The defendant named in the federal lawsuit was California Secretary of State Shirley Weber, but there was never any doubt that the target was Donald J. Trump.

For a time, as the legal maneuvers progressed through the fall, it looked like Los Angeles might be in for another of its celebrated courtroom dramas, in this case a constitutional showdown pitting a colorful civil rights lawyer against a volcanic former president in the courtroom of a court. He is a judge known for his ardent judicial talent.

The case sought an order barring Weber from placing the Republican presidential front-runner on the California ballot, based on the insurrection clause of the 14th Amendment.

It was also intended to be a trap. If Trump's legal team takes the bait and joins the case, then the former president could be forced to face questioning under oath about his role in the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol.

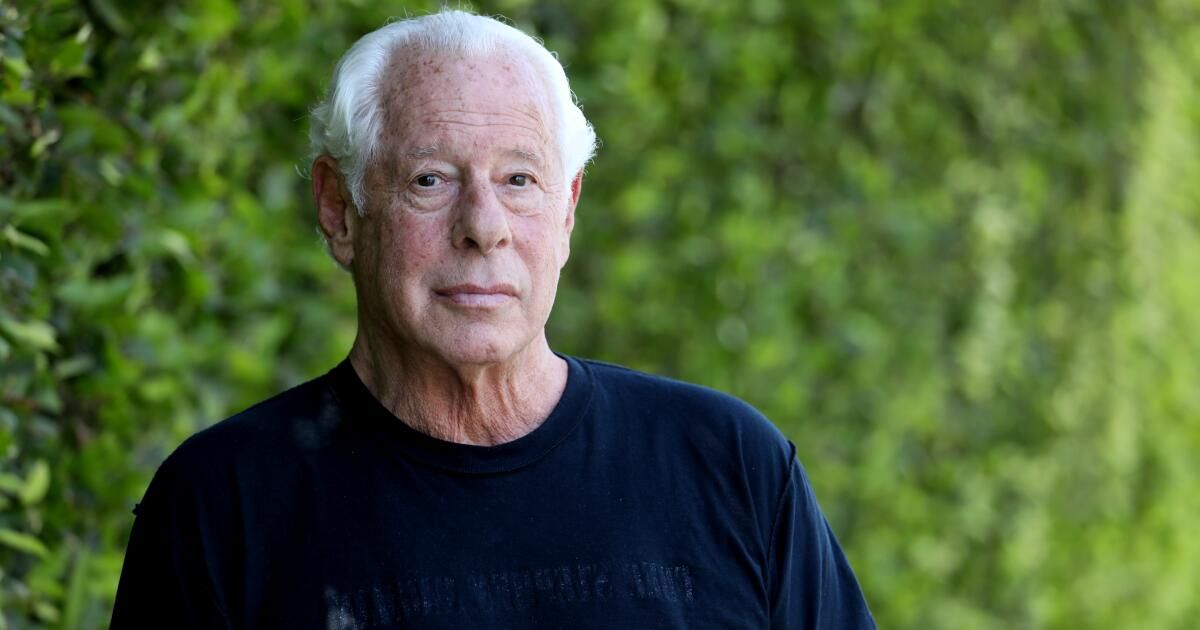

At least that was the theory of Stephen Yagman, a lawyer admired and vilified in local lore for his history of taking down sacred cows.

Over two decades, Yagman broke legal ground in cases against the Los Angeles Police Department and the United States government, establishing that LAPD officers and their leaders can be held personally responsible for violations of civil rights and that prisoners at the Guantanamo Bay detention center had a right to due process. He then suffered an ignominious fall with a federal conviction in 2007 for tax evasion and bankruptcy fraud. At age 70, more than a decade after serving 29 months in prison, Yagman regained his law license and resumed the fight for indigent victims of government abuses.

U.S. District Judge David O. Carter, a figure no less colorful than Yagman, has earned a reputation for judicial unorthodoxy that borders on heavy-handedness. He has taken Skid Row to trial and called mayors and supervisors to account for their ineffective responses to homelessness. In two cases that were active at the time, Carter was pressuring Los Angeles County officials to obtain a commitment for thousands of mental health beds and rebuffing efforts by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to sidestep a lawsuit over housing for veterans. .

More specifically in the Yagman case, Carter had found in a 2022 ruling that stripped Trump's legal advisor, John Eastman, of attorney-client privilege that they “most likely would not” have attempted to illegally obstruct Congress, calling it of “a coup in search of a legal theory.”

Would Carter, who drew the Yagman case because it was related to the previous one, follow that reasoning? Yagman hoped so.

When Trump's lawyers took the bait and asked Carter to intervene, Yagman was practically foaming with anticipation.

“This court, here and now, has a unique opportunity to prevent a truly deranged and dangerous fool, Donald Trump, who perpetrated an assault on American democracy, from becoming president of the United States again,” he wrote in a motion, noting that Trump “has recklessly (for him) intervened to become a defendant in the present action.”

He reinforced his ever-eccentric legal jargon with a literary allusion that invoked both Socrates and the Rolling Stones.

“Trump is a vile man. He has no virtue whatsoever,” Yagman wrote, adding a long footnote about the Greek philosopher's concept of civic virtue.

“And contrary to what Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones sings… Trump, as the current incarnation of the devil… deserves no sympathy…”

But it was in vain. Not once, but twice in the months that followed, Trump's lawyers raised legal technicalities to shoot down Yagman's fiery rhetoric.

The first was based on position, a slippery legal concept that means something like skin in the game.

Yagman's case made the tortuous argument that his client, a Republican voter who planned to vote for Trump, would be disenfranchised if, after the March primary in California, Trump was declared ineligible to be president.

Carter dismissed the case in November, finding his client lacked standing because “the harm he alleges is too widespread.”

Yagman had a backup strategy: an amended lawsuit that changed his case to a class-action lawsuit representing all Republican voters and named Trump himself as a defendant on a novel theory of negligent infliction of emotional distress.

His clients, he argued, were “direct victims of Trump's acts in creating and participating in the insurrection,” both on January 6 and in the “countless viewings of those acts on television, radio, and numerous publications…”

Upon reconsideration, Carter set a hearing for January 8. But over the holidays, Trump's lawyers convinced the judge that the hearing was not necessary. In a Dec. 22 filing, Shawn E. Cowles of the Dhillon Law Group gave eight reasons why the case was without merit, from presidential immunity and First Amendment protection to “reasons to doubt the veracity of the plaintiff's claim.” that he is a registered Republican.” voter in Los Angeles County.”

The argument that prevailed for the former president was based on the statute of limitations. Ignoring Yagman's claim that the injury recurred every time images from January 6 appeared on television, radio or print publications, Carter ruled that the case was time-barred based on California's two-year distress statute. emotional due to negligence.

Yagman, whose past victories included establishing that lawyers cannot be disciplined for making derogatory comments about their judges, showed unusual magnanimity in defeat.

Carter, he said, is a good judge and a decent human being.

“I'm quite happy with him because it's him,” he told The Times. “Part of me is very sorry that this is gone, I really wanted to depose Trump. But I'm ashamed of that because it would be just me playing. “I wouldn’t get anything out of it except laughs.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this story.