born in the Midwest and was the first in her family to go to college. Ramos graduated from USC’s medical school in 1994.

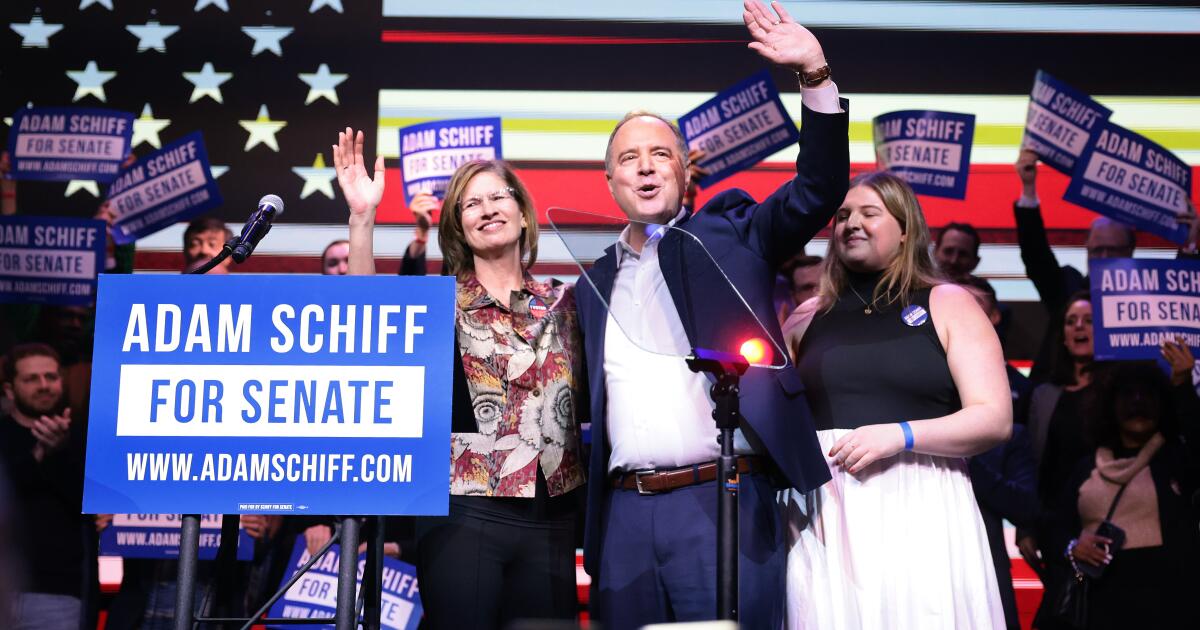

“Whenever I wanted to give up or just needed a little pep talk, she was always there,” said Ramos, who became California’s surgeon general in 2022. When Ramos came into office with lingering feelings of inadequacy, Alexander dispelled those doubts, telling her she was up for the job. “Of course,” her mentor replied. “Why not you?”

At USC, Alexander pushed for admissions to consider nontraditional experiences in addition to grades and test scores, such as an applicant’s work and family history. She and her family hosted dozens of students, often for months at a time, in their home. Alexander helped others pay rent and bought cars for those who couldn’t afford them so they could attend school, Alexander-Brettler said.

Alexander also exerted a national and international influence, as many of USC's students continued their studies on the other side of the country. At a memorial service held Saturday, where alumni shared stories about the impact he had on their lives, speakers recounted how Alexander encouraged them to come to the U.S. from China to further their medical education.

She was not shy about speaking out about racism in the medical field. She previously told The Times about a time when she went to Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center to seek help after breaking her arm. A white resident treating her told her to “hold your arm like you usually hold your beer can on Saturday nights.”

“What are you talking about?” she asked. “Do you think I’m a welfare mother?”

She told the students that they would surely face the same problems.

“This is not a utopia,” Alexander said. “You are what you are… You can’t die on every hill here. If someone makes a racist comment in class, you can’t spend all your energy on that. Be firm and accept it. Say, ‘I don’t like that.’ Then move on.”

She shared a passion for civil rights advocacy, joining protesters during the East Los Angeles riots in 1970, and had a United Farm Workers flag hanging in her office signed by Cesar Chavez.

Alexander had known her husband, Fredric Eugene, since they were children because their parents were union organizers. But in 1959, a young civil rights leader named Martin Luther King Jr. reintroduced them. Fredric and Althea were married at the Unitarian Church in downtown Los Angeles. Fredric died in 2009.

Althea Alexander was born on March 16, 1935, in Berkeley. In addition to her daughter, she is survived by her son, Sean Alexander, and granddaughters Danielle and Lauren Brettler.

Alexander loved music and made a habit of attending live shows. Alexander-Brettler recalled a Prince concert at the Forum where she begged her mother to leave as midnight approached because she had to work the next day. But Alexander insisted they stay for Prince’s four-song encore, dancing the whole time. To close out Saturday’s memorial service, the USC marching band performed.

“It was the icing on the cake,” Alexander-Brettler said. “In the end, we had a lot of fun.”

Alexander's legacy lives on: In 1997, a USC alumna created the Althea Alexander Scholarship Fund to support minority medical students. A group of students created the Althea and Fredric Alexander Student Support Fund to financially support the professional development of medical students, where donations can be made in her memory.